Attaining considerable influence in Afghanistan is tied to Pakistan’s economic interests in the region.

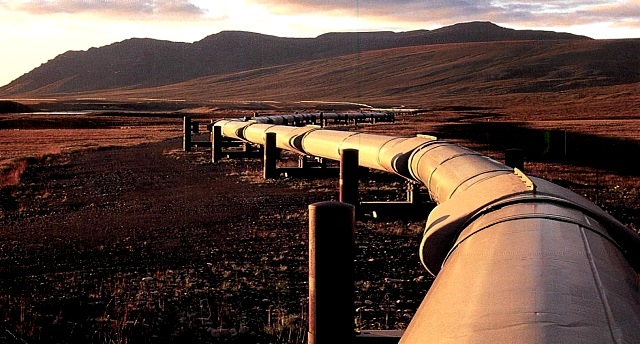

Economics plays an essential role in defining the geopolitical pursuits of the nation-states. In recent years, the Central Asian abundant energy resources, largely untapped, have triggered a race amongst the big powers for gas and oil pipelines in and around the region. In Afghanistan the ‘new great game’ or sometimes called ‘pipeline diplomacy’ regarding the control of energy resources in Central Asia and its routes is shaping up.

Pakistan’s interest in Central Asia sharply increased after the Soviet Union collapse – as it perceived a strategic opportunity there. General Naseerullah Babar, who was central in Pakistan’s attempts to navigate these newly available potential economic opportunities, while negating the military dimension of ‘strategic depth’, said in an interview ‘the talk about strategic depth is nonsense…. We realized that Afghanistan is a perfect corridor for goods from Central Asia. Those countries needed an Asian outlet, especially for oil and gas. We wanted to take advantage of that. Pakistan’s geo-economic significance stems from its position at the junction of “three Asia’s” – West, Central, and South. Moreover, Pakistan and Afghanistan’s geostrategic location between the energy loaded economies of the Middle East and Central Asia, and the energy keen growing economies of India and China naturally trigger some great potential drivers in economic development in both Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Gwadar port, which is on the cusp of South, West and Central Asia, is important in this context. Pakistan’s land mass and Gwadar port are the most suitable gateways to connect energy-hungry India and China, and arguably the naturally available routes to extract oil and gas from Central Asia. The project of Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline, if materialized, would go through Afghanistan and Pakistan before reaching India or China, if it joins in future. Historically, instability in Afghanistan and hostile relations between Pakistan and India has kept India reluctant from going through with this project.

While there is the potential of large economic dividends, there is also some great deal of friction around competing energy supply routes. On the regional level, while India and China are potential rivals for control of energy resources in Central Asia, China’s investment in Gwadar port is compelling India to look for other potential alternative routes to avoid Pakistan. Iranian port of ‘Chabahar’ is a part of this India’s calculation. In this context, Pakistan sees itself as a central player in what goes on in Afghanistan in the future. And perhaps, it would be plausible to argue that with India’s fast-growing economy, which is in dire need of energy resources, Pakistan might be interested in spoiling India’s economic plans by choking it in Afghanistan, the only suitable route. Perhaps, by doing this Pakistan might be looking for some concessions in the Kashmir dispute, which seems impossible. Some have argued that ‘Afghanistan is no longer a corner where nodes of terrorist networks can be hidden. It is a strategically situated route for the transport of Central Asian oil’ and a place of strategic importance for the regional players.

In the post 9/11 milieu Pakistan has lost its strategic mileage in Afghanistan, while India has increased its influence. In this context, some have argued that ‘instability in Afghanistan serves Pakistan’s interests in making it more attractive to key states and major energy companies alike, and it is more likely that they would favor energy routes that pass through Pakistan.’ In the similar vein, some have argued that Pakistan may now have a good strategic reason to maintain a porous border with Afghanistan rather than to press for the recognition of the Durand line as an international frontier that would constrain Pakistan’s scope for interference in Afghanistan Affairs. Arguably from this perspective, Pakistan not only hopes to attain deep space in Afghanistan but also aims to stretch it down to Central Asia.

From Pakistan’s perspective, Afghanistan is a space that Pakistan seeks to control, or at least to decisively influence, as a guarantor of its vital strategic interests. Moreover, this underlying economic competition helps us understand Pakistan’s internal security dilemmas and external threats and how and why Pakistan sees Afghanistan important in its overall security calculation. On the whole, Pakistan seeks a strong hand in Afghanistan, in order to exclude or minimize Indian influence, to ensure Afghanistan doesn’t contest its border with Pakistan and to ensure Afghanistan (and India) doesn’t succeed in its secessionist movements, which might lead to the loss of further Pakistani territory, or perhaps even imperil the state of Pakistan itself. Moreover, an understanding of these issues provides insights into Pakistani actions over recent decades and into Pakistan’s choice of partners as it has sought to reach inside Afghanistan.

Nevertheless, the politics of growing regional pipeline diplomacy and global power politics in Afghanistan will shape the future of geopolitics not only in South Asia but also in West and Central Asia and Pakistan sees it a vital interest.

This article originally appeared on www.pakistantoday.com.pk on February 11, 2018. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.