One of Afghanistan’s most intrepid and long-term observers in the region is Canadian journalist Kathy Gannon of the Associated Press. In April, 2014, she was severely injured in an attack against her vehicle while covering the war with Geneva-based AP Pulitzer prize winning photographer, Anja Niedringhaus, who was mortally wounded. Here Gannon shares her thoughts on covering this never-ending war from her base in the Pakistani capital of Islamabad.

Focus on Afghanistan: 40 years of war.

This article is part of Global Geneva’s special series exploring 40 years of war in Afghanistan. It is scheduled to be published in our November 2018-January 2019 print & e-edition.

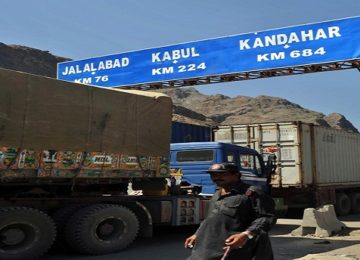

It’s been more than 30 years since I first came to Afghanistan. Then, like now, Afghanistan was at war. The Soviets were the invaders then, and the mujahideen, or Islamic holy warriors, were backed by the United States and heralded as freedom fighters by U.S. President Ronald Reagan.

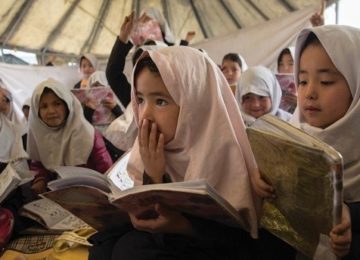

At the time, the University of Nebraska had devised a curriculum to teach Afghan refugee children in camps in northwest Pakistan the English-language alphabet. It went like this: ‘I’ is for Infidel, ‘J’ is for jihad and ‘K’ is for Kalashnikov — all terms used in the battle to fight the godless communists, who had invaded their homeland. Mathematics was little different. It was taught with problem-solving questions such as: If you have 20 communists and you kill 12 Communists, how many Communists do you have left?

That was then.

The mujahideen of the 1980s are today both friend and foe

Today the United States and NATO are often referred to as invaders. Those same mujahideen of the 1980s are today both friend and foe. Some are now Taliban, the enemy, and some are mujahideen-cum-warlords-cum-politicians, supposedly friends, who either influence or are members of the present-day U.S.-supported government in Kabul.

Over the past four decades, Afghans have lived through successive governments, all of whom who have come to power through violence. The Russian-dominated Red Army invaded in 1979 claiming to be invited to protect the pro-Moscow government of Babrak Karmal. Just 10 years later, unable to defeat the U.S.-backed guerrillas, the Russians negotiated their departure, primarily through talks initiated by the United Nations and International Committee of the Red Cross. It now appears that far more than the official figures of 15,000 to 25,000 Soviets may have died during their decade long intervention. (As with many statistics in Afghanistan, reliable figures are often difficult to come by).

Kabul’s Communist PDPA (People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan) government hung on for another three years, until Reagan’s freedom fighters took power. The names of those mujahed leaders, who were installed in Kabul, will sound familiar to anyone following today’s Afghanistan. They were Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Hamid Karzai, Abdur Rasool Sayyaf, Ismail Khan, Atta Mohammad, Rashid Dostum… The list goes on.

Bin Laden: Brought back by a member of today’s Afghan government

At the time they came to Kabul, they had promised to be unified but instead they spent the next four years bitterly fighting each other. More than 50,000 Afghan civilians died during their rule, while whole swathes of the capital Kabul were reduced to rubble. Corruption was overwhelming. The mujahideen-cum-warlords had carved Afghanistan into personal fiefdoms.

It was them – and not the Taliban – who had brought Osama bin Laden back to Afghanistan. During the 1980s, Bin Laden had operated out of Peshawar, first as a supporter of humanitarian action, then a fund-raiser and coordinator for Arab and other foreign jihadists. Bin Laden left when it was clear that he and his ‘Arabi’ were no longer welcome.

Afghan fundamentalist Abdur Rasool Sayyaf’s men, however, went to Sudan to invite bin Laden back to Afghanistan. Operating out of Khartoum, Bin Laden had become a thorn in the side of the Americans, who warned the Sudanese government against harbouring him. Today, Sayyaf, who also inspired southeast Asia’s Abu Sayyaf terrorist group, is a powerful player in the present-day U.S.-backed government in Kabul.

Also of note is the fact that the terrorist training camps, which operated during the Taliban, were a legacy of the 1980’s anti-communist war. These same camps flourished during the four years that the mujahed government was in power. The Taliban inherited them.

Post-2001 Afghanistan: the same thing all over again

The Taliban, many of whom were former Soviet War era insurgents, were the next to rule Afghanistan. They came together out of a frustration with the runaway corruption of the day and the ferocious infighting among the ruling mujahed groups. Their movement gained momentum. When the Taliban eventually took power in 1996, they ruled with an iron fist. They imposed a radical interpretation of Islam that denied girls education, established an unforgiving judicial system that often resulted in limbs amputated for stealing, while also disarming militias and ending drug production.

Then came 2001 and the cycle began all over again.

The mujahideen-cum-Taliban were driven out by U.S. and NATO armies. It was November 13, 2001, when the Taliban finally fled Kabul. I was in Afghanistan that day, having returned to Kabul three weeks earlier on October 23, the only foreign journalist allowed back into Afghanistan by the Taliban. Afghans were jubilant at the departure of the Taliban. They had lived through successive governments and with arrival of each new regime came the hope that – perhaps – this one would (finally) be better than the last.

This time – as before – was no different.

Their hopes soared, their expectations were unrealistic, but with the world at their side, Afghans were sure this time there would be a new future of peace and prosperity. They were wrong.

The West in Afghanistan: Expecting a different result by repeating the same mistakes

It’s now been 17 years since the terrorist attacks in the United States sent the U.S. military and NATO to Afghanistan as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. At peak strength, 42 countries had a combined military force of 150,000 soldiers in Afghanistan. But the U.S., NATO and the United Nations ignored history and chose to continue to do the same thing again and again, somehow expecting a different result.

Many of the same mujahideen-cum-warlords, who had ruled before the Taliban and the rise of this new Islamic movement, were returned to power in Kabul post-2001. In 2014 the United States cobbled together a so-called Unity Government forcing a power-sharing agreement on Afghanistan’s leaders. As in the past, unity eluded them. Instead, their rule, which continues today, has been marked by bitter bickering and widening fissures along ethnic lines. The same thing had happened during the 1980s when both Washington and Islamabad sought to impose their own visions on what the Afghan resistance should be about.

Afghanistan: a disillusioned people and country

Today, in the fall of 2018, the country remarkably resembles the Afghanistan of 1992 to 1996. Haroon Mir, an analyst in Kabul, says the only reason rockets are not raining down on the country’s capital today is because of the presence of foreign forces in Afghanistan.

Afghans are disillusioned. They say the money that flooded Afghanistan after 2001 fed the country’s corrupt. Poppy production is at an all-time high with government officials enriching themselves as much as the insurgents. Violent attacks are relentless. The Taliban are stronger. A fresh hell has been inflicted on the country by an Islamic State affiliate and, once again, all of Afghanistan’s neighbours – Pakistan, Iran, China, India and Russia – have their hand in the game.

But the greatest tragedy of today’s Afghanistan is the dwindling hope of so many Afghans that something better is possible. For numerous Afghans who never left their homeland, not when the Communists came, nor the mujahideen, nor the Taliban, are now trying to find a way out.

Many are afraid. They look around at their impoverished country devastated by violence and graft. They wonder at how it happened despite the involvement of a superpower, dozens of other countries and the world’s best militaries.

A friend of mine who worked and stayed in his homeland through each of these successive regimes always insisted: it will get better. He was forever optimistic; that is, until an attack on the American University in Kabul. He waited until 4 a.m. to learn whether his son, who was inside, was alive or dead. As he stood outside, watching bodies being carried out, the injured helped to safety, he swore that if his son lived he would send his family away. His son survived and the family is now in Turkey.

One day my friend, who still lives and works in Kabul to support his expatriated family, hopes to bring them home. But this may only remain an unconvinced assertion. “I was always optimistic,” he told me later. “But no more.”

Reporting in Afghanistan: A privilege

When I was shot in Afghanistan in 2014 and my friend and colleague, Anja Niedringhaus, was killed people asked: “How can you go back?”

My first thought was: “How can I not?”

Seven bullets shattered my upper body but even as I healed I understood that war – and in my case, war injury – does not define a nation or a person. The person who shot us was representative of only himself, not Afghanistan. The millions of Afghans who have struggled through decades of war, found the courage to endure loss and suffering. They are the ones who define this extraordinary country. For me, they’re also the ones whose voices go unheard.

What we do when we tell their stories is we reveal the real awe-inspiring courage of those who choose to speak out, who live with chaos and tragedy, and who soldier on because they must.

What worried me the most when I returned to work after the attack was that I would look at people differently. I was afraid that fear would cloud my perception. I was afraid that the real joy that I had always felt going out into the field would be replaced by this fear. But it hasn’t. If anything I feel stronger than ever that what we – as journalists – do is a privilege.

On a recent visit to Kabul I was sitting on the floor in the home of a mother who had lost her son in an explosion. I watched her kiss and kiss over and over the picture of the lost child and saw in her real courage. It was a courage that enabled her to face life without her child and to know that her other children risked dying, each time they stepped outside the door.

I also often recall something that Sabeen Mahmud, a Pakistani activist, and a woman, who was shot and killed in Karachi three years ago, once said: “Fear is just a line inside your head. You choose on what side of the line you want to be.”

The author Kathy Gannon is a senior correspondent for the Associated Press for Pakistan and Afghanistan based in Islamabad. She has been reporting the region for the AP since 1988.

This article originally appeared on the Global Geneva Website on October 10, 2018. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.