December 06, 2018.

The Taliban today control or influence whole swathes of Afghanistan. Estimates of exactly how much vary, but in the vast majority of Afghanistan’s provinces, control is split between government and insurgency. What that means for local people in terms of services usually provided by a state is the subject of a new research project by AAN. It looks at the delivery of education, health, electricity and telecommunications in six insurgency-affected districts. In this first dispatch, Jelena Bjelica and Kate Clark introduce the series, reviewing previous research, explaining our research methodology and discussing what AAN expects the six case studies will reveal about life under the Taleban.

Service delivery in insurgent-affected areas is a joint research project by the Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) and the United States Institute of Peace (USIP).

The first part of this dispatch focuses on the re-emergence and growth of the Taleban from 2001 onwards. This is followed by an overview of existing research on the Taleban’s delivery of services. Finally, we explain our methodology of research and look ahead to the six case studies.

1. Gradual emergence of parallel systems of governance

The Taleban transition to an ‘insurgent parallel government’

After being ousted from power in 2001, it was only very slowly and locally that the Taleban re-emerged. Their main mission was and still is military – expanding (or re-expanding) territorial control, harrying and trying to push back foreign troops and government forces and using assassinations, bomb attacks and other means to pressure civilians into compliance. At the same time, the Taleban movement has sought to present itself as a government – unfairly ousted from power, but a government nonetheless, one “in absentia,” as Alex Strick van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn in An Enemy We Created(p308) put it. This stance is reflected in the Taleban’s own way of referring to their administration; ever since 1996 when the movement captured Kabul, and up to the present, it calls itself the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA).

The Taleban do not consider themselves a political party and have never provided a ‘policy agenda’, beyond that painted with the roughest of brush strokes, promising a ‘broad-based Islamic government’ (prakh-benseta Islami hukumat) (see AAN analysis here). Indeed, one of the ironies of the movement presenting itself as a government is that its political project is so thinly thought-out, in terms for example, of how the Taleban envisage the relationship between citizen and state, or their policies on education, the economy, the status of women etc. Nevertheless, the fact that the Taleban have come to control territory in recent years has meant that, as in the pre-2001 era, they have had to address some of these ‘policy issues’, in practice. That includes the delivery of services normally associated with a state and the development ‘civilian’ structures dealing with governance.

In the early years of the international military intervention in Afghanistan, the ousted Taleban government “had no real structures or hierarchies, with which to regroup and revive,” commented Strick van Linschoten and Kuehn (An Enemy We Created, p244). According to these authors, in the period between December 2001 and June 2003, the Taleban leadership had not “even a firm position on whether to start an insurgency or to try to have a voice in the new political realities within Afghanistan.” They describe how the structure of and recruitment for the Taleban movement’s military force based on andiwali, a Dari and Pashto word for friendship or comradeship, the ties of mutual loyalty and solidarity forged “through long-standing relations built on family, clan, tribal affiliations, friendship” during the war (andiwali is not restricted to Taleban, of course) (pp246-54 for). AAN’s Thomas Ruttig in his 2010 paper on the Taleban also offers the following insight into the structure of the movement, not limited to their (dominating) military structure:

Today’s Taleban movement is dualistic in nature, both structurally and ideologically. The aspects are interdependent: A vertical organisational structure, in the form of a centralised ‘shadow state’, reflects its supra-tribal and supra-ethnic Islamist ideology, which appears to be ‘nationalistic’ – i.e., it refers to Afghanistan as a nation – at times. At the same time, the movement is characterised by horizontal, network- like structures that reflect its strong roots in the segmented Pashtun tribal society. The movement is a ‘network of networks’.

The first post-2001 Taleban shura, formed in June 2003, that oversaw the launch of the Taleban insurgency under Mullah Omar’s leadership (see AAN reporting here), was “made up of ten members and was responsible for the Taleban political and military’s strategy” (An Enemy We Created, p253). In the period that followed (2003 to 2005), available research shows that the Taleban consolidated and set up structures “to mobilise support in order to expand and popularise an insurgency throughout the Afghanistan” (An Enemy We Created, pp261-3). The one quasi-state service provided by the Taleban from the beginning of the insurgency – and indeed from the earliest days of ‘taleban fronts’ during the anti-Soviet resistance of the 1980s were courts. Post-2001, whenever Taleban insurgents sought to move into an area, they “prioritize[d] setting up alternatives to the state’s judicial system” wrote Carter and Clark in “No Shortcut to Stability: Justice, Politics and Insurgency in Afghanistan”, 2010, pp21-22). Because of the corruption and inefficiency in the government’s judicial system, these became one of the insurgency’s main strengths: “Through their control of the justice systems,” wrote Frazer Hirst (2009), who worked with the British PRT in Helmand and wrote an internal report for DFID, “Support to the Informal Justice Sector in Helmand”, “the Taleban gain a level of control, influence and support which tends to undermine the links between communities and government.” (See also Tariq Osman, “The Resurgence of the Taliban in Kabul, Logar and Wardak”, in Giustozzi (ed), Decoding the New Taliban, pp43–56 and also this 2012 Integrity Watch Afghanistan paper).

In 2006, the Taleban issued their first layha or code of conduct. It laid out “a vision of guerrilla warfare that is not just a fight between armed forces, but a struggle to separate the population from the state and create ‘social’ frontlines” as AAN’s Kate Clark wrote in her 2011 paper, “The Layha: Holding the Taleban to Account”. She described the particularly harsh policies on schools and NGOs:

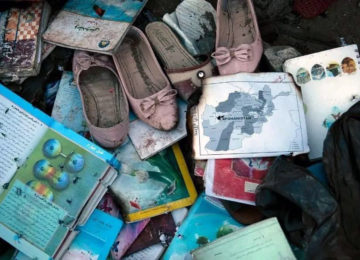

In the 2006 Code, teaching in government schools was deemed illegal and punishments were harsh. Teachers were to be warned and if necessary beaten: ‘. . . if a teacher or mullah continues to instruct contrary to the principles of Islam, the district commander or group leader must kill him’ (2006:25). Education was allowed, but only in a mosque or similar institution, using jihad or Emirate-era textbooks and by someone with religious training. Schools were to be closed and if necessary burned (2006:25). Any contract with an NGO, in exchange for money or materials, had to be authorised at the highest level, by the leadership shura (2006:8).

In terms of structures, the layha of 2006 mentions only a military commission, and unspecified provincial, district and regional officials. Strick van Linschoten and Kuehn pointed out that, even though the Taleban had been engaged in a campaign to “win over rural Afghans since 2005-2006,” it was not until 2008-2009 “that the provision of services and accountability became more widespread” (p285). They also noted that the system of courts, which had been operational since 2001, “albeit in highly reduced form,” spread from 2007 onwards “to different locations and met more regularly.” This, the authors said, happened parallel to the rolling out of a more responsive complaints system, “whereby inhabitants of rural areas could request investigations into corrupt Taliban commanders or members.” Two new committees, one to handle complaints from commanders and fighters, and another to deal with villagers’ grievances, were set up in 2008 (see here; see also AAN reporting here and here).

However, the real change in governance structure was indicated in the 2009 layha. It laid out a more complex governance structure which, next to military commissions, now included provincial and district commissions, as well as education and trade commissions. The 2009 code (see Clark’s paper for translation of all three layhas) said:

Provincial officials are obliged to establish a commission at the provincial level with no fewer than five members, all of whom should be competent. This commission, with the agreement of the provincial official, should establish similar commissions, also at the district level. Some of the members of both commissions should [usually] be present in their area of work.

In several places in the 2009 layha, provincial and district governors are mentioned in relation to various tasks. The 2009 code does not specify how these governors were to be appointed, or by whom, although it does lay out detailed reporting lines.

The third – and still most recent – layha was published in 2010. It further expanded the quasi-state bodies, adding Commissions for Health, (art 61), Education (art 59) and Companies and NGOs (art 60). Clark writes: “[T]he minimal nature of this will be no surprise to anyone familiar with the Islamic Emirate pre-2001 when, for example, ministers would frequently be away from their desks fighting at the various frontlines.” (See here).

During the same period, the Taleban also changed their already evolving attitude towards education. After they removed an order to attack schools and teachers from their code of conduct in 2009, they also engaged with the Ministry of Education, which decided to re-start negotiations with the Taleban (For more detail on this, see AAN papers here and here).

After 2014, ie in the post-ISAF period, the Taleban have not only expanded their territorial control and dominance (more on which below), they also seem to have consolidated their ‘service delivery’ provisions and system of ‘taxation’.

Most of the various Taleban commissions – on education, health, agriculture, trade and commerce, financial affairs and NGOs – do not themselves provide services. Instead they seek to co-opt the services of government, NGOs and private companies at the local level, by controlling and influencing them. In some cases, they use government money transferred to local Taleban officials and themselves ‘pay’ workers providing services, eg school teachers. (1)

Reports of Taleban parallel governmental structures have come up in the Afghan and international media occasionally, but consistently in recent years. Afghan media, for example, reported in 2017 that Taleban all over Ghazni province were systematically taxing “media outlets, businessmen and common people” and even “Provincial Council members [and] governor house officials,” that the Taleban send electricity bills to customers in Kunduz and extort road tolls from truckers in Zabul. The Taleban were also reported to be building up networks of privately-financed madrassas and mosques in Helmand and Badakhshan. Their courts continue to operate, mediating in land and other conflicts (for example, in Jawzjan). They are also reported as maintaining prisons, for example, in Helmand, imposing changes on the school curriculum (for example, in Logar) and having a say in the hiring and firing of teachers. In Taleban-held areas, the Taleban have been reported using government funding sent to schools operated by the Ministry of Education (see this BBC reportage from Helmand). They also ‘regulate’ mobile network providers and determine at what time of the day they can operate (see this report from Helmand here and from Ghazni here). While the Taleban used the mobile networks in early 2010s to spread propaganda (see this BBC report), there are reports suggesting there a formal policy of taxing mobile service providers has been in place since late 2015 (see this Tolo news). In January 2016, the AFP wrote: “At a secret meeting last month [December 2015] near Quetta, the Taliban’s central leadership formally demanded the tax from representatives of four cellular companies in exchange for not damaging their sites or harming their employees”. The news agency’s sources reported that this “edict was motivated by an Afghan government announcement… that it had amassed a windfall of 78 million Afghani (1.14 USD) within days of imposing an additional ten per cent tax on operators.” The Taleban have started posting videos and statements in which they claim to have organised road building and other infrastructure projects. Another indication of the insurgent group’s reach was a BBC report from January 2018 reporting that Taleban rule in parts of some provinces like Uruzgan was so unchallenged, they could “focus on health, safety and trading standards.” (2)

How many people get Taleban controlled or influenced services?

Defining how much of Afghanistan’s population, territory and districts are under the control or influence of the Afghan government and Taleban is subject to debate (see this AAN analysis of how to measure insecurity and control). Assessments vary, although it is clear that, at the very least, the Taleban influence many people’s lives. Both recent Resolute Support data (published by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction’s, SIGAR in October 2018) and the BBC in January 2018, using different assessment methods, (3) found that, although many more districts were under full government control (18 per cent and 30 per cent respectively) than full Taleban control (2.5 per cent and 4 per cent), the Taleban had a presence in a large number of districts, albeit to varying degrees. Resolute Support found that, in addition to those districts under full insurgent control, 78 per cent more were ‘influenced’ by the government, or were ‘neutral’ or ‘influenced’ by the Taleban. As for the BBC, it found that, again, aside from those where the Taleban were in full control, 66 per cent of other districts had an ‘open Taleban presence’. Note that some analysts feel the US gives too rosy a picture of government control (see this New York Times article quoting data from the FDD’s The Long War Journal. According to SIGAR reports, most Taleban expansion came between November 2015 and November 2016 when the government lost about 15 per cent of the districts it had controlled or influenced.

The Resolute Support metrics quoted by SIGAR which assess governance and taxation give a little more sense of the number of districts where, in at least some areas, the Taleban are likely involved in service delivery. For example, Resolute Support’s categorisation of districts uses the following metric on governance:

- 1. Under insurgent control: No district governor or meaningful presence. Insurgents responsible for governance

- 2. Under insurgent influence: No district governor and limited governance. insurgents active and well supported

- 3. Neutral: No district governor present and limited presence

- 4. Under government influence: District governor present and governance active. Insurgents active but have limited influence

- 5. Under government control: District governor and government control all aspects of governance. Limited insurgent presence.

The Resolute Support, in October 2018, put about 45 per cent of all districts into categories one to three and in those places, one could expect the Taleban to have control or influence over service delivery in at least some areas of the district. Even in category four districts this might be the case. The Resolute Support metric on taxation also suggests that at least some people living in districts categorised one to four will be paying a Taleban ‘tax’. It says “a shadow system” of Taleban taxation is “present in some areas” of category 4 districts; is “effective” and “commonplace” in category 3 districts and; is “dominant” in category 2 districts. In category 1 districts, the local economy is “controlled” by the insurgents. The mirror image of this, of course, and it is worth stressing, is that the government has some influence and control over governance and taxation in districts categorised 2-5.

Many Afghans then, will be having to deal with the Taleban when it comes to services normally provided or regulated by a state and the Taleban will have to be dealing with people’s expectations and demands when it comes to these services. How this works out in practice is the subject of this research. We have chosen six districts as case studies (more on which later) and each will be the subject of a separate dispatch. In this piece, we want to look at what has already been written on this subject and present our methodology for research.

2. Previous research

Insurgent-run service-delivery: a literature review

There are a limited number of publicly available studies that deal with Taleban service delivery provisions and administration. There is a much bigger literature on public service delivery in Afghanistan, generally, and this context is important for understanding what the Taleban do. The Afghan public service sector – especially education and health care – has greatly expanded and improved since 2001, in terms of schools and health services becoming more widespread and available. However, both sectors remain heavily dependent on development aid and aid agencies. For example, health services in Afghanistan are outsourced to 40 national and international NGOs that are mandated with delivering basic health provisions in 31 provinces (in the remaining three provinces, the Ministry of Public Health directly delivers). For an overview of health service delivery in Afghanistan see here. Apart from security, the area that has received most financial support is what could be called ‘social infrastructure’ (ie building schools, roads and hospitals) and accompanying services, primarily education and health care.

As to paying for these services, in 2016, the World Bank described Afghanistan (page, 3) as “unique worldwide in its extraordinary dependence on foreign aid.” Aid, said the Bank “is critical to financing growth, service delivery, and security.” Aid to Afghanistan amounted to around 75 per cent of GDP between 2005 and 2011 and, even though government revenues have increased since then and aid fallen, in 2017, aid still stood at around 45 per cent of GDP. The Washington-based Institute for State Effectiveness suggests a rule of thumb for a functioning, sovereign state that aid should amount to a maximum of 20 per cent of GDP. More than that – and Afghanistan has received far more than the optimum over many years – risks corruption and government mismanagement, says the Institute. (For more analysis of aid, see this AAN reporting from earlier this year)

Public services in Afghanistan have, indeed, been riven with corruption. For example, the 2017 Independent Joint Anti-Corruption Monitoring and Evaluation Committee’s (MEC) report showed that in the education sector corruption has become endemic in the last 10 to 15 years and that malpractice is systemic within the ministry (see AAN reporting here). Another MEC report about corruption in the Ministry of Public Health from June 2016 showed that the Afghanistan’s public health sector also suffers from “deep and endemic corruption problems.” (See also this SIGAR report on corruption in the health sector). This is one aspect of the context within which the Taleban have co-opted government-funded services.

Another contextual issue worth stressing is that, as the two AAN publications on education cited in the last section pointed out, (non-madrassa) education, particularly but not exclusively of girls and women, has been a political football for decades in Afghanistan, used and occasionally enforced by various governments and their backers as a marker of ‘progress’ (eg the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan’s regime between 1978 and 1992, and post-2001 administrations) or attacked by opposition groups and governments and their backers for being a conduit of foreign influence (eg the mujahedin in the 1980s and the Taleban in and outside government). Parallel dynamics have also applied in attitudes towards madrassas and the religious education sector. Attitudes among the general population have also varied, but, particularly after the refugee experience for millions of Afghans in Pakistan and Iran, more people have welcomed or indeed demanded the education of their children than in previous decades. That has included the education of girls, although to a lesser extent. Taleban attitudes towards government schools and the curriculum since they lost power need to be seen in this context.

As to healthcare, this has never been a political issue in the way education has been, (4) as the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) wrote in its study, “The Political Economy of Education and Health Service Delivery In Afghanistan”:

The Taliban opposition never objected to the delivery of health services in principle, mainly because they saw health delivery as less “political” than education and clinics as useful to the Taliban themselves, unlike state schools.

In terms of general reporting on Taleban service delivery, Giustozzi’s 2017 report for Landinfo (an independent body within Norway’s immigration authorities), “Afghanistan: Taliban’s organization and structure”, says that it is limited due to financial constraints, with the exception of the courts and, Giustozzi says, some clinics, which are not co-opted government ones, but the Taleban’s own:

Some of the Taliban leaders seem to think that service delivery is a source of political legitimacy. Due to financial limitations, however, the Taliban delivers only very few services, with the exception of justice. The decision by Haibatullah Akhund in 2016 to open up Taliban clinics to the general population was only implemented in a haphazard way for lack of funding. There have been cases of Taliban taxing the local population for specific projects, such as road building. Taliban-provided education is limited to some hundred madrasas.

Giustozzi further asserts that “the Taliban simply highjack government services, as in the case of education”:

The Taliban impose their own curriculum, textbooks and teachers, while the government continues to pay salaries and all other expenses. The Taliban also stamp NGO and humanitarian agency projects with their seal of approval, often even sending their representatives to the inauguration of projects alongside government officials.

Michael Semple in a 2018 article, “Afghanistan’s Islamic Emirate Returns: Life Under a Resurgent Taliban” scrutinises one district under Taleban dominion, Chapa Dara in Kunar, and shows a mixing of military and civilian aspects of Taleban control. The shadow governor Rahm Dil, says Semple, “adjudicates disputes among civilians while commanding a fighting force of about 50 men.” Moreover, “If a Talib in Chapa Dara arrests someone on suspicion of committing some kind of infraction, for instance, he will always quickly refer back to Rahm Dil for guidance on whether to hold, release or kill the person.” There is also a unit of the Amr bin Maroof, or religious police, in the district who ‘police’ moral crimes and behaviour. The Taliban’s main economic function in Chapa Dara, says Semple, is “maintaining security, thereby allowing businesses to operate safely,” businesses which the Taleban then tax (the ten per cent ushr). Semple also found that:

The Taliban actively involve themselves in the provision of public services, but the actual resources for those services come from elsewhere. In the education sector, the government in Kabul funds schools… the Kabul-based government has more of a presence in the health sector.

Some studies offer an in-depth look at certain aspects or sectors of service delivery. A 2016 study, “Enhancing Access to Education: Challenges and Opportunities in Afghanistan” by Barnett Rubin and Clancy Rudeforth from the Center on International Cooperation (CIC) at New York University found (5) that “Taleban policies and practices with respect to education remain inconsistent,” but it pointed out that:

The Taliban have released several statements in support of education in recent years[6], and several teachers working in Taliban-influenced areas have described a relative improvement in education delivery since 2011. This comes partly as a result of Taliban monitoring of teacher attendance. […] And yet, in districts under Taliban control, availability and quality of education remain poor. Restrictions on girls’ education are still widespread. Direct attacks against educators and schools are no longer systematic, but they still happen. The Taliban sometimes use school closures as a bargaining tactic to exert control over the education sector, or as leverage over unrelated issues.

The CIC research also suggested that:

[L]ocal Taliban are more likely to support education if they perceive control of the curriculum, distribution of MoE funds, teacher hiring and placement, monitoring of attendance and performance and health and security arrangements at and around maktabs[non-religious schools] or designated learning spaces. This perceived control is often the result of local political settlements between Taliban and education providers, agreed with dialogue and mediation assistance from elders and ulama.

AREUs’ 2016 study on education and health (quoted earlier) which focused on three provinces, Wardak, Badghis and Balkh, found:

[T]he primary objective of the insurgents is not, however, to close schools, but rather to co-opt them. The Taliban try to assert control over schools through deals with local MoE officials: the schools stay open, but changes are made to the curriculum, with the Taliban being allowed to inspect the schools regularly. The Taliban claim that in Wardak, such deals extend to 17 percent of all schools, while in Badghis, the rate is 13 percent. As of 2013, no such deals had been implemented in Balkh.

As to health services, although the Taleban do not see this sector as politically controversial, AREU says they have

…gradually evolved a policy of asserting control over the sector through their own registration system. NGOs and government clinics have been asked to treat the Taliban and allow facility inspections to ensure that they were not being used for “spying” purposes; in the event of a refusal, violence and bans have sometimes occurred.

The most recent studies, like the 2018 Oversees Development Institute’s study, “Life Under the Taliban Shadow Government” by Ashley Jackson, offer a broad-stroke assessment of service delivery in the Taleban controlled area. The ODI research, which was carried out across a number of districts in Wardak, Kunduz, Laghman, Logar, Helmand, Kandahar, Uruzgan and Zabul provinces, concludes that “Taliban governance does not supplant the Afghan government but co-opts and augments it, resulting in a hybrid service delivery arrangement.” On education, the study said that the Taliban “have capitalised on the fact that so many schools suffer from such high levels of corruption and dysfunction (teachers do not show up, textbooks are sold rather than distributed),” and that the majority of interviewees said that they “felt that the Taliban had improved the running of the government education system.” The Taleban are often in direct contact with the NGOs that provide health services, the ODI research found, adding that this contact is “usually initiated by the Taliban when there is a specific issue to discuss.”

The ODI research also offers some insight on mobile service and electricity supply. The research said that “the Taliban claim to exert control over at least a quarter of the mobile grid,” and also that “in at least seven provinces the Taliban are collecting on the vast majority of electricity bills.” This needs to be put into context. Of the 89 per cent of households in Afghanistan who reported to the 2013-2014 Living Conditions Survey that they had some kind of access to electricity, only 29.7 per cent received their power from the grid. It is not clear from the ODI research in which districts the Taleban are collecting these electricity bills. The study also said:

Private cell phone companies appear to routinely pay taxes, which they often negotiate locally and in Dubai. They are also subject to Taliban regulation of their services. This entails dictating when cell phone services should be provided, with the most common stipulation being that they be shut down after dark… The government mobile provider, Salam, is banned in Taliban areas, and the Taliban check mobile phones for Salam sim cards. Being caught with one will likely result in the card being destroyed and the owner being beaten.

All of these studies point out that, although inconsistent and arbitrarily provided, service-delivery is a vital part of Taleban governance in areas under their control. (7) In order to understand how these services are delivered in different parts of country, AAN decided to conduct a series of six case study, informed by the literature reviewed in the previous sections and using a methodology outlined below.

How we did the research: methodology

For this series of case studies, AAN combined two research methods: desk research and semi-structured interviews with key informants.

As samples, AAN chose districts from six provinces that represent five key regions of the country – the northeast, southeast, east, south and west and which and under varying levels of influence by the insurgency. The selection criteria have been further guided by AAN’s in-house resources and access in terms of the contacts and familiarity of AAN researchers with specific districts. That is, AAN sought to identify districts from different parts of Afghanistan in which the insurgency has between some and considerable influence, but that remain accessible enough so that a high standard of qualitative research can be conducted. Based on this, AAN selected the following provinces and districts for this study:

- In the north: Kunduz province; Dasht-e Archi district

- In the southeast: Ghazni province; Andar district

- In the south: Helmand province; Nad-e Ali district

- In the west: Herat province; Obeh district

- In the east: Nangrahar province; Achin district

- In the central highlands: Maidan Wardak; Jalrez district

From the desk research, AAN developed a profile for each district after consulting various government and non-government sources, including interviewing people working in government line ministries and NGOs providing services. The aim here was to get basic information about the district (size, type of land and agriculture, demographics, transport links senior government and Taleban officials) and service deliveries (such as the number and type of schools and medical facilities, mobile phone providers and sources of electricity, number and level of access of teachers and medical staff, and for public service goods, such as school books and medical supplies).

After drawing up the profiles, AAN conducted 10 in-depth interviewswith key informants in each district, based on a semi-structured questionnaire, itself developed following a review of the relevant literature. To get information that reflects the complexities of governance in Taleban-controlled areas, key informants from communities under study were carefully selected; they included tribal elders, respected individuals in the districts, civil society activists and journalists. They were interviewed either in person or over the phone, using the semi-structured questionnaire, which was divided into five thematic areas:

- Basic information about the district

- Education services

- Health services

- Telecommunication and electricity services

- Other services available

The aim then was to triangulate the desk-study data (to the best extent possible, given limitations of access and of information) about government services with the qualitative descriptions of perceptions and experiences collected through the semi-structured interviews to produce each case study in this series.

Looking ahead to the case studies

As this dispatch was published, the results of our research were still coming in. Nonetheless, from the first two finalised case studies (Obeh district of Herat province and Dasht-e Archi of Kunduz province), which will be published this month, we are already getting interesting empirical evidence about what AAN’s Said Reza Kazemi describes as an “unstable, hybrid form of governance.” This not only concerns the methods and extent of the Taleban’s co-option of services, but also how local populations negotiate or try to find ways around Taleban requirements. For example, after the Taleban banned men from teaching girls in Obeh, in those areas where there were no women teachers, local people found female high school graduates to teach and so kept girls schools open. AAN research is also pointing to a sort of pragmatism on the part of some government officials in dealing with the Taleban to keep services running. Again, in Obeh, local education officials have sought to place teachers ‘acceptable’ to the Taleban in areas under their control. From the two finalised case studies, a pattern appears to be emerging, as well, of both government officials and Taleban extracting ‘rent’ from some but not all services (in the form of taking bribes, pocketing the bogus salaries of non-existent workers and ‘taxation’).

With so many Afghans now living in areas under Taleban influence or control, the affect of this on the education of children, the health of people and their access to electricity and to social media and national broadcasters or just the phone are all important topics of research. Our six district case studies are aimed at helping understand these dynamics. We hope the granular nature of these studies will clarify how coherent Taleban policy on the various services is. We also hope they will help unpick local particularities, pointing to what drives the differences in how the Taleban control services to those living under their dominion.

Edited by Thomas Ruttig and Sari Kouvo

(1) The Taleban’s website has a list of working commissions and their contact details. AAN contacted the Taleban commissions for agriculture, the disabled, power distribution and education using the numbers listed on their website to ask about the policy they are implementing and in how many districts in the country they are implementing this policy. However, most of the phone numbers were not working or were answered by common people. For example, of the two numbers listed for the education commission, one was not working, and the other number was answered by a woman, not related to the Taleban. The agriculture commission’s contact was answered by a person speaking Dari and sitting in a very busy place, judging by the background noise. The person who answered the phone for the department for power distribution told AAN that they help NGOs and the Ministry of Energy and Water to collect taxes.

(2) In Uruzgan, the Taleban were able to temporarily close down 46 of the province’s 49 clinics in summer 2017, reportedly after their demand for special treatment for their wounded fighters was turned down.

(3) SIGAR currently deploys Resolute Support criteria to categorise the ‘stability’ of districts, with five categories: under insurgent control, under insurgent influence, neutral, under government influence and under government control. This method considers such issues as who governs, who gets taxes, who controls infrastructure and who controls ‘messaging’ – see page 5 of this report for further explanation).

The BBC split districts into those where the government at least controlled the district centre (under government control) and those which it did not (under Taleban control). Of those controlled by the government, it split them into three categories: those with a ‘high active and open Taleban presence’ (defined as suffering at least two attacks a week during the research period; a ‘medium open Taleban presence’ (attacked at least three times a month) and; a ‘low open Taleban presence’ (attacked once in three months). (This excluded attacks on urban centres which the BBC dealt with separately.)

(4) This was why, when the Islamic State in Khorasan Province (ISKP) ordered the closure of government clinics (and schools) in Nangrahar and threatened health workers there in 2015, it was so shocking. As David Mansfield put it in the AREU February 2016 publication, “The Devil is in the Details: Nangarhar’s Continued Decline into Insurgency, Violence and Widespread Drug Production” ISKP breached the normal Afghan ‘rules of war’:

… Daesh are understood [by Nangarharis] to have broken local mores with their brutality and their failure to recognise the needs of the local population, including with the closure of schools and clinics, and their prohibition of the production and trade of opium and marijuana.

See also AAN reporting here.

(5) For the Taleban’s past education policies, see also “Schools on the Frontline: The struggle over education in the Afghan wars” by Thomas Ruttig, a chapter in a forthcoming book: Fereschta Sahrai, Uwe H Bittlingmayer et al (eds) Education and Development in Afghanistan: Challenges & Prospects,Global Studies, Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld:

When the Taleban swept to power in an area, their commanders often used to replicate Bacha-ye Saqao’s approach from 1929: they almost automatically closed down schools, particularly girls’ schools. After they captured Kabul in 1996, they shut down 63 schools within three months there alone, “affecting 103,000 girls, 148,000 boys and 11,200 teachers, of whom 7,800 were women”; they also temporarily shut down Kabul University. In some areas, girl schools were altered into boy schools (Najimi 1997: 6). Even if they did not close the schools, the ban for women teachers to work also affected them, as they had also taught at boy schools. “By December 1998, UNICEF reported that the country’s educational system was in a state of total collapse with nine in ten girls and two in three boys not enrolled in school” (Rashid 2000: 108). It further estimated that at that point “only 4 to 5 per cent of primary aged children g[o]t a broad based schooling, and for secondary and higher education the picture is even bleaker” (Clark 2000).

It is worth pointing out, however, that the Taleban policy on banning girls’ education was never as complete as usually reported. In 2000, AAN’s Kate Clark visited a functioning school in Kabul city, with classrooms and blackboards, run by Afghan women, and one in a village in Kabul province, run by Care International. The Taleban were turning a blind eye to such endeavours, although everyone was aware that they could close down such schools in an instant. Schooling for young girls was – then as now – much more possible than for teenage girls.

(6) The CIC report quotes a statement released by the Taleban’s Commission for Training, Learning and Higher Education on 13 January 2016, saying it “reiterated support for ‘modern education’ [as the Taleban term non-madrassa schooling] based on the following principles”:

- Education, teaching, learning and studying the religion [are] basic human needs.

- The Taliban in accordance with its comprehensive policy has established a Commission [to] … pursue, implement and advance its education policy.

- The Commission seeks growth to all educational sectors inside and outside the country, be they Islamic such as religious Madaris, Dar-ul-Hifaz, village level Madaris, up to legal Islamic expertise; or be they modern primary, intermediate and high schools, universities or specialist and higher education institutions.

- For the development of these institutions, if any countryman seeks to build a private institution, the Commission will welcome their effort and lend all necessary help available.

- To raise the education level and standardize these institutions the Commission will welcome and gladly accept the views, advice and constructive proposals of religious scholars, teachers and specialists in religious and modern sciences.

- The Commission seeks … to encourage and motivate the sons of this nation towards educational institutions and to give special attention to creating opportunities for educational facilities at village level.

- The Commission has provincial level and district level officials who will execute all educational plans and programs in their respected areas. All the respected countrymen will be able to gain access to them regarding affairs of education.

(7) For further reading on the Taleban movement and how it has evolved over time, see:

Willam Maley (ed) Fundamentalism Reborn? Afghanistan and the Taliban, London, C Hurst & Co Publishers 1998

Peter Marsden, The Taliban: War, Religion and the New Order in Afghanistan, London, Zed Books 2002

Antonio Giustozzi (ed) Decoding the New Taliban: Insights from the Afghan Field, London, C Hurst Co Publishers 2009

Ahmed Rashid Taliban: The Power of Militant Islam in Afghanistan and Beyond, London, IB Tauris 2010

Alex Strick Van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn (eds) My Life with the Taliban, Abdul Salam Zaeef, London, C Hurst & Co Publishers 2010

Alex Strick Van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn An Enemy We Created. The Myth About the Taliban-Al Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan, Oxford, Oxford University Press 2012

Peter Bergen (ed) Talibanistan: Negotiating the Borders between Terror, Politics, and Religion, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press 2013

Anand Gopal No Good Men Among the Living: America, the Taliban, and the War through Afghan Eyes, New York, Metropolitan Books 2014

Anand Gopal and Alex Strick van Linschoten “Ideology in the Afghan Taliban” Kabul, AAN 2017,

Alex Strick Van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn (eds) The Taliban Reader. War, Islam and PoliticsOxford, Oxford University Press 2018.

By Special Arrangement with AAN. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.