September 26, 2019

Past Afghan elections have frequently been bewildering and surreal, even for those following the politics of the country for a long time. With this in mind, and taking into account the recent measures adopted to try to stave off a repeat of the chaos, AAN’s Thomas Ruttig, Martine van Bijlert, Ali Yawar Adili and Jelena Bjelica (with input from Obaid Ali) have put together this brief guide. It discusses crucial issues on and around election day that could both affect the election and indicate how the rest of the process might go. They discuss: the implications of the lack of reliable data, the likely impact of insecurity on turnout and vote shares, the likely role of social media in the election, the potential improvements and risks provided by biometric voter verification, the role of observers and agents, and the thorny issues of turnout and voter disenfranchisement.

1. Lack of reliable baseline data and of transparency

Elections in Afghanistan, in general, are complicated by a lack of reliable baseline data, including exact population figures and the total number of eligible voters. In a significant improvement over previous elections, the Independent Election Commission (IEC) has since 2018 sought to establish a fixed voter list that connects voters to specific polling stations. This gives greater control over where voters can be expected to turn up and limits the possibilities for mass ballot stuffing.

However, the key figures released by the IEC – on how many Afghans have registered to vote, and how many polling centres and polling stations are planned to open – are incomplete and contradictory, as they were during the 2018 parliamentary elections. This is concerning, as these figures form the foundation of the IEC’s measures to prevent and address fraud.

Inconsistencies, ambiguities and a failure to release or update figures may indicate that the IEC is either not fully in control of its own data gathering, management and vetting procedures, or that it is intentionally keeping the figures vague. This leads, at best to a lack of clarity and suspicions of manipulation, and at worst to providing actual opportunities to perpetrate and cover up fraud.

This guide looks at three types of data: the number of registered voters, the existence of inaccuracies in the voter lists, and the number of planned-to-be-opened polling sites.

Number of registered voters

The Independent Election Commission (IEC) has published the number of registered voters, district by district, and in total, on different pages of its website. The numbers differ between the pages, so that it is not clear what the IEC figure is.

On the last page of the master list of polling stations and registered voters, published here, the IEC gives a total of 9,665,745 registered voters (6,331,515 male and 3,334,230 female). This is also the figure the IEC provided to the media on 18 August 2019.

On the district-by-district page, however, the IEC gives no total. Readers, including AAN, need to do the sums themselves. Calculating the total on 21 September 2019, we came up with a figure of 9,663,813 registered voters (6,330,448 male and 3,333,381 female). The figures differ from the master list by almost 2,000, by more than 1,000 for male voters and by almost 1,000 for female. (1)

The website does not show when the data was entered (although there is a default date of 1 January 2019), or when it was last updated. It is possible that the IEC has weeded out duplications and errors since 18 August, but if so, it did not tell anyone or note this on the website.

Although the discrepancies are not large, the differences show that the IEC does not seem to double-check its own data entry or update its website, even in the crucial last week before the election when its main customers – voters, journalists and analysts – will be checking it. This may be indicative of a wider lack of capacity and/or a sloppy approach when it comes to the management, verification and dissemination of key data.

It may seem petty to draw attention to relatively minor inconsistencies and oversights, but past experience has shown that they may well be indicative of much larger problems, a fogginess that enables manipulation and undermines the credibility of the election results.

Inaccuracies in the voter list

More troubling than the fact that the IEC has published diverging figures, are the indications that the voter lists have not been sufficiently corrected. Inaccuracies in the voter lists was one of the major sources of chaos in the 2018 Wolesi Jirga election, when many voters found that their names were not on the list at the polling stations where they had registered, or that their names had not been recorded properly. The IEC has tried to correct the list in the run-up to the presidential election, but has by no means completed this task. The head of the Bamyan Provincial IEC, Qasem Qasim, for example, told AAN on 11 September that only 20 per cent of the voter lists in his province had been corrected. Qasim said the voter list would be “the most serious issue” on election day.

Widely inaccurate voter lists may compel the IEC to once again loosen the procedures that have been designed to prevent and track fraud, or else risk disenfranchising large numbers of voters. As in 2018, the IEC may thus decide to again allow people who are not on the list to still cast their votes. The eligibility of these votes could theoretically be checked after the fact, but the IEC is unlikely to have the time to do so, or the clarity of communication to prevent confusion and suspicion.

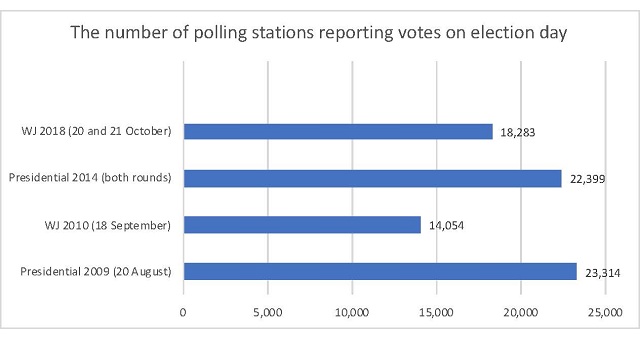

The number of planned-to-be-open polling centres

Equally significant are the inconsistencies in the number of polling centres and stations which the authorities say they plan to open or to keep closed, following security assessments carried out by the national security agencies. After the last parliamentary elections in 2018, the IEC (the members of which have changed; those who were in charge then are now in jail after convictions for large-scale ‘administrative fraud’) never publicised the final figures on how many polling centres and stations were open on election day. (It also never published voter turnout figures and, after the last presidential election in 2014, there was not even an officially-published result. The alleged results were leaked by one of the parties – see analysis here.)

Such lack of reporting of crucial figures and indices could happen again in 2019. Indeed, there is already confusion as to the number of polling centres that are judged to be in safe areas or protected sufficiently by government forces to be open on election day.

The master list of polling centres numbers 7,384 (see AAN’s just-published Election Primer); each polling centre consists of at least two polling stations, one for women and one for men. The IEC and the Ministry of Interior (MoI) had planned to open 5,373 of them on election day, but the MoI has now indicated that it is not able to protect 431 of these. These closed polling centres are distributed over 17 provinces (ie, half of all provinces), but are concentrated in five: Badghis, Balkh, Faryab, Ghor and Nuristan. Each of these provinces will lose a third or more of the polling centres which the authorities had said they planned to open. Maidan-Wardak loses more than a quarter of its centres, Samangan one fifth and Badakhshan, Farah, Jawzjan, Sarepul and Herat between 9 and 15 per cent of their centres. As the AAN Election Primer shows, yet more centres could prove vulnerable on election day.

It is not clear whether the declaration of 413 (and possible more) additional non-defendable polling centres is the result of government forces being overstretched, a changing security situation, or, at least partially, political motivations. There will definitely be a suspicion of the latter if it turns out that the now-closed centres are concentrated in areas where particular candidates were expecting to draw on important vote banks. For example, it is eye-catching that, with the exception of Farah, Nuristan and Maidan-Wardak, (2) those affected are mainly non-Pashtun-majority provinces. However, it is not known yet which districts in those provinces are affected, and it might well be that the Pashtun-majority districts in Balkh, Faryab and Jawzjan, for example, are also on the list. Even so, it is something to watch.

Adding to the confusion, IEC spokesman Zabihullah Sadat told AAN on 24 September that the government’s security agencies had yet to provide the list of 431 polling centres now to be closed to the commission; MoI representatives, meanwhile, told AAN they had provided the list. AAN has also seen another list of polling centres planned to be open, which was provided by the IEC to observer groups – and the figures on this list differed, yet again, from those on the IEC website.

The number of open polling sites and their geographical spread will have a direct impact not only on voter turnout, as fewer polling centres in a certain area means that people will need to travel longer to vote, but also on the likely vote share of each candidate. Any lack of transparency in this regard will feed suspicions that the IEC or the security agencies might be trying to influence the outcome of the vote by excluding certain areas.

It is crucial for the final list of planned polling centres be agreed on and publicised before election day, so that voters know where they can go, IEC staff know whether they need to turn up, and the IEC knows whether they can expect votes from the various location. This may seem obvious, but confusion over the final list has happened in the past and has been used to facilitate fraud.

For the same reason it is important that, during and after election day, the IEC establishes and communicates as soon possible which polling centres did indeed open and which stayed closed. The gathering of this information can take days, and sometimes longer, due to patchy communication, long travel distances and the intentional withholding of information by staff on the ground.

2. Physical security and media reporting

A major influence on which polling sites can open, how many voters turn out and what the relative vote shares of the candidates will be is insecurity. The Taleban have vowed to “prevent” the election from happening and have issued warnings, including against campaign events and election personnel. They have followed these up with three massive attacks (for detail, see our election primer). Apart from the Taleban, the local Islamic State (IS) franchise, called IS Khorasan Province, also constitutes a threat to voters, election workers and polling sites, at least in some places.

Meanwhile, local journalists who asked to remain anonymous, have told AAN about increasing indirect government pressure not to report security incidents, starting a few days before the election and on election day, with the aim of not discouraging voters from casting their ballots. This also happened during the 2018 parliamentary elections, when there was a tacit agreement between some key media outlets not to report security incidents until noon (AAN’s reporting here). Journalists have also said that IEC officials in the provinces have been instructed to not speak to the media. One reporter told AAN that in the last election IEC officials had been a major source of information; this time, he said, the ban “will cut us off from important information.”

The government push for a news blackout is controversial, and not only with journalists (see a 2014 discussion by journalists over the ethics of such a move here); it also makes it more difficult for voters who rely on local media for up-to-date information to judge if it is safe to go out to vote. In other words, failure to report attacks could endanger Afghan citizens.

Insecure areas also provide opportunities for fraud and manipulation. During previous polls, election material has been delivered to insecure areas, or to places – mainly district centres – that were government-held islands in Taleban-dominated areas. Sometimes, the material was redirected to the private houses of local strongmen and then used to stuff ballots. Despite new preventive measures (see below), there is still the chance that this kind of fraud might be attempted again in 2019.

Particularly relevant to watch in this regard, are the polling centres that have remained on the official IEC list, despite being in districts fully under Taleban control. Examples of such districts include:

In Kunduz, Aqtapa and Dasht-e Archi are both under full Taleban control. Dasht-e Archi’s district centre was stormed by the Taleban on 7 September (media report here). At that time, district governor Nasruddin Sahdi told AAN that local security forces had retreated to Khwaja Ghar district in neighbouring Takhar and there was no plan to conduct a counteroffensive ahead of the election.

In Takhar province, the districts of Yangi Qala and Darqad have been changing hands between the Taleban and the government (see here and here). The authorities say they plan to open five polling centres in Yangi Qala, even though, according to local elder Haji Asad, the district governor and administration are operating in exile from the provincial capital Taloqan. Similar concerns have been raised by the district governor of another Takhar district, Ma’alem Hassan of Khwaja Bahauddin. He told AAN that, because of the large Taleban presence, he expected that only two out of a total of eight designated polling centres would be able to open.

In Ghazni province, it is suspicious that in Andar district, which is also under full Taleban control, the authorities plan to open 16 polling centres, spread over nine villages. Particularly striking is the centre in the small village of Shamshai. It has sevenpolling stations, enough to cater to 2,800 voters, a large number for such a village.

In Logar, the province from which President Ashraf Ghani’s family originates and is said to still own land, the village of Surkhab has two polling centres. Yet, locals told AAN it would be difficult even for election material to reach there; usually, only heavily-armed convoys make it to Surkhab to supply the local police post. They said they thought the heavy Taleban presence in the district would deter voters from casting their ballots even if the ballot papers manage to arrive.

Significant changes to the local security situation on election day, or during the few days before, could also point to attempts by localofficials, strongmen or campaign teams to either prevent voters coming out in favour of a certain candidate or use the insecurity as a cover for fraud and manipulation.

3. Vote security

One piece of good news seems to be the significant technical improvements in the software of the Biometric Voter Verification (BVV) devices, designed to prevent multiple or other illegitimate voting from taking place. During the 2018 parliamentary election, many of the devices malfunctioned, or staff were not sufficiently trained in their use, so that the IEC also allowed people to vote without their biometric data being captured and verified.

This time, additional measures have been introduced to prevent mass fraud, such as ballot stuffing. These measures include time stamps marking when the BVV device starts and stops working, and when data is entered, and QR coding of polling stations, ballot papers and voters’ IDs. However, there might still be undetected backdoors in the system that could allow manipulation. As experience in the wider world shows, hackers are often a step ahead of safety measures and quick at finding ways around security systems.

Although key election stakeholders have told AAN that IEC staff were trained earlier and better than in 2018, it is still not clear whether all BVV devices will work, whether all election staff have really understood the complicated technology and whether they will handle it as designed, especially in stressful situations. Mass malfunctioning, a lack of capacity to properly handle the devices, or the intentional failure to use them could still create opportunities for fraud, or a situation in which safeguards need to be abandoned again in order to avoid voter disenfranchisement (as was the case in the 2018 election).

This year, the IEC has increased the number of polling stations – to 29,586 in total – in order to reduce the number of voters that need to be processed in each station, from 600 to 400. In this way it hopes to avoid a repetition of the administrative chaos in last year’s election (see AAN reporting here). However, there still may be long lines, given that all registered voters are now supposed to cast their vote in a much shorter time, within eight hours, between 7am and 3pm. This means that a polling station with the maximum 400 voters (of which there are many, both in cities and the countryside) where all voters turn up, the electoral staff will need to keep the crowd moving at an average speed of a little over a minute per voter. This means that every minute, a voter should enter and exit the polling station; once inside they can spend a few minutes to go through the entire procedure – checking whether their name is on the voter list, having their photo taken, getting a QR code for the ballot paper printed and casting a ballot – as long as they do not stop the queue from moving. It is not clear whether the two extra hours which can be added at the end of the day if a polling centre is still crowded, will be sufficient.

4. Spinning: The role of social media

The role of social media in Afghanistan’s elections has increased over the years. It has both widened the reach of information, and added confusion and noise to the process. In this run-up to this election, civil society activists have, for instance, warned AAN that the Ghani campaign seemed to be working on a “social media balloon” – ie a great flurry of activity using large numbers of accounts on several popular social media platforms, including presumably bots and fake accounts, to create the impression of high pre-election mobilisation. Such efforts, if true, may simply be part of a ‘regular’ campaign strategy that seeks to project widespread popular support. But the suspicious can imagine it later justify implausibly high turnout figures, coupled with election-day footage of long queues at the polling stations, that could then be posted and reposted en mass. As one activist warned AAN, the wrong impression can be created by photos of long queues; they could either reflect a lot of interest by many voters, or the inability of the IEC staff to properly process the voters that have turned up.

So far, there is little indication that turnout will be high. Campaigning has been lacklustre and does not seem to have reached many rural areas. Even in cities like Kabul and Herat, there were visibly fewer candidate posters than in previous elections (for Herat see this AAN dispatch). In Kabul city, where during earlier elections, there was barely a spare place left on any wall, now even major thoroughfares show only a few posters, and many shop windows are conspicuously empty. Many AAN interlocutors, Afghan and international, and even those who are officially campaigning for certain candidates, report low interest in voting, even in the big cities and even among their own staff.

Candidates have largely avoided travelling to the provinces during the one month campaign that started in late August (see a media report here and AAN’s reporting from Herat here), with the exception of Ashraf Ghani and his team. In the middle part of the campaign, even Ghani reverted to mainly addressing election meetings through video conference (he has had over 40 of these virtual meetings, according to a member of his campaign team). Travel to the provinces by candidates has only picked up in the last week of the campaign, with Dr Abdullah and Rahmatullah Nabil, and again Ghani, attending events in multiple provinces.

When it comes to campaign logistics, media outreach (including social media) and advertising, Ghani seems to be well ahead of his expected closest rival Abdullah. His team has hired media and communications specialists (apparently including young professionals with experience in high-profile US campaigns), has a large fleet of cars at its disposal to transport organisers and voters, has spent much money on TV and radio advertising and has provided district mobilisers with generous funds to entertain voters and local ‘political brokers’ who claim to be able to “ediate between candidates and vote banks (for more details see this 2009 AAN paper). The Ghani campaign has even blocked a whole section of a central Kabul street, now nicknamed Kucha-ye Entekhabat (Election Lane), from where it coordinates its campaign efforts. However, even this impression of heightened activity might be a result of the campaign itself. On Facebook, for example, Abdullah far outnumbers Ghani in ‘likes’: 4.3 million to 1.7 million (figures checked at 6pm on 23 September) – bearing in mind, of course, that likes can also be generated and bought.

AAN has also been shown a smart phone app that was developed by the Ghani campaign to send and collate real-time results from polling centres. The aim appears to be able to announce ‘exit poll-style’ results already on election day. However, given the often protracted process of complaints and adjudication, the actual election results could and – given the record of previous elections – are likely to differ significantly from the count on election day. Nonetheless, if the app was applied effectively, such an announcement could create a ‘first impression’ that resides in the memory of voters and reporters and sets up a narrative that diverging official results might struggle to correct.

5. The role of observers and agents

The presence of candidate and political party agents and independent observers is supposed to prevent on-the-spot manipulation and increase the legitimacy of the poll. Particularly the two top candidates, Ghani and Abdullah, have registered high numbers – each in the tens of thousands. The number of independent observers is lower, but still significant (see AAN’s election primer for details). However, previous elections have had similarly high, or even higher, numbers of observers and agents (around 200,000 in the 2014 presidential election, see AAN reporting here) and they provided no guarantees against mass fraud. Observers and agents can be vulnerable to threats and co-option, particularly in insecure areas, and have in some cases been involved in manipulation themselves, together with others. It also remains to be seen whether all staff and observers who were trained and paid actually turn up on election day.

It is also unlikely that observers and agents will be spread evenly over the country, including in the more insecure – and therefore more fraud-prone – areas. Observers such as Samir Rasa, spokesman for the Free And Fair Election Foundation of Afghanistan, say they fear “the lower the level of monitoring of the election process, the higher the level of fraud in different parts of Afghanistan.” The near complete absence of international observers in polling sites outside Kabul, and even in most of the capital, is another negative impact of the deterioration of the security situation. During the first post-2001 elections, their physical presence encouraged Afghan observers and contributed to their independence.

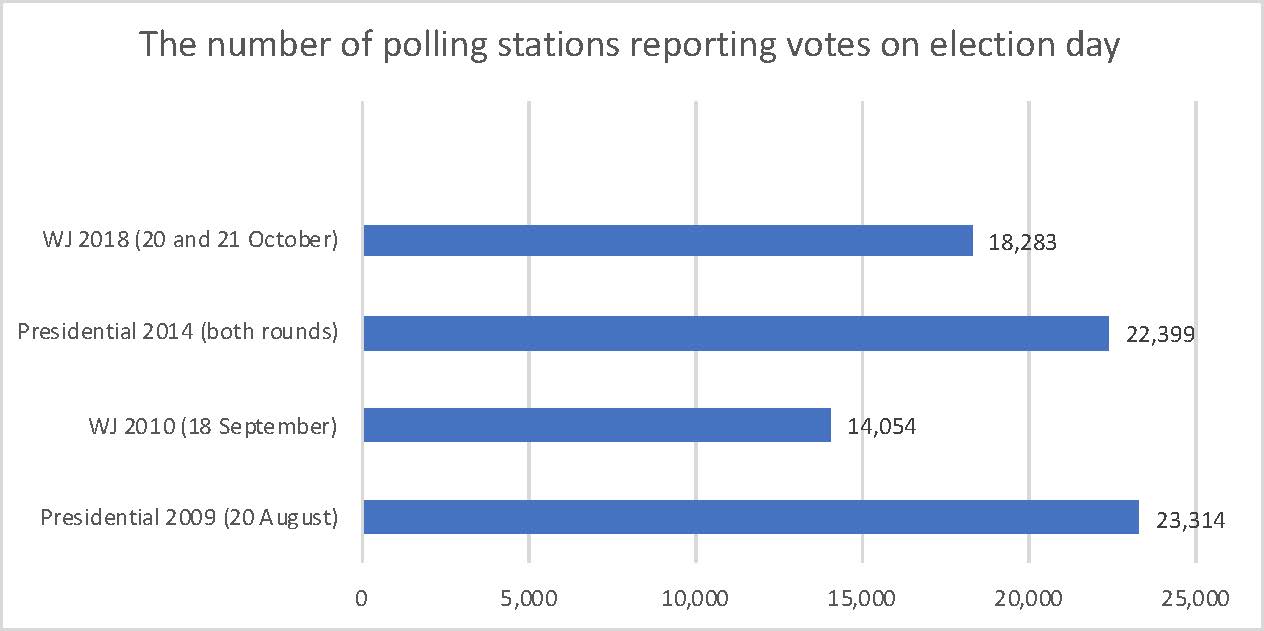

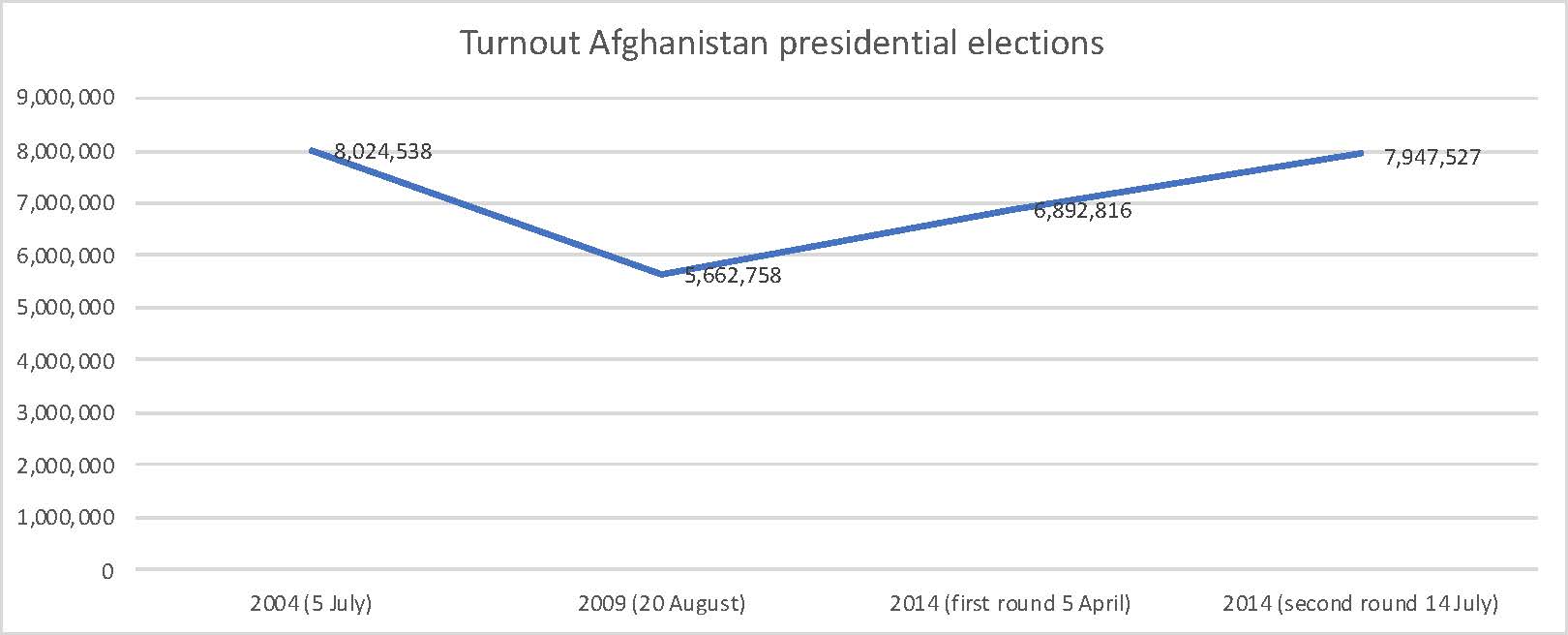

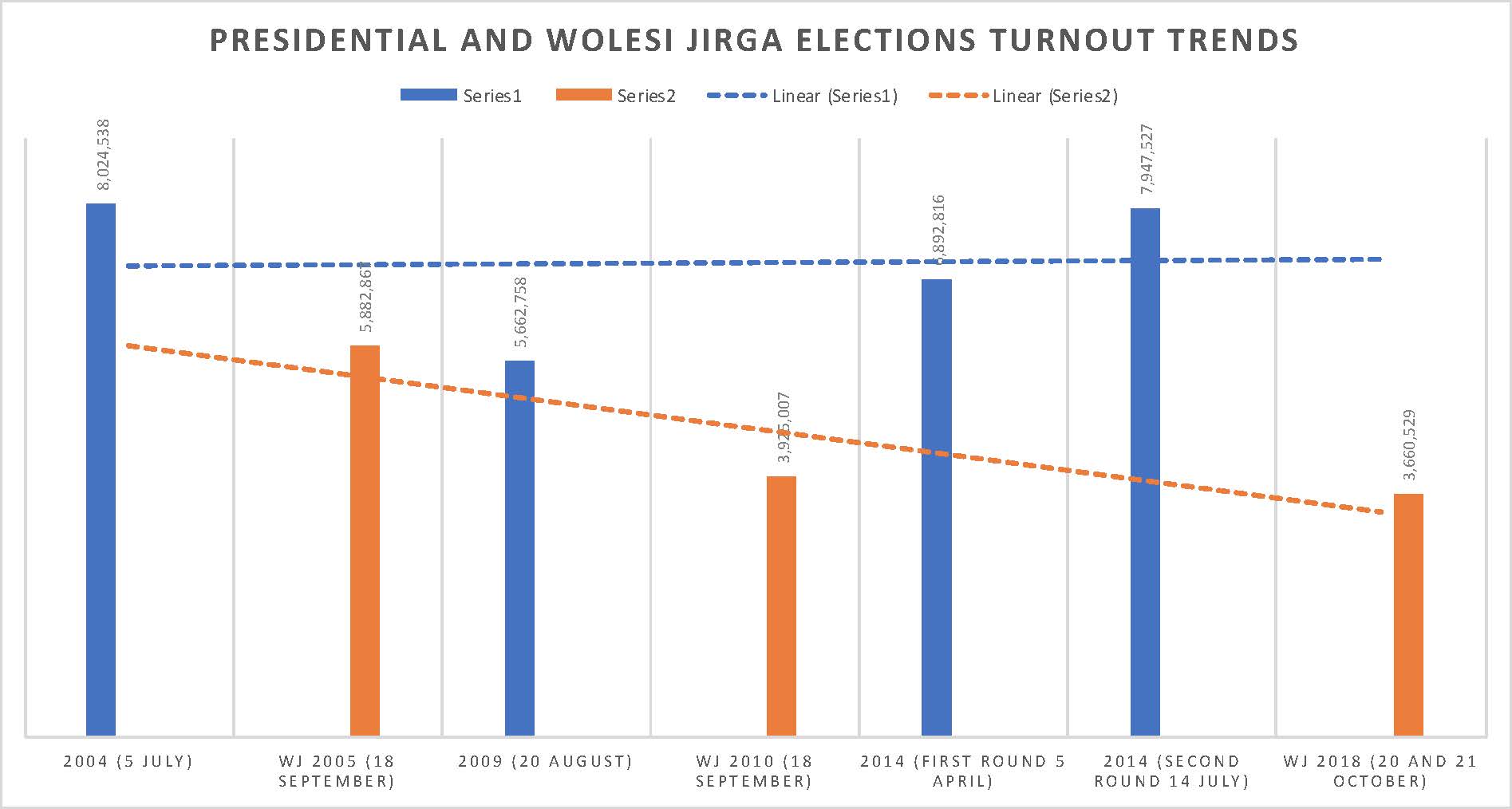

6. Turnout and disenfranchisement

One of the keys to the legitimacy of the forthcoming election will be turnout and its ethno-geographical spread. Activists close to the Ghani campaign say they would consider a turnout of 4 to 4.5 million a success. However, “campaign and government officials” quoted anonymously by The Guardian expect something “closer to the 3.6 million ballots cast in last year’s parliamentary vote.”Some international interlocutors in Kabul even told AAN they thought the real figure might be closer to 1.5 million. And indeed, a combination of insecurity, an insipid campaign, a choice between frontrunners who are incumbents, and the fact that there is no simultaneous provincial council election to attract voters with a local interest may dampen the numbers of Afghans turning out to vote. And even at the high end of the expected turnout – 4 to 4.5 million voters – this would still only represent about half of the 9.6 million people who have registered, and only a third of the lowest estimate of the number of Afghans of voting age, 13.5 million.

It also needs to be scrutinised how even or uneven the turnout is countrywide and whether any of the relevant ethno-political groups have been disenfranchised. As discussed, this can both be a consequence of operational choices by the IEC (most notably the opening or closing of polling centres and, earlier in the process, of registration centres – see also this AAN dispatch) – and of uneven security conditions across the country.

The general distribution of polling sites in this election is, in general, heavily tilted towards urban areas. Many rural citizens are being effectively denied a vote because of where the insurgency and government is each strongest (see AAN analysis here and here).

Looking Ahead

After election day, the next main vulnerability in the process is when the votes are checked and tallied in the data centre in Kabul. Previous elections have shown that it is vulnerable to attempts at post-factum manipulation and these are difficult to track and detect. Observers’ and agents’ access to this process is more limited than at the polling sites where the voting, counting and data transfer are done. (At the same time, it would also not be advisable to allow observers access to all data and the features of data security measures, in order to prevent them from trying to manipulate them.)

After the count come the complaints and complaints adjudication process which is often controversial and equally open to manipulation, as well as discretionary or seemingly random decisions. In 2014, there were mass disqualifications of votes that were ruled invalid in the complaints process, followed by counter-complaints that led to the re-qualifications of some of the votes, and to great confusion (read an AAN snapshot here; for an overview over the almost four months-long painful aftermath see part 1 of this AAN dossier).

One of the main features to watch is the level of transparency in terms of the adjudication criteria, the decision-making process and the final decisions. It is to be hoped that the new Electoral Complaints Commission (EEC) will not follow the bad habits of its predecessors, which included both not documenting their decision-making processes and reasoning and not disclosing their decisions to either the complainants, the targets of the complaints or the wider public. This is particularly relevant, given that in almost all elections so far the actual outcome, in terms of who wins and who loses, is determined in the process of complaints adjudication (and the resolution of the conflicts that flow from it).

According to the IEC’s electoral calendar (find it in the annex to this AAN dispatch), (3) official preliminary results are scheduled to be published on 19 October. What is more important than whether the IEC will be able to meet this date, is whether it will be transparent about the reasons for possible delays. In the meantime, a key feature of the much needed transparency will be the timely release of detailed partial preliminary results by the IEC. Any lapses in this regard should rise to greater scrutiny.

Finally, one of the concerns is that the 2014 presidential election may have created a precedent. The controversies around the count of the second round at that time were resolved through outside mediation and an improvised solution that allowed both key candidates to form a government together. United States diplomats in Kabul have, however, made it clear there is no appetite to do another ‘Kerry’, a reference to the mediation by then US Secretary of State John Kerry that resulted in the National Unity Government deal between Ghani and Abdullah (see AAN reporting here). This sentiment is likely to be more widely shared. However, if the disagreements over how to count vote does result in deadlock, as it has in almost every election so far, it will be difficult for international stakeholders such as the US, the United Nations and the European Union, to stand back and just watch.

By Special Arrangement with AAN.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.