September 25, 2020

On 8 September, a former senior US State Department official tweeted a remark on the long-standing border dispute between Afghanistan and Pakistan, unleashing a firestorm of comments from every level of Afghan society. The tweet came just days before the start of the intra-Afghan talks in Doha, Qatar, when tensions were already running high.

Afghan politicians of national stature know that the Durand Line is an internationally recognized border. Fanning nationalist or irredentist claims detracts from negotiating peace and economically beneficial ties between 2 countries,’ tweeted Alice G. Wells, former principal deputy assistant secretary for South and Central Asia.

This missive came in response to an earlier comment by Afghan vice president Amrullah Saleh who said: ‘No Afghan politician of national stature can overlook the issue of Durand Line. It will condemn him or her in life & after life. It is an issue which needs discussions & resolution. Expecting us to gift it for free is unrealistic.’

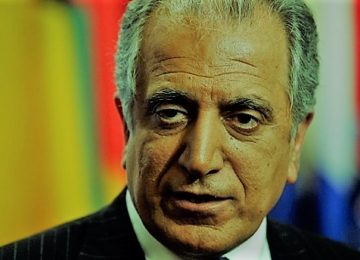

Wells’ views invoked the elephant in the room for the intra-Afghan talks in Doha. The unresolved question of the 2,640 kilometers Durand Line between Afghanistan and Pakistan will be an enduring source of instability, regardless of the outcome of the talks. While the negotiations in Doha between the Afghan government and the Taliban seek to reach a consensus over internal political, security and human rights issues, Pakistan remains a longer term impediment to external stability and the Durand Line is a significant factor. While US envoy Zalmay Khalilzad hailed the ‘important role’ played by Pakistan in facilitating the start of the negotiations, for many Afghans the nature of that role over the past few decades and the enduring border issue may be a snag in any agreement reached at Doha.

The significance of the Durand Line

In the treaty signed in 1893, British diplomat Sir Mortimer Durand divided the Pashtun heartlands by limiting spheres of political influence of then-Afghan King Abdurrahman Khan (1880-1901) as a buffer zone between British and Russian interests. To this day, Afghanistan has never accepted this boundary; Afghan historians and legal scholars emphasise that the Durand Line was merely an understanding meant to delineate spheres of influence, and not intended to serve as borders of a future state.

Although it is officially recognized in the United Nations and throughout the international community as Pakistan’s western border, the Durand Line nonetheless divides Pashtun lands, tribes, and families and remains one of the sources of the instability which has plagued the region, especially since the creation of the Pakistani state. In 1947, Afghanistan was the only country in the world to oppose Pakistan’s membership to the United Nations, on account of its refusal to recognize the Durand Line, and demanded that Pashtuns living on the Pakistani side of the line be given the right to self-determination.

‘As long as there is war in Afghanistan that directly affects the Pashtun regions across the Durand Line in Pakistan, there will be no peace. Stability and prosperity too will defy both countries,’ said Abubakar Siddique, editor of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Gandhara website, and author of The Pashtun Question: The Unresolved Key to the Future of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

This border dispute remained a constant point of friction between the two neighbours, especially when Pakistan became part of the US sphere of influence during the Cold War. The signing of a mutual defense treaty with the United States in 1954, followed by a CIA airbase in Peshawar, and entering the CENTO military alliance (aka the Baghdad Pact) in 1955 further assured international backing for Pakistan on the issue.

Having been unsuccessful in several border clashes in 1949-50 and again in 1960, the Afghan government briefly adopted a new approach to resolving the issue. Prime Minister Mohammad Musa Shafiq, who had successfully resolved Afghanistan’s longtime water dispute with Iran, put out feelers in 1973 to Pakistan’s then-President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Yet, the nascent process ended in July of that year as Shafiq and the Afghan monarchy were overthrown by a coup d’état by Prince Mohammad Daoud, a staunch opponent of the Durand Line.

Since then, the situation remains unchanged. In 2001, even Taliban leaders would not accept the Durand Line when former Afghan Interior Minister Abdur Razzaq led a delegation to Pakistan. And, as recently as 2017, then-President Hamid Karzai continued to challenge the 1893 treaty, saying Afghanistan would ‘never recognize’ the Durand Line.

Although Afghan politicians now rarely use this emotive cause to rally popular opinion — and it is doubtful a formal legal challenge would ever be mounted — the Durand Line is the elephant in the room in every discussion with Pakistan.

‘While the two countries have had different positions on the issue, the environment is not conducive for discussions,’ said Kawun Kakar, who served as legal advisor to former Afghan President Hamid Karzai, and later as a senior advisor to the minister of justice. ‘The ultimate resolution of the matter will require a close and constructive relationship. The two countries must first tackle the immediate pressing issues of terrorism and extremism, trade and commerce, refugees, non-interference, and other such issues.’

No resolution, no stability

In the context of current peace talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government, Afghan-Pakistan border issues are not on the agenda, nor are they expected to be an impediment to any eventual peace deal. Yet, a resolution of the external border dispute is as fundamental to stability as an internal peace deal as long as instability continues to flow across the border.

Even so, many maintain that settling the Durand question would not be sufficient in addressing far more central setbacks to peace and stability, such as the narcotics trade, sanctuary to terrorist groups and direct support to the Taliban.

‘Resolution of the Durand Line does not guarantee peace and stability,’ argues Helena Malikyar, a historian and Afghanistan’s former ambassador to Italy. ‘Pakistan’s long-held “strategic depth” policy, stemming from its fear of India’s influence in Afghanistan, would not be achieved solely through the recognition of the Durand Line by Afghanistan. Islamabad will only be satisfied if it is confident of having sway over the government in Kabul.’

As long as the Durand Line continues to partition the Pashtun heartland between two separate nations, it is unrealistic to expect any predominately Pashtun government of Afghanistan to accept and recognize it as a national border. For Afghans, there is powerful symbolism in the Durand Line; it is widely viewed as a historic wrong that must be redressed, however unlikely the prospect. Yet, Pakistan considers the line fundamental to its territorial integrity: it is ‘viewed in Islamabad as existential’.

‘Regardless of the cliched Afghan position on the border, Pakistan finally decided to bury the issue by putting up an elaborate 12 feet modern fence on the 2560 km border. The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa part — 1,350km or so — is almost done, and work on the rest continues,’ said Imtiaz Gul, a Pakistani political analyst. ‘The modern fence on the border to Afghanistan is a message that this is an internationally recognized border and we mean to protect it.’

Today’s ongoing talks in Doha between Taliban and the government of Afghanistan are the most important peace initiative since the 2001 invasion. Yet, these talks should be seen for what they are — a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for achieving peace for the long-suffering Afghan people. Internal stability is necessary but ending malign external influence is equally important. That will take settling the manifold disputes between the government of Afghanistan and Pakistan. The resolution of the Durand Line is possibly the most difficult of these, and will remain at the top of Afghanistan’s foreign policy agenda. Compromise may be possible, but as Vice President Saleh tweeted, ‘Expecting us to gift it for free is unrealistic.’

Courtesy: Le Monde diplomatique