December 3, 2020

At a time when Afghanistan’s economy continues to deteriorate due to intensified conflict and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, AAN researcher Reza Kazemi, gave a voice to daily-wage laborers who flock to busy town squares to find work and are among the poorest in the country. This report is based on his observations and conversations in the major western city of Herat, a hotspot for such work. The salient findings of the report are presented here, followed by the detailed report.

Report Summary

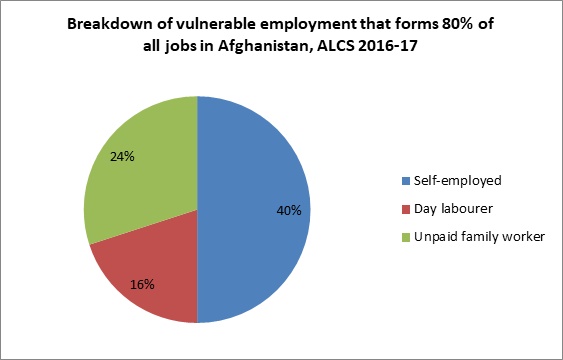

- 80 per cent of the Afghan workforce are in ‘vulnerable employment,’ with high job insecurity and poor working conditions, according to the Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey 2016-17, the latest data available at the moment.

- An estimated 16 per cent of the vulnerably employed are daily-wage laborers, an indeterminate number of whom gather at busy city intersections, looking for work that, if found, only provides their families with a hand-to-mouth existence. Herat province, particularly its capital Herat city, has been a hotspot of such work in the country.

- Daily-wage labor has multiple interconnected causes including violent conflict pushing people out of their villages to already overcrowded cities, population growth, lack of pro-poor development and recently the impact of Covid-19.

- Given the exacerbation of most of these factors, it is likely that vulnerable employment, including daily-wage work, has expanded since the 2016-17 survey.

This report starts, by giving space to one daily-wage laborer and his story. It then broadens the perspective to the situation of daily-wage laborers in Herat city by focusing on those that are gathering at specific intersections in search of work. Next, it discusses daily-wage labor as a category of vulnerable employment in Afghanistan, with special attention to Herat province. It finishes with thoughts on what daily-wage labor tells us about Afghan society, in which large numbers of people have been pushed to more severe forms of vulnerable employment and poverty.

A worker’s voice

The following personal narrative of a daily-wage labourer illustrates how such workers find work, what they earn and what they need to earn in order to cover their costs.

Farid, aged 45, has basic literacy and numeracy skills and is the sole breadwinner for a household of five: himself, his wife and their three unmarried children. For well over two decades now, he has mostly worked on a daily-wage basis, both as a migrant in Iran and after he returned to Herat in the early 2000s. In Herat, he has mainly found work at the bustling Badmurghan intersection in the south of the city – a town square locally called sar-e gozar (literally ‘in the passageway’). Men come here to offer themselves up for work, waiting for passers-by to hire them, some resting in the pushcarts they brought along, others with a shovel or other construction tool next to them. When the author spoke to Farid in mid-July 2020, he had temporarily found more permanent employment as a watchman for a construction site in a well-to-do area not far from the centre of the city:

I got to know the person who owns this land and is building a posh house on it through an acquaintance. He brought me here to watch his construction materials and tools like steel rods, cement, bricks, shovels, pickaxes and wheelbarrows, especially at night when everyone else working here goes back home. I go home after two or three days [for a break]. I earn 270 Afs a day (currently 3.51 USD)… I couldn’t bargain with my employer because there’s little work and many workers [in the sar-e gozar].

About a month and a week later, towards late August 2020, Farid was back at the sar-e gozar, having been fired:

The employer rejected me a few days ago. He said, “Pack your things, here’s your pay for the days you worked and go.” He made an excuse, saying that I hadn’t been present at work for some hours one day. I packed my things and went. He doesn’t give me my livelihood; only God does. I worked there for 37 days and made 9,990 Afs (129.74 USD). And that was without breakfast or dinner. For lunch, I ate along with the other workers; for breakfast and dinner, I prepared and ate something on my own.

After being unemployed for some days, Farid got some construction work in a nearby mosque in late August. In early September, he was again back at the sar-e gozar, looking for work.

When asked about whether the money they made was enough to cover their needs, a common answer by Farid and other workers living in similar circumstances was that they lived a life of “bokhor o namir” – “eat and don’t die.” They said they would need to make about 500 Afs a day (6.49 USD) to be able to survive – that is, if they already had a roof of their own over their heads, did not frequently host guests and no one in the family fell badly ill. They said that on average they made about half that amount, when they were fortunate enough to find work at all. These anecdotes are more or less corroborated by a 2016/17 study by the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs that found that daily-wage labourers worked an average of two to 13 days per month with a mean income of 313 Afs (4.06 USD) for each day of labour.

Daily-wage labor in Herat city

Farid is one of many. In the early mornings, labourers from the city and some nearby districts as well as displaced persons from neighbouring provinces such as Badghis amass at specific sar-e gozars in search of work. These sar-e gozars are usually strategically located at or near busy intersections with heavy traffic and intense commercial activity. Sometimes, against the backdrop of sar-e gozars in expensive residential areas, the groups of clearly poor and often malnourished daily workers starkly illustrate the widening social inequalities, not only between groups of people but also between cities and villages.

Take the Badmurghan sar-e gozar frequented by Farid. Located not far from a key marketplace and the provincial police office, it is one of the busiest and most congested intersections in the city. Shoppers go there for food, fruit and vegetable stores and vendors, photography shops and businesses offering music and film services for ceremonies such as weddings, to name but a few. Over time, the intersection has evolved into a commonly known meeting point between those looking for work and those looking for workers.

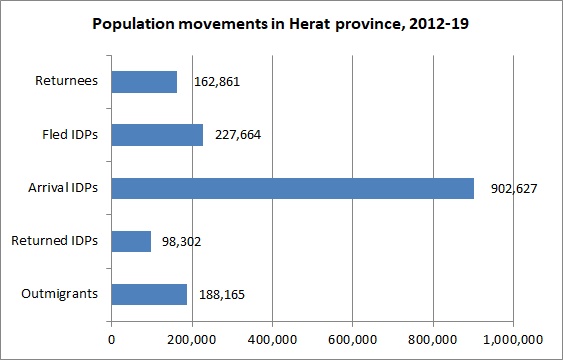

The prevalence of daily-wage labor is partially a result of massive population movements – particularly the influx of tens of thousands of people displaced mostly by conflict between 2012 and 2019. These population movements, in particular of internally displaced persons (IDPs), have made Herat province, primarily its capital Herat city, an increasingly difficult space for living and working. Many IDPs and returnees from Iran have resorted to daily-wage labor as their main, if not only, chance to earn money, according to the author’s conversations with laborers, including returnees, long-term residents and an official from Herat’s Labor and Social Affairs Directorate.

In an interview with AAN, Zubair Rauf, an official at Herat’s Labor and Social Affairs Directorate, listed seven sar-e gozars in and around the city where daily-wage laborers gather, one of which, he said, has become a hotspot for IDPs from Badghis province looking for work. He said the number of laborers gathering fluctuated, depending on the season, with numbers tending to increase towards autumn and winter when agricultural and other work, for example in brick kilns, decreases. However, he said that each sar-e gozar was frequented by an average of 400 to 500 laborers on a daily basis throughout the year. For these parts of the city alone, that adds up to several thousand people trying to get work every day.

In mid-August, one daily-wage laborer described to AAN the daily routine he has observed at two sar-e gozars – one in the south and the other in the north of the city:

I came here [Badmurghan sar-e gozar in the south of the city] this morning about 7:30 am, but haven’t found any work yet. Because I feel pain in my legs, I can’t go to Ghor Darwaz [another sar-e gozar in the north of the city] to see if I can find work there. When I came here, there were many people, but now there are fewer. They go from one sar-e gozar to another. When it gets to 9 or 10 am, they go to some cheap samavari (teahouse) to have some tea. When there’s no work, they return home empty-handed.

There are different people coming here. Some are from Badghis. Some are returnees from Iran, some are from the villages around the city and some are from the city. Their numbers only increase and never decrease. By around noontime, many go to this mosque here and do ablutions and say their prayers. If there’s no money and no charity bread or food, they fast. By the evening, those who are from the city or villages around the city go back to their houses. Those who are from Badghis spend a week or so in some inexpensive samavari or mosaferkhana (inn) and then return to their families for a visit… There are two kinds of work, kar-e sakhtemani (construction work) and hammali (porterage), but workers like me do any work that comes our way. In construction, we work helping masons and carry sand, soil, gravel or other construction materials like cement, plaster and tile. In porterage, we load and unload anything, like wheat, tyres and other goods and do other things like carrying people’s household items when they move house, washing their carpets and doing any other work they ask us to do.

Those ending up at sar-e gozars have generally run out of other options to find work. They lack wider social networks from which to get more dependable employment. “Those who have contacts find work by receiving calls on their phones,” said a daily-wage laborer while waiting at a sar-e gozar for a potential employer. Daily-wage laborers also do not have the capital to start a little business of their own like some others who have managed to raise money including from short-term labor stints in Iran or borrowing from acquaintances or both. Such more fortunate people can become “rais-e khod” (“their own boss”), as a rickshaw driver who was previously a daily-wage construction worker phrased it. They are driving people or commodities around in rickshaws, running small grocery or other shops or working as vendors, hawkers or cart-pullers – the main forms of local self-employment. It may still be precarious and not very lucrative, but is a step up from those trying to secure work at the sar-e gozars.

Daily-wage labour in figures – and why they remain blurry

How many people in Herat – and countrywide – currently work for daily wages is not known. The existing data is inconsistent and often not comparable, mainly due to a jumble of different definitions used over the years. Even the latest data is years old. The most recent Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey (ALCS) is from 2016-17 (the sixth edition, the first was published in 2003). In conversations with AAN in mid-October 2020, the spokeswoman of the National Statistics and Information Authority (NSIA), Rohina Shahabi, said the NSIA had not reached an agreement with foreign funders (meaning the European Union) over how to carry out a subsequent survey round. She said the EU had asked for data collection to be sub-contracted to an external party while NSIA had insisted it was capable of doing the work itself. The author contacted the EU Afghanistan delegation for its take on the issue but did not hear back by the time of publishing. Therefore, Shahabi said, the NSIA has (with technical support from the World Bank) carried out a nationally funded survey called the Income, Expenditure and Labor Force Survey, which includes daily-wage work. She said preliminary findings would be published in the remainder of the current solar year 1399 (meaning by March 2021), but stressed that for the moment, no data from the study was available.

As for absolute numbers, the existing reports offer slim pickings. The National Risk and Vulnerability Assessment from 2011-12 lists, for example, that there were about 187,000 daily-wage laborers out of a total provincial population of 1,871,000 in Herat in 2011. At the time, Herat was the province with the highest numbers of daily-wage laborers, accounting for around 15 per cent of the national total, calculated then at more than one million (1,279,000). In addition, other research found that daily-wage laborers in Herat were earning less than those doing similar work in Kabul and Mazar-e Sharif. This author has come across corroborating anecdotal evidence that this inequality has continued: some daily-wage laborers involved in construction work said they had found higher – and more punctually paid – wages outside Herat in, for example, Lashkargah, Kandahar or Kabul cities.

There are no more recent absolute figures for daily-wage laborers, neither countrywide nor for Herat, most likely indicating difficulties in data collection, such as decreasing access due to insecurity. The ALCS 2016-17 only gives percentages. It found daily-wage laborers made up an estimated 16 per cent of all those in vulnerable employment, while 80 per cent of all employment countrywide was considered vulnerable.

Given trends since the last ALCS survey of 2016-17 such as a deterioration in security and the socioeconomic situation, population growth and lately the Covid-19 pandemic (more on these below), it is likely that the extent of vulnerable employment, including daily-wage work, has expanded. Herat is likely to remain a major hotspot of daily-wage labor in the country, given, among other things, the influx of IDPs and a settled population growth of around 270,000 people since 2011.

The available data is, however, clear on one point: daily-wage laborers have been among those least securely and least gainfully employed. They and others in the vulnerable employment category account for by far the largest numbers of workers in Afghanistan. For most people looking for employment, ‘decent work’ is just a distant dream. According to the 2016-17 ALCS:

Of the total employed population, 20 percent – 1.3 million people – are underemployed, an indication that their jobs are inadequately providing sufficient and sustainable livelihoods. Moreover, 80 percent of all jobs are classified as vulnerable employment, characterized by job insecurity and poor working conditions. Only 13 percent of the working population of Afghanistan can be considered to have decent employment.

Daily-wage labor and the threat of even greater poverty

Already among the poorest of the poor, daily-wage laborer and others in precarious employment may now face even greater hardship. Firstly, the security situation has partly deteriorated further since preparations for ‘peace’ talks with the Taliban in the Qatari capital of Doha started this year. The conflict has damaged already struggling local economies and driven more people from their homes. This means, among other things, that in the relatively safer towns and cities near areas of conflict, breadwinners from internally displaced families may surge into local labor markets, increasing the number of those already competing for daily-wage jobs and further minimizing chances of anyone earning an income.

Exacerbating the consequences of conflict are the economic repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic. Daily-wage workers from Herat, were among the first to be hit by the fallout from the pandemic, with even less work available. In addition, hikes in staple food prices have burdened their already impoverished households further.

A third factor is the scale and nature of aid over the last twenty years, which, perhaps surprisingly, has been problematic, hindering sustainable growth and widening inequality. The economic growth that has taken place since 2001 has not been pro-poor. A 2010 AREU report, for instance, said poverty reduction policy in the country was at a “critical stage” because it “pays no attention to the societal factors that make and keep people poor,” including the “seeming co-optation of the poverty reduction agenda by a focus on economic growth and job creation with no attention to how the poor will benefit.” Reviewing about ten years of aid to Afghanistan (2002-12), a subsequent 2012 AREU report found that the “dividends and returns from nearly 10 years of aid to Afghanistan have been meagre for many Afghans. Many of the rural and urban poor are certainly no better off than before, and for many livelihood security is worse. The lack of employment and work in both the urban and rural labor markets is a testimony to this lack of progress.”

Similarly, a recent 2019 World Bank report replicated the point on the exclusion of vast swathes of the population from economic growth from 2009 to 2019, during which time the “welfare of the bottom 80 percent of the Afghan population has been in steady decline.” The World Bank report also said that “while poverty has intensified since 2012, inequality has declined as the transition [of security responsibility to the government in 2014] was accompanied by a large welfare loss among the most well-off.”

It is estimated that Afghanistan’s national income, or GDP, will have shrunk in 2020 by five to ten per cent. More alarming than this ‘negative growth’ is the projected poverty rate. The World Bank estimates a potential rise from 54.5 per cent of Afghans living under the poverty line to 61-72 per cent during 2020, according to the most widely used measure of poverty in the country. This would mean that not only will existing daily-wage laborers go even deeper into poverty, but that, most probably, more people will be made poor and some may be driven to the streets and also have to resort to daily-wage labor for survival.

Several large institutions have been calling for better social protection measures since 2012, indicating that not much has happened before or in the interim. The already mentioned 2012 Asian Development Bank report found that social protection was grossly insufficient and called for its improvement. A similar call was made by a recent September 2020 report by the International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth and the UN Children’s Fund Regional Office for South Asia that looked at the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic to social protection systems in countries in South Asia, including Afghanistan. Institutions involved in Afghanistan’s social protection sector are among the least funded and developed in the state, looking at their meagre share in the national budget. For instance, the sector has been allocated five per cent of the national budget for the current fiscal year 1399 (2020/21), which is incomparable to the top three sectors – defense (24 per cent), economic affairs (22 per cent) and public order and safety (15 per cent). The document outlining amendments to the current budget made because of the Covid-19 fallout mentions distribution of government-sponsored free bread to beneficiaries across the country and job creation mainly in the capital Kabul, amongst others (mainly anti-coronavirus health measures).

At the same time, options to mitigate hardship are squeezed off. The once popular option to migrate for labor stints from Herat to neighboring Iran, for example, in order to earn and send remittances back to families is increasingly unattractive, because of the devaluation of the toman, the Iranian currency (one million toman is currently exchanged for around 3,500 Afghani, one of the lowest rates on record). This is coupled with the fear of getting infected with Covid-19, which continues to rage particularly badly in Iran. AAN has heard from various sources in Herat that at the moment labor migration to Iran is, as a daily-wage laborer put it succinctly, “not worth it” (“namisarfa”).

All these factors mean that daily-wage laborers and many others in vulnerable employment have been and will continue to face hardship. The Covid-19 pandemic in Herat city has made an already bad situation worse, particularly during the partial lockdown from about late March to around late April 2020), as illustrated by the following quotes:

Corona made me completely jobless for a month or so. The police didn’t allow us to gather here [in the sar-e gozar]. I ran out of money, so I had no other way but to rely on my two brothers. One sells potatoes and onions on the street and the other works in construction in Iran.

Conclusion

The deterioration of Afghanistan’s economy means that, for many working men, the final option is to stand at a busy street junction, offering themselves up cheap for daily-wage labor. They represent large – and most likely growing – numbers of the country’s population that are sinking deeper into poverty. As the daily-wage workers in this report said, they have been reduced to lives of barely eating and trying not to die.

At the same time, the government and Afghanistan’s international supporters lack up-to-date information on those in precarious employment. Even if they did have that information, there would most probably not have been any interventions to help struggling workers such as daily-wage labourers. The dominant economic discourse of the last two decades, that favours some over most people and which leaves everyone to fend for themselves, has widened economic and social inequalities. These workers will most likely continue to be abandoned.

So there are no easy, quick solutions to the acute insecurity of the precariously employed like daily-wage laborers whose prevalence is the result of multiple interconnected structural factors. Persistent violence, a biased and shrinking economy and lately the pandemic have all wreaked havoc with the labor market. There is also the continued inattention of the government – and indifference from the Taliban. Neither is focused on the crumbling lives and livelihoods of the vulnerable. Only the lessening – and preferably a cessation – of the conflict would start to relieve the pressure that has been building up on Afghanistan’s marginalized workers, felt crushingly in the precarious lives of daily-wage laborers.

Excerpts from the Afghanistan Analyst Network (AAN) Report.

Courtesy: Afghanistan Analyst Network