April 11, 2019

Khalilzad, no doubt, has an unenviable task of treading through the Afghan landmines which may derail the process on any pretext and relegate it to square one. However, he holds the bait regarding withdrawal of American troops which has tempted the Taliban into sitting across the table and talk business. The positive vibes from Khalilzad and the Taliban are primarily rooted in President Trump’s indication of troop withdrawal which is reminiscent of president Mikhail Gorbachev’s announcement before the Geneva Accords in 1988 that the Soviet Union would withdraw from Afghanistan “with or without an agreement”.

The underlying issue is American haste to withdraw from Afghanistan which may have serious consequences unless a modus vivendi is agreed upon by the parties and an ‘interim government’ is put in place although such a proposition may appear a red rag to President Ashraf Ghani. However, for the time being there is a broad agreement on two out of four major issues that have been discussed between Khalilzad and the Taliban. Both Khalilzad and the Taliban agree to the US troop withdrawal against assurances from the latter of denying space to ISIS, al Qaeda and any other such outfit. But agreement on a ceasefire and a dialogue with the Ghani administration remains a bone of contention with the Taliban who consider Ghani an ‘extension of the US presence in the country’. Hence, to them, there is no need to engage the Ghani administration. But the Taliban have a bizarre logic against ceasefire. For them, a ceasefire would be a disincentive for their commanders and foot soldiers till the time Americans start withdrawing from Afghanistan. (The Taliban seem to have indicated that they would agree to a time frame of six months to one year for the US withdrawal from Afghanistan). Through this logic, the Taliban, in the interim period, want to continue their pressure on the Americans and the Afghan security forces.

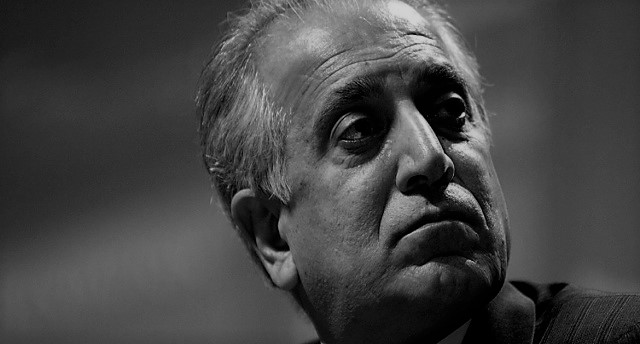

US Special Envoy on Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad had been in Islamabad this week as part of his renewed efforts to consolidate gains on future dispensation in Afghanistan and to review the progress achieved so far. Khalilzad’s sojourn sought to break new grounds for an acceptable solution to the parties and a smooth withdrawal of American troops from the war-ravaged country.

Khalilzad’s visit to Islamabad was primarily aimed at eliciting Pakistan’s support for talks between the Taliban and President Ghani. Pakistan already supports this proposal in the spirit of ‘Afghan-led and Afghan-owned’ peace process. However, there are other vital issues which call for substantive discussions between Khalilzad and the Government of Pakistan, including repatriation of Afghan refugees, drug eradication and discouragement of internal and external forces playing the spoiler’s role.

Concurrently, Afghanistan would first need (a) guarantees of non-interference from the neighbours; (b) an economic package from the international community after the withdrawal of the US-led coalition forces at least for one decade which may sustain Afghan security forces, bureaucracy and development projects in health and education sectors; (c) capacity building of Afghan institutions; (d) repatriation of refugees; and (e) preferential trade facilitation for Afghan products. The listed issues have so far not come up for discussion despite the fact that a sustainable peace in Afghanistan would need credible assurances of financial and material support from international stakeholders.

Second, Afghanistan’s immediate neighbours, including Pakistan, China, Iran and Russia, have lent support to the US for a negotiated settlement of the Afghan imbroglio. In particular, Pakistan was instrumental in convincing the Taliban to engage the Americans for a durable peace in Afghanistan.

Third, while the international community may offer certain assurances in the security and socio-economic sectors, the onus of providing stability lies with the Afghans. In this regard, the world community would be justified in seeking certain guarantees from the Taliban and other Afghan factions. It is reassuring that the Taliban are offering guarantees in denying safe havens to the ISIS and al Qaeda. They must also ensure eradication of war economy which is largely driven by narco-trade and gunrunning.

Fourth, women’s rights, including their participation in national life, is another significant issue which the Taliban have so far addressed cursorily. The Taliban must have realised by now that they do not live on an island or their view of religion is not the final wisdom to guide the people. In fact, their past performance portrayed a dreaded picture of religion which only contributed to tensions and hatred in the Afghan society. Admittedly, the Afghan society remains conservative where women have always been in the background, but the Islamic world has made substantive progress in ensuring women’s rights according to the teachings of Islam and encouraging them to play a vital role in the development of their societies. Therefore, in the future dispensation in Afghanistan, the Taliban’s policies towards women would be minutely watched by the international community.

Fifth, so far, the role of the United Nations in the forthcoming scenario has been hazy because of the direct involvement of the US in the Afghan affairs. However, the UN role in ensuring smooth transition in Afghanistan would be vital. Not only that, in the post-withdrawal period too, coordination of international assistance would be a gigantic task requiring UN expertise.

Keeping the fingers crossed, it is hoped that during the upcoming deliberations in Doha; there would be a detailed scrutiny of the aforementioned issues with some tangible measures to work upon.

The article is contributed by Asif Durrani who is a former Ambassador.

© Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS) and Afghan Studies Center (ASC), Islamabad.