I almost couldn’t believe my eyes when I finally received my visa to visit Pakistan. As an Indian-American, it was not an easy process.

That I was born in Hyderabad – Deccan, not Sindh – made India home, but rendered Pakistan almost impenetrable. My first application was scoffed at by the embassy in Cambodia where I initially applied.

But still I persisted, finally succeeding through the help of a college roommate, another Hyderabadi-American, who connected me with an official at a Pakistani Consulate in the US.

It always surprised me that nearly everyone I know has visited either India or Pakistan, never both. That these two nations are born out of the same cloth; out of a shared cultural and linguistic tapestry that stretches back millennia, has been unfortunately obscured by the politics of a few decades.

During Partition, my entire family, as far as I knew, decided to stay in the relative security of Muslim-majority Hyderabad in southern India. Amidst a slightly different situation, I could just as easily have been born in Pakistan. I was, of course, as proud an Indian as any, but that never hampered my curiosity for my fraternal nation.

We’re all scurrying to work in the United States, or vacation in Europe, when there is so much we can learn from our next-door neighbours.

I couldn’t remember the last time I was so excited to go somewhere new. I had already visited some 40-odd countries, attempting with each to broaden my understanding of the world. But there was something especially evocative about Pakistan.

As a South Asian Muslim, it was the indignation of a birth right interminably delayed due to political complications. After all, Pakistan was created in the spirit of inviting and protecting the rights of Muslims.

As a proud speaker of the language, I was also excited at revelling in Urdu in all its glory in Pakistan. The Devanagari script used to render Hindi is, of course, just as beautiful to my eyes. But I yearned to immerse myself in the elegant curves of Nastaliq outside of the select Muslim-majority neighbourhoods where it’s prevalent in India.

Of course, this was not the first instance I seriously considered visiting Pakistan. I flirted with the idea every time I was in India. Yet, I always let myself be dissuaded by a well-meaning family friend or another advising it was ‘too complicated a process, or worse ‘too risky.’

I wasn’t going to be stopped this time.

This time, passport and visa finally in hand, I boarded a train to Amritsar, on the other side of the Wagah border from Lahore.

My journey elicited stories from others also personally impacted by the Partition. I had an overnight layover in Ambala, where a Pakistani friend told me his grandparents lived before Partition. An Indian friend asked me to find the home his father had left in Lahore. Partition felt like recent history, despite having taken place 70 years ago.

I arrived at Amritsar Junction around 9am, exhausted from the modicum of sleep I could muster amidst the overnight frenzy of a train station. Still, I was eager to head as early as possible to the Wagah border to solve any issues I was worried might arise. I hailed a cab and sat in eager anticipation during the 45-minute drive.

As we pulled into the Attari Integrated Check Post, my passport and visas were verified. The taxi driver’s license was held before we were allowed to enter. I had meticulously prepared backup documents: duplicates of invitation letters, passport copies, photos; anything I could think of, the absence of which might justify rejecting my crossing.

I held my breath at each step, worried that a wrong answer or a misstep would get me denied entry or detained. Although the security was thorough, every single person I spoke with was courteous and professional, on both sides.

I was joined by a few working-class Indians: some Kashmiris, and a few Sikh pilgrims visiting temples in the Pakistani Punjab. Cleared through Indian security and customs, we boarded the bus to head to the famous Baab-e-Azadi.

I’d seen it before, ten years prior in my first trip to India from the States. I had come to Wagah to witness the daily military parade. Like every other visitor in attendance, I had no visa to cross then. The border seemed impassable then.

But on this day, Quaid-e-Azam’s portrait and the qaumi parcham welcomed me. It was an almost spiritual experience as I took my first steps into Pakistan. It was hard to believe. I would be the first in my family to ever visit Pakistan; a nation close to my heart as a South Asian Muslim, a nation separated from me as an Indian-American.

I would be joining the unfortunately small ranks of individuals who have recently experienced both India and Pakistan, communities cleaved apart after Partition that had lived peaceably together for centuries. I was about to see through my own eyes how Pakistan compared to its international perception and perhaps more intriguing, with its sibling rival, India.

My friend’s father was the first familiar face to greet me on the Pakistani side. The hour-long drive to Shahdhara, Lahore kicked off an unforgettable week.

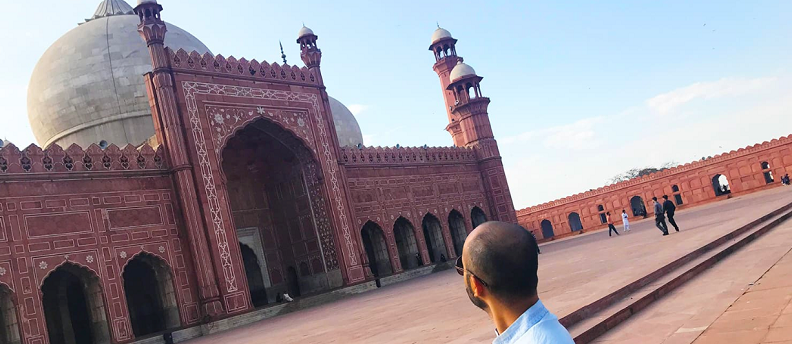

Watching the Mughal-era Baadshahi Masjid rise up in the horizon as we drove into the city was a majestic experience, perhaps rivalled only by joining the jamaat inside the following Friday.

I marvelled at the Lahore Metrobus, riding it routinely as I shopped for shawls at Anarkali Bazaar or kurtas from Junaid Jamshed.

I was even fortunate enough to participate in a Punjabi wedding, enjoying the most tender and flavourful mutton across any of my travels.

As memorable as my time in Lahore was, I had just uncovered a much more profound revelation. While there, I received an unexpected phone call from my mother in the States. The excited tone in her voice indicated something was up.

I had, in preparation for my trip, requested her and my dad to ask around on the off chance we might have any distant relatives who had migrated to Pakistan. Most inquiries had led to nowhere. It seemed like all of my living relatives stayed in India, or otherwise opted for the Gulf or North America.

However, on the phone this time, my mother informed me of recently receiving an invitation to a wedding in Chicago from a distant uncle. When she told him about my trip, he suggested a cousin of his, whose number he didn’t have.

However, on the phone this time, my mother informed me of recently receiving an invitation to a wedding in Chicago from a distant uncle. When she told him about my trip, he suggested a cousin of his, whose number he didn’t have.

My mom perused old phone books of my late nani to find this person’s number, a distant relative of whom she had heard, but never met. With this, my mom made her first call to Pakistan. She was ecstatic to deliver me the news, that I had a relative in Karachi who was excited to meet me.

I couldn’t believe it. I had lived 29 years of my life, believing my entire family (and by extension myself) to be solely Indian. That this journey might question that monolithic ancestry, and reunite me with family separated by Partition, imbued the journey with a much deeper sense of purpose.

Originally having planned just a week for Pakistan, entirely in Lahore, I changed my schedule. I ate as much chargha and murgh chhole as I could before I boarded my flight to Karachi.

When I landed at the Jinnah International Airport, I was the first in my family to meet Moin nana, the maternal cousin of my nani.

Given the distance, it was unsurprising that we only just learned of each other’s existence. More remarkable was how deep the familiarity still ran. I recognised him immediately, the spitting image of my nani’s younger brother in Toronto.

We quickly discussed our shared family. My nani had only met his older siblings in India over half-a-century ago. It was more than enough to forge the consanguine bond that tied us together.

I learned that Moin nana was born in December of 1947 just months after Partition. His parents packed up their life, and along with their kids, left Hyderabad in 1950. Like millions of Muslims immigrants, they were eager to settle in the Dominion of Pakistan and selected Karachi as their new home.

It was evident that Hyderabad remained with many of them. A replica of the char minar, Hyderabad’s most iconic landmark, welcomed me as we drove in to Bahadurabad. I recognised it immediately as an homage to the Deccan origins of the resident’s central Karachi neighbourhood.

Khatti daal and mahi khaliya cut adorned the dining table of my nana’s house, staples of Hyderabadi cuisine from 1,500 kilometres south.

My cousin, despite never having been to Hyderabad, could pull off a dakhini accent that wouldn’t raise an eyebrow near the original char minar. He introduced me to other relatives, as well as the best biryanis, niharis, and lassis Karachi (and perhaps the world) could offer.

I met friends from college and even attended a mushaira. I was beginning to see Pakistan less as a tourist and as more of an insider.

I cherished my time in Lahore, but I couldn’t shake the feeling of being somewhat of an outsider. But my newfound family ties alongside the cosmopolitan nature of Karachi erased that distinction. Here, ethnic Sindhis rub shoulders with Pashtuns, Punjabis, Baloch and even a few Hyderabadis like me. Karachi teemed with the infectious spirit of a bustling metropolis rapidly evolving, even reinventing itself, and I was hooked.

I know I’ll return someday, and soon. I intend to bring others along – to share the most important lesson I’ve learned.

My voyage to Pakistan was originally born out of intellectual and cultural curiosity. Driven by a desire to understand the broader canvas of South Asia, I thought I was heading to a foreign country. This Indian-American didn’t realise he was actually discovering another home.

This story originally appeared in Dawn News on June 20, 2017. Original link.