When Soviet Foreign Minister Edvard Shevardnadze visited Kabul and Islamabad in 1989 to discuss a peaceful transition from the Afghan war, the militants he sought to meet refused to give him an audience. A spokesperson for the fighters said they saw no reason to meet Shervardnadze once it became clear he had brought no new ideas from Moscow. “They had nothing new, and we had nothing new,” the spokesperson said. “So what’s the point?”

Twenty-eight years later, a shortage of new ideas is why a different superpower is still getting it wrong in Afghanistan. President Donald Trump’s plan for Afghanistan will reportedly allow for the deployment of 3,900 more troops in the hope of accomplishing what 16 years and 150,000 soldiers from a coalition of dozens of countries could not. And at home, Pakistanis tired of managing the fallout from an interminable war and being apportioned blame for not doing enough are reconsidering the merits of an increasingly asymmetric relationship with Washington.

Whichever way you cut it, a military solution to the Afghan war is as unlikely today as it was seven years ago. With the Taliban controlling 40 percent of Afghanistan, a few thousand additional troops are unlikely to alter the insurgency’s on-ground calculus. Three-fourths of Taliban financing comes from opium produced inside Afghanistan. In 2016 alone, the insurgency’s largest source of funds witnessed a 43 percent increase. A fractured government and its ineffective Afghan National Army has failed to demonstrate the ability to turn the insurgency’s tide. At the same time, the Taliban too are diversifying, limiting the extent of leverage Pakistan may have once had. Recent reports suggest that families of the Taliban leadership have relocated to Iran. Both Moscow and Tehran are actively engaged with the Taliban giving them greater strategic buy-in. The expectation that Pakistan alone can magically engineer solutions to offset Washington’s failings or Kabul’s shortcomings is thus flawed.

Pakistan’s frustration at getting shafted in the global blame-game on Afghanistan is legitimate. Nobody enjoys being cast as a recurring spoiler in somebody else’s forever war, least of all if you happen to be a key counter-terrorism partner that has sunk significant political capital into hosting and facilitating multiple rounds of peace talks, while single-handedly waging a large and near impossible counter-insurgency operation at home. At least two rounds of these talks in the summers of 2015 and 2016 were thwarted by Afghanistan leaking the news of Mullah Omar’s death, and the United States eliminating Mullah Mansour respectively. Since then, the reconciliation process has been in deep-freeze.

The United States, for its part, still hasn’t realized that an open-ended commitment in Afghanistan constricts the space for a political solution. Nor has it sought to rectify the Obama-era inconsistencies behind fight-talk-fight: In the United States, the Taliban are still not seen as a political reality and the Haqqanis remain blacklisted despite co-piloting an insurgency that Kabul has desperately been trying to lure to the negotiating table. And in spite of its histrionics (or perhaps because of them) Washington continues to misread the regional dynamic.

America’s invitation to India to get its hands dirty, while neglecting to include China and Iran, both of which are immediate neighbors, may go down as the biggest example of America’s regional myopia over the course of the war. China, as the second largest economy of the world and the single-largest foreign investor in Afghanistan, has been working steadily to create concentric circles of economic interdependence with CPEC as their center of gravity while shoring up geopolitical influence. China has also quietly engaged in backdoor talks with the Taliban since 2014, and has along with the US been a part of all major initiatives to bring about reconciliation. Half a dozen rounds of talks with the Taliban, either directly or indirectly with the group’s Qatar office, have taken place in Beijing and Urumqi, indicative of the fact that the Taliban accept China as a neutral arbiter.

Meanwhile, as Pakistan’s foreign minister completes the third leg of his three-nation tour to solicit support for Pakistan’s case, the opportunity costs of partnering with an unpredictable and overheated American war machine are slowly but surely being recalculated. True, the United States remains a major source of military hardware for Pakistan. The majority of U.S. military assistance to Pakistan comes in the form of Coalition Support Funds[i], reimbursements for expenses already incurred and compensation for facilities made available to the coalition forces through a decade of supporting America in Afghanistan. Of these funds, $50 million was withheld this year. Pakistan is also a major non-NATO ally, a status that is of symbolic value but not much else: It allows Pakistani military officers to gain entry into U.S. training programs and to get excess military equipment not in use by the U.S. military. That the status also allows access to US financing in grants and loans to purchase weapons is of questionable value, given how Congress has blocked grant financing for the purchase of much-needed aircraft.

Pakistan’s strong rebuke to President Trump’s accusations suggests both Islamabad and Washington may well be on a collision course. Being stuck between a rock and a hard place is never easy, and there are four things that Islamabad can do to avoid being skewered by shrapnel from America’s new Afghanistan policy in the coming days:

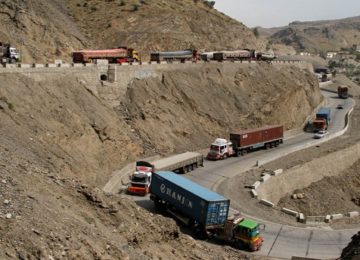

First, despite the growing gulf between the two sides, disengagement is in neither side’s long-term interest. NATO routes and containerized cargo to Afghanistan still run right through Pakistan. The United States also remains the biggest underwriter of security in Afghanistan, and by extension the biggest player in the Afghan equation. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s decreasing exports and growing trade deficit are significant enough to not buffer it from the shock of losing the U.S. export market. These realities notwithstanding, Pakistan’s stance should be clear: that it remains committed to a peaceful and stable Afghanistan. It’s response to coercive measures by Washington, if any, should be graduated and incremental.

Second, Pakistan can look to consolidate the early support that has been offered by Russia, China, and Turkey by additional backing from Tehran and Riyadh. The latter will require deft diplomacy and retooling bilateral relations with both. Pakistan will have to signal to these players that while both the source and solution to the conflict in Afghanistan lies in Afghanistan, Islamabad’s own commitment to ensuring clear, concise and effective counter-terror action against global terrorists including the self-proclaimed Islamic State and Al-Qaeda remains unchanged. Pakistan will also have to pay heed to signals from the recently concluded BRICS summit. Even among Pakistan’s friends, patience for militancy is wearing thin. As a responsible regional player, reining in proscribed terrorist outfits through the National Action Plan should be prioritized. This will create the space for coalition building and help converge the interests of major Eurasian players – Russia, China, and Iran – on supporting Pakistan. In turn, this support will cushion Islamabad and the region from the inevitable fallout of future U.S. policy failures in Afghanistan.

Third, the government in Islamabad, in consultation with the opposition and other national stakeholders, should develop consensus on the contours of future Pakistani-U.S. engagement. This is necessary to ensure civilian-military uniformity on what is Pakistan’s foremost foreign policy challenge in an embattled neighborhood. While the National Security Council meeting in Islamabad in response to Trump’s address was a welcome first step, Pakistan can no longer afford lethargic foreign policymaking made worse by inconsistent signaling. The delay with which Pakistan established contact with the new Trump administration in Washington speaks to the complacency that symbolized Pakistan’s foreign policy outreach for the first four years of the PML-N government. And Islamabad still does not have a full-time lobbyist in Washington to help it curry support. This must change.

Finally, the arrests of Afghan Taliban leaders from Quetta and Karachi, together with Mullah Mansour’s killing have served to deplete Pakistan’s already eroded influence over the core of the insurgency. That said, Pakistan must step up efforts to do what it can with its residual leverage to seek political reconciliation next door. But the limitations here must be telegraphed clearly and unapologetically to Kabul and beyond. As should the fact that the National Unity Government still persistently refuses to fence and patrol its side of the border. Nor can Pakistan allow Afghanistan’s continued support of ethnic irredentism to undermine its own war against terrorism. These messages must be conveyed bluntly, and with Washington on copy. The White House may have bowed down to its generals on Afghanistan, but should still know that bullying Pakistan is as bad an idea as is the new halfway house strategy it thinks will help it win the war.

This article was originally published by Jinnah Institute. Original link.