February 07, 2020

As dissidents are attacked and murdered, critics liken the National Directorate of Security to the brutal intelligence service of the Afghan communists in the 1980s.

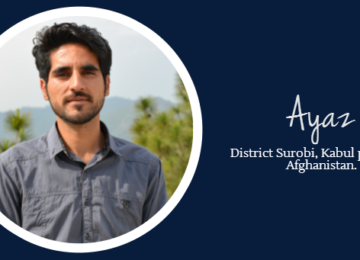

KABUL—When Nazar Mohammad Motmaeen talks about the National Directorate of Security (NDS), the Afghan intelligence service with close ties to the CIA, he becomes nervous. “They are dangerous, and they do not make any compromises,” he said in a recent interview. Motmaeen, a freelance political analyst from Kabul who often appears on TV, says he knows what he is talking about. A few months ago, he says, he was attacked by gunmen in the middle of Kabul. Though he escaped, he later claimed that they belonged to the NDS, which allegedly wanted to silence him because of his political dissent. Motmaeen is a regular critic of America’s military occupation of Afghanistan, and he supports a peace deal with the Taliban.

Motmaeen is hardly alone in telling such tales. A few weeks after the alleged attempt on Motmaeen’s life, Mohammad Hassan Haqyar, another political dissident who regularly criticized the Kabul government, was attacked and injured by unknown gunmen. And on Nov. 20, 2019, Waheed Mozhdah, a senior political analyst and writer, was assassinated in Kabul’s Dar-ul-Aman area after leaving his local mosque. Until today, Mozhdah’s killers remain at large. But he, too, was known for his critical views toward both Kabul and Washington.

Many observers linked pro-government forces to these “chain attacks,” as they have been described by some local Afghan news outlets. “It’s obvious that the government did this or it let it happen,” said Mawlavi Baharuddin Jowzjani, a religious cleric and government critic, on Tolo News, Afghanistan’s biggest news channel. According to family members, Mozhdah was killed by a high-tech pistol. Afghanistan’s whole political landscape reacted to his killing. While government officials claimed that they would investigate the case, the Taliban issued a statement calling the killing an “intelligence operation.”

After Mozhdah’s death, Motmaeen left Afghanistan out of fear. Haqyar also lives abroad at the moment. “The situation in Kabul is not safe for us,” Motmaeen said.

The government has declined to comment on most of the allegations. But NDS director Mohammad Masoom Stanekzai was forced to resign last September after an NDS raid in Jalalabad, the capital of the eastern province of Nangarhar, targeted a prominent local family and killed four brothers, all civilians. While the intelligence service claimed to have attacked alleged members of the Islamic State, locals rejected this version. It was later revealed that all victims were innocent men between 24 and 30 years old who were beaten and shot dead by the infamous 02 unit, which is responsible for similar operations in the eastern region.

Stanekzai used to be part of the Afghan communist regime and fought against the mujahideen in the 1980s. And many Afghans believe that the NDS, with the CIA’s help and approval, has already turned into a second incarnation of KhAD, the brutal intelligence service of the Afghan communists in the 1980s. KhAD killed and tortured tens of thousands of people following the bloody communist coup in 1978. KhAD’s most notorious chief was Mohammad Najibullah, who later became Afghanistan’s last communist president. As the former senior KGB archivist Vasili Mitrokhin noted, Comrade Najib, as he was known, was famous for beating and torturing prisoners to death. Toward the end of his presidency, as the Soviets were preparing to withdraw, Najibullah called for a national reconciliation process with the very people he had spent years torturing. His calls for uniting the fractured nation fell on deaf ears, as millions of Afghans still saw him as a brutal torturer. To this day, many KhAD mass graves have not been located.

According to some people, the NDS is not just the official successor of KhAD—it is also imitating its brutal tactics to turn Afghanistan into a new police state with the help of U.S. intelligence, which is supporting the regime.

All these questions came to a head when, a few weeks after Mozhdah’s killing, Kabul was shattered by another atrocity.

Around 7:30 p.m. on Jan. 5, members of an NDS special forces unit burst into a residential home in one of Kabul’s busiest neighborhoods. By the early morning, five people were dead, killed in cold blood. “They attacked our home in a very brutal manner. It was a slaughter,” one of the witnesses said. One of the victims was Amer Abdul Sattar, a former anti-Soviet commander and noted political figure. Sattar, who lived in nearby Parwan province, had been invited over the weekend to Kabul and was believed to have been the NDS’s primary target that night. His son was also killed in the raid.

Until today, it is not known why the raid took place or why Sattar was killed. It may have even been a mistake: Contrary to other victims, he was a considered a pro-government figure and supported President Ashraf Ghani during his last election campaign in 2019. At the time of the raid, all of the victims were unarmed. “Five people were killed, and two were taken by the NDS. Seven others remained in the house,” Abdul Nasir, a relative of Sattar, told Foreign Policy. According to the witnesses, the NDS unit intended to kill everyone in the apartment.

“Amer Sattar and his son were our guests. They were killed with my father and one of my brothers,” said Shafi Ghorbandi, the son of the homeowner.

But at the same time, it was obvious that the raid against Sattar would shake politics in the capital. “As soon as I heard, I reached out to the president,” Amrullah Saleh, Ghani’s current running mate and a former NDS chief, said at Sattar’s funeral the following day. Saleh was a close friend to Sattar. After the funeral, Ghani welcomed Sattar’s family members at the presidential palace and expressed his condolences. He also promised an investigation of the raid.

The killing of Sattar also became a hotly debated issue in the Afghan parliament, with several legislators demanding a thorough, proper investigation into the raid. The parliament took the opportunity to inquire about the increasing number of night raids that have been happening across the country.

In fact, while the parliament was still discussing the raid in the city of Kabul, there were reports of another night raid, again carried out by the NDS, in the eastern province of Laghman. An elderly man was reportedly killed, and his four sons were taken into NDS detention. In fact, similar incidents have taken place all over the country over the last several months. Nearly every reported incident was said to have involved the NDS and the CIA, which simultaneously maintains its own force while also supporting its Afghan counterparts in the NDS.

In Afghanistan, both intelligence services have become notorious for their hunt-and-kill tactics, which often result in civilian casualties. It is well documented that CIA units like the Khost Protection Force (KPF), which is mainly present in the southeastern provinces, abduct, torture, and kill Afghan civilians deliberately—a fact that was underlined by a Human Rights Watch (HRW) report in late 2019. The 53-page report documents 14 cases across nine provinces from late 2017 to mid-2019. According to HRW, the cases clearly illustrate that the Afghan forces trained and funded by the CIA have shown little concern for civilian life or accountability to international law. The militias are active all over the country, most recently in the provinces of Khost, Paktia, Paktika, Nangarhar, and Maidan Wardak.

“These abusive forces, which are backed by the CIA, have routinely disregarded protections to which civilians and detainees are entitled,” Patricia Gossman, HRW’s associate Asia director and the report’s author, told Foreign Policy. “These are not isolated cases but illustrative of a larger pattern of serious laws-of-war violations—even war crimes—by these paramilitary forces. In case after case, the NDS strike forces and KPF have simply shot people in their custody and consigned entire communities to the terror of abusive night raids and indiscriminate airstrikes. The U.S. and Afghan governments should end this pathology and disband all irregular forces.”

Since transparency does not exist, it often appears unclear how far the NDS is involved in these operations and the control of militias like the KPF. However, the hierarchy appears to be clear, which means that nothing can happen without the CIA’s approval. At the same time, little is known about the NDS, its structures, and to whom it is answering. “Many people who worked with NDS during the last years were communists who also used to work with KhAD. This is not a coincidence,” Motmaeen said. During his lifetime, Mozhdah also claimed that many former communists took over the NDS and imitated KhAD practices to spread fear and terror. While the function of militias like the KPF and its ties to the CIA are obvious—the KPF is being trained and equipped at Camp Chapman, a CIA base in the middle of Khost—the NDS, which is an official organ of Afghanistan’s security apparatus and claims to serve the nation’s interests, is much more ambiguous.

Stanekzai, the former NDS commander, has been succeeded by Ahmad Zia Saraj, who appears to have no clear political background. “Contrary to others, he has a clear intelligence background. But he kept a low profile and worked his way up. At the end, he took over with the blessing of both NDS and CIA,” an Afghan security analyst who requested anonymity told Foreign Policy. Nevertheless, there are rumors that Saraj might lose his position after the raid against Sattar. “He is facing a lot of pressure now. We will see if he will remain on his seat or not,” the analyst said.

But while criticism toward the NDS is growing, incidents like the raid that killed Sattar and his son reveal how confident the intelligence service feels while conducting human rights abuses, even in the middle of Kabul’s urban areas. Sometimes its 01 unit can even be seen in broad daylight in the city.

“There is a strong ‘you are with us or against us’ policy. Any kind of political opposition and dissent is considered as ‘terrorism’ or ‘warlordism’ [by the government]. Afghanistan faced such policies once in its darkest times, and the outcome is well known,” said Saeed Jalal, a Kabul-based researcher and analyst.

Probably the most notorious spy chief in Kabul was Asadullah Khalid, who led the intelligence service from 2012 to 2015. Already before doing so, Khalid was accused of a long list of human rights abuses, including abduction, torture, rape, and murder. In 2010, Canadian government documents reported that Khalid had his own private dungeon while serving as the governor of Kandahar. He was also accused of the murder of five United Nations workers allegedly to protect the local drug trafficking ring in which he was involved. Khalid vanished from the political landscape after he was severely injured by a Taliban attack in December 2012, a few months after he became NDS chief.

In early 2019, Ghani appointed Khalid as defense minister. The step was criticized by several human rights organizations because of Khalid’s brutal past. However, his reinstallment just underlined the path that Kabul’s security regime appears to be taking.

Source: Foreign Policy.