NISP overlooks the fact that internal security is about fixing internal faults, some of which represent a continuous threat to social peace, economic development and cohesion.

The new national security policy (NISP 2018) released recently by former Interior Minister Ahsan Iqbal, is a welcome step insofar as the occasional review and recalibration of policy documents is concerned. It introduces a new regime focused on the 6 ‘Rs’, Reorient, Reimagine, Reconcile, Redistribute, Recognise, and the adoption of a Regional Approach as a recipe for peaceful socio-economic development. The rest is largely a regurgitation of the NISP 2014, masked in somewhat new diction, except the names of nearly all the officials who contributed to it.

Like a typical western report, NISP too points out the Islamic State as the biggest threat to the country and warns against the potential spill over of this brand of terrorism from Afghanistan into Pakistan.

Unfortunately, the NISP 2018 treats various forms of terrorism, including trans-border terrorism, as our most pressing challenge, little alluding to the fact that most manifestations of terrorism — or violent extremism — which has seen marked reduction as a result of hard power and kinetic operations in the last two years — are directly connected with our relations with India and Afghanistan. This terrorism can only be eradicated completely once relations with these nations improve.

NISP overlooks the fact that internal security is about fixing internal faults, some of which represent a continuous threat to social peace, economic development and cohesion.

The biggest fault-line is not extremism, but what must be a source of concern for everybody, and a factor that continues to muddy Pakistan’s name abroad, is increased religiosity and the deployment of faith as a shield to protect people or groups who take the law into their own hands. This includes actions like the recent attack on an Ahmadi place of worship in Sialkot, construction of Mosques and Madaris on state lands without permission and religious congregations without permission in public spaces. This is reflected in our electronic media as well. More and more time is given to so-called Islamic scholars who seem more focused on sensationalism than disseminating any real religious knowledge.

As a whole, the state has failed to stop media houses from using the peoples’ religious sentiments for their own commercial purposes. PEMRA has even failed to enforce the TV channels’ obligation to have 12 minutes of advertisements in every hourly cycle. Often, the additional slots given to these religious preachers are used to propagate objectionable obscurantist ideas. If PEMRA can’t accomplish this much, how can we stop non-state actors from propagating their hateful ideologies?

This is all happening because the ruling political elite are unwilling to act as the first line of defence against the fictional religious narratives which are broadcast by our Mosques and Madaris. Public representatives are supposed to guide and protect their communities against the narratives of non-state actors.

Nowhere does NISP mention this. Nor does this policy underscore the importance of Article 25 (Equal citizenry rights) as the core for maintaining inter-faith harmony. Articles 19,20 and 21 of the constitution too find no mention.

All the rights promised in these articles are core values present in the counter-terror and counter-extremism policies of nearly all Western democracies. Unless the state prioritises these values and treats its citizens equally; internal security and peace will remain at risk.

Resentment among Baloch Pakistanis and the FATA-related grievances recently articulated by the Pakhtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) too represent fault lines that not only constitute a permanent challenge to internal security, but also provide tools to outsiders for stoking trouble inside the country. Security forces have taken corrective measures in FATA, and one would hope that gradual integration will mitigate many other issues that arise out of the absence of normal, community-based policing.

The expedience that led to the Faizabad Agreement, with the signatures of the former interior minister Ahsan Iqbal (after the Federal and Punjab police acted as silent spectators when the Khadim Rizvi brigade blocked the inter-section), or the silence of major parties (except PPP leaders) over the Sialkot incident, simply runs contrary to the ideals laid out in NISP and even NAP. Without autonomy of police, criminal justice system reforms, police reforms, and strict across-the-board enforcement of existing laws (all promised in the National Action Plan) NISP cannot succeed.

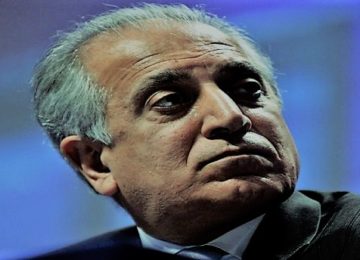

The author Imtiaz Gul is the Executive Director of the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), Islamabad.