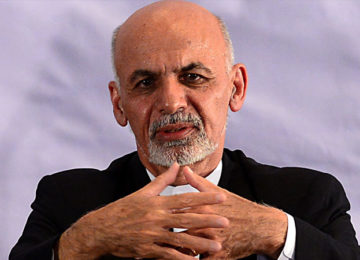

The Afghan President Ashraf Ghani met with General Qamar Javed Bajwa, the head of the Pakistan army, at his palace – Arg – in Kabul on Oct 1. Ghani branded this ice-breaking meeting as a “new season of relationships between Afghanistan and Pakistan” and that both countries should get the most out of the current situation[1]. Such encounters usually trigger hopes and raise expectations for the better. Both agreed to engage for rubbing off mistrust and focus on counter-terrorism.

But this particular meeting begs the question as to whether any of the fundamentals that divide Pakistan, Afghanistan, India and the US have changed at all? And whether stakeholders can really get some thing , if not most, out of it, without any forward movement on those fundamentals?

Context

It would not be out of place to contextualise the Kabul meeting ahead of the arrival (Oct 2) in the US of Pakistan’s foreign minister Khwaja Mohammad Asif for first formal official talks, which are likely to mostly focus on Afghanistan.

The Ghani-Bajwa meeting took place to the a week after Pakistani Prime Minister Shahid Khaqaan Abbasi’s terse encounter with vice president Mike Pence meeting in Washington,[2] last week, and US Defence Secretary James Mattis’s latest talks in New Delhi with Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman.

Although, according to a Pakistan’s Foreign Office statement, both sides “ agreed that the two countries would stay engaged with a constructive approach to achieve shared objectives of peace, stability and economic prosperity in the region,” yet there was more than met the eyes.

Both – Abbasi’s meeting with Pence as well his interactions elsewhere were a sort of “hard talk,” an assertive Pakistani perspective on issues such as Afghanistan and India. It certainly laid bare the faultlines that already exist in the tempestuous bilateral relations.[3]

As expected, Abbasi regurgitated Pakistan’s counter-terrorism efforts and also recalled that the country suffered huge losses as tens of thousands of US-NATO cargo containers rolled through its territory. But we never charged the US-NATO for the use of our aerial and ground lines of communications (ALOCs, GLOCs), he told Pence.[4]

Fundamental Irreconcilables

All the latest contacts at the highest level notwithstanding, forward movement would possibly depend on how these countries deal with some fundamental “irreconcilables” that inhibit the path to a constructive dialogue.

The US administration, for instance, still holds Pakistan solely responsible for its as well as President Ghani’s woes in Afghanistan. They also believe Pakistan is the key both to the Taliban’s continued resistance and their participation in the peace talks.

And this is premised in Pakistan’s perceived leverage with the Taliban as well as its refrain from an all-out war against Taliban allegedly living in Pakistan itself. The last 15 years or so, this narrative has remained irreconcilable as far as Washington and Kabul are concerned.

Pakistan, on the other hand, is driven by its own several non-negotiable constants;

Firstly, while continuing its crackdown against all non state actors as part of its counter-terrorism campaign, it will never wage war against Afghan Taliban on its soil. For turning the back on all Afghan factions, it needs political space within the country, which the new Indo-US resolve on CT cooperation in Afghanistan threatens to restrict further. No country easily gives up on what it considers its strategic interests. Outsiders shall also have to understand that peace in Afghanistan, at the same time, has never been in the hands of Pakistan. Old relationships with mujahideen, Hamid Karzai, Professor Rabbani (late) Prof Sayyaf, Mulla Omar and several Taliban/Haqqani leaders notwithstanding, its leverage has shrunken considerably.

This is tied to the second constant i.e. peace in Afghanistan; instability and continuous state of conflict there has affected Pakistan like no other country and it drives the consensus both in Islamabad and Rawalpindi, the seat of the might military establishment, that without secession of violence in Afghanistan, Pakistan too will remain embroiled in the crisis of insecurity. And hence the urgency for resumption of intra-Afghan peace and Pak-Afghan bilateral talks.

Islamabad and Rawalpindi, i.e. General Headquarters, alone cannot determine the course of peace and conflict any more; its first of all in the hands of the Kabul ruling elites who must develop consensus on a) how to deal with Taliban and b) determine what to realistically expect of Pakistan in the maze of genuine insurgency, external proxies and organised crime, factors that have continued to feed insurgency and obscured the real actors behind the violence.

The third non-negotiable too is related to Afghanistan i.e. the Indian factor in the conflict-battered country; Defence Secretary Mattis’s New Delhi visit (Sep 25-27) and agreements reached with Defence Minister Nirmala Sitharaman for enhanced Indian role in the training of Afghan police and soldiers in the counter-terrorism. It remains a big worry as well irreconcilable as far as Pakistan’s might military establishment is concerned.

If the US is not inclined to demonstrably use its leverage with India for a matter-of-fact dialogue with Pakistan, then it would entail all sorts of suspicions and hold the Pakistani interlocutors back. Instead it would breed scepticism on the motives of the US-India partnership in Afghanistan.

Pak-China relations is the fourth irreconcilable constant for Pakistan; given the long history of cooperation and with the obvious Indian dislike for the Pak-China Economic Corridor (CPEC), Islamabad will never step back from Beijing, something that both India and US desire as a prerequisite for a more favourable treatment of Pakistan.

The fifth irreconcilable constant is Pakistan’s nuclear programme, which no body, the security establishment in particular, would dare think of decelerating, freezing or abandoning altogether.

From a strategic point of view, the security establishment and the civilians alike look at Afghanistan, relations with China and the nuclear programme as a matter of life and death and existential lifelines. Any compromise would be akin to severing these perceived life lines.

Pakistan simply cannot afford both geo-politically as well as morally to walk away from China in the present critical circumstances. Nor will it be comfortable with countries such as the US to look at it through the Afghan prism.

A substantive convergence and progress in the Pak-US and Pak-Afghan ties will only be possible if these countries re-tweak their constant non-negotiable fundamentals. They have to find a middle ground to be able to synchronise thought and action in Afghanistan.

——–

[3] Author’s discussions with diplomatic officials in Washington

[4] Author’s discussions with diplomatic officials in Washington

The writer Imtiaz Gul is the Executive Director at the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), Islamabad.

© Copyright Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS) and Afghan Studies Center (ASC), Islamabad.