Pakistan’s general election on July 25 is poised to be a transformative moment for the nuclear-armed country, as it continues to deal with the fallout of the arrest and conviction of former leader Nawaz Sharif on corruption charges.

Tensions are running high amid deadly terrorist attacks, arrests media censorship and accusations of interference by the military.

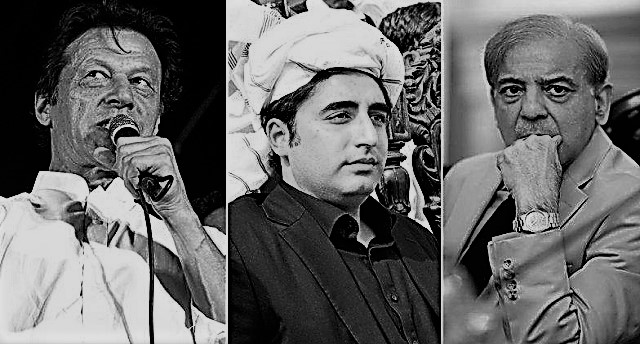

As campaigning enters the final stretch, charismatic populist and former cricket star Imran Khan and the deposed leader’s brother, Shahbaz Sharif, have emerged as the two frontrunners.

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, the 29-year-old son of former leader Benazir Bhutto, is also attracting widespread support, seeking to reestablish his family’s party as a viable political force.

Polls suggest the race is too close to call, and could result in coalition negotiations which leave Bhutto Zardari’s smaller party with the balance of power.

So just who are the men vying to by Pakistan’s next Prime Minister?

Imran Khan, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) Justice Party

Politicians the world over would kill for the name recognition that Imran Khan has.

Arguably one of the best cricket all-rounders in the history of the game — skilled at both batting and bowling — he dominated the crease throughout the 1980s, culminating in helping a struggling Pakistan national side to the World Cup title in 1992.

In a nation obsessed with the sport, the 65-year-old has cleverly engineered his legendary status to transition into a career in politics.

He’s the leader of the center-right Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), otherwise known as the Justice Party, and has adopted a hardline, religious persona to appeal to a wide base of voters, according to Mosharaf Zaidi, a newspaper columnist and political analyst.

While PTI has seen some success at the provincial level, analysts said Khan remains a policy lightweight. Journalist and author Zahid Hussain said the former cricketer has “never had a serious political philosophy.”

Khan has been a figure — though not a force — in Pakistani politics since the late 1990s, but Zaidi said his populism has “never been quite so effective or successful as today,” owing in a surge in support from Pakistan’s “angry (and) disenchanted” middle classes.

“He’s one of the drivers of restrictions of the press, he publicly feuds and attacks newspapers and journalists. He doesn’t stand for freedom unless that press freedom entails praising Imran Khan,” Zaidi added.

Khan is perceived to be the preferred candidate of the country’s powerful military, which has directly ruled the country for almost half of its independent existence since 1947, and has maintained an outsized influence over politics throughout that period.

The country is divided into two camps, said journalist and former Pakistani ambassador to the US Husain Haqqani, those “who think the military has a right to run the country,” and those who don’t. A lot of the former have rallied to Khan, he said.

“The groups that benefited from military rule, they don’t like the political class that share this power,” Haqqani said, adding some of the military and their offspring feel marginalized. “Their disaffection is with democracy. (Khan is a) pro-establishment populist, not an anti-establishment populist.”

Khan has also benefited from the military’s antipathy to his former political rival, Nawaz Sharif, who was recently sentenced to 10 years in prison on graft charges.

The PTI has been able to capitalize on Sharif’s downfall, and Khan has campaigned hard on anti-corruption issues.

This issue has “become the most effective tool in his political arsenal,” Zaidi said. “It goes beyond a rhetorical instrument.”

However, while Khan is seen to be clean, some of his associates and political allies “are accused of the same scams and corruption that he accuses his rivals of,” Zaidi added.

Haqqani, the former ambassador, said Khan’s record until now isn’t necessarily proof of incorruptability: “He has never been in government, how do we know he’s clean?”

Shabahz Sharif, Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N)

Khan’s biggest rival in next week’s election is Shahbaz Sharif, long the crown prince of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML) and once considered the natural successor to the leadership.

Despite his brother Nawaz Sharif’s conviction and jailing, the family still garners considerable support.

In fact, that case may have advanced Shahbaz’s political standing.

Nawaz had previously shifted favor to his daughter, Maryam Sharif. However, she was also caught up in the corruption scandal and now sits alongside her father in prison, reopening the path for Shahbaz.

Pakistani Taliban claims responsibility for deadly election suicide attack

Haqqani said the electorate is divided over the Sharifs: “some think the entire family is crooked; some think that they’re crooked but deserve due process; then there’s some who say: ‘we don’t care — they’re our people’.”

But he added Shahbaz is “very much of the political machine that he and his brother built together.”

Chief minister of Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province and a key electoral battleground, Shahbaz’s credentials and successes as an administrator could serve him well, according to Zaidi, the journalist.

“Punjab’s overall infrastructure and development is superior to other provinces, and this is part due to his governance,” he said.

In fact, Shahbaz may have the opposite problem to Khan, said Haqqani, in that he is more of an administrator than a politician, and lacks the charisma and flair of his rival or brother.

Nawaz and Maryam’s dramatic return to Pakistan from London, where they were caring for Nawaz’ terminally ill wife Kulsoom Nawaz, to face conviction “will shore up a degree of empathy among the electorate,” Zaidi predicted.

“It’s certainly demonstrated that (the Sharif family) is not going away without a fight,” he said.

While Shahbaz remained separate from the corruption scandal which ensnared his brother and niece, there’s still a taint by association, said Zaidi.

“He doesn’t seem to be in the exact same box as Nawaz … but he’s certainly not immune from accusations of corruption,” he said.

“If he were to emerge as a national leader he would be hounded by those accusations. The people who were going to vote on the basis of corruption aren’t going to vote for a Sharif anyway.”

All this has led to an erosion of support, even in Punjab, a former PML-N heartland into which the “PTI has made stunning inroads,” Zaidi said.

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, Pakistan People’s Party (PPP)

The son of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto — the first woman to lead a Muslim nation, who was assassinated in 2007 — and former President Asif Ali Zardari — the only elected Pakistani president ever to have completed a full term in office — 29-year-old Bilawal is unlikely to cause an upset in the two-horse race between the PML-N and the PTI.

He comes from PPP stock that is reasonably pragmatic, multilateralist and internationalist, said Zaidi, and the Bhutto name still has a lot of currency, particularly in the family’s heartland in southern Sindh province.

Success in this month’s vote could see him revive the fortunes of the PPP, which suffered during his father’s tenure, though the elder Zardari remains a co-leader of the party.

Haqqani, who is close to the Bhutto Zardari family, said Bilawal is “running for the election after this election.”

“He’s said nothing negative about anybody, (while) putting out the most praised manifesto, most elaborate document on what Pakistan needs in policy terms,” he said. “He’s reached out to his mother’s support base, bringing them back — (the PPP had) lost support after his father’s stint as president. He’s still young, he’s in no hurry and he’s showing that.”

Hussain, the journalist, says Bilawal was moving out of his parents’ shadow, “presenting himself as a mature and sober (figure with) potential to revive the party.”

While it’s unlikely the PPP could win an outright majority, a strong showing by the party could leave Bilawal in the position of kingmaker for future coalition negotiations.

In the event of a hung parliament, his father is likely to push for a partnership with either of the opposition parties, though Bilawal may be less keen to be a junior partner.

The younger politician “will probably not want to go along with either of the two major parties right now if he wants to stake a claim to principle,” Haqqani said. “But his father is still a political creature … (Zardari) wouldn’t mind forming a coalition with either party, based on what his party can achieve in a pragmatic sense.”

This article originally appeared on CNN on July 20, 2018. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.