The US Under Secretary of State Alice Wells, In a recent interview with the Voice of America, made a surprising reference to Pakistan and its interests in Afghanistan: “I believe that Pakistan’s strategic interests are going to be served by a stable and peaceful Afghanistan and so how do we work together to achieve a stable and peaceful Afghanistan. … what is of our overriding priority in the region which is stabilising Afghanistan”, said Wells.

The question that arises here is if the US and its allies pursue their interests — often to the disregard of issues such as sovereignty and international human rights charter — why should they have an issue with Pakistan pursuing its own strategic interests?

This is a theme that has possibly evolved ever since Richard Olson, US Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, began peddling it since his retirement early this year, and thus became the talk of the town in Af-Pak policy. “Pakistan considers the Afghan Taliban as its ‘core strategic asset’ and thus unlikely to abandon them. … for the Pakistani establishment, the Afghanistan policy is “about geo-strategic manoeuvring against India,” Olson had said in April during a talk on Afghanistan and Pakistan at the Stimson Institute in Washington.

Interestingly, this realisation or the acknowledgement of it has been missing in Washington all these years. Inherent in the “do-more or face consequences” mantra is the US monopoly over decision-making, both for itself and others — all in the name of national interests. This propensity essentially disregards other nation’s right to take decisions for them. And thus results in occasional frictions with other countries. This situation This has also defined the Pak-US relationship in since the traumatic 9/11 terrorist attacks, and obstructed a logically understandable conversation on peace in Afghanistan.

That is why the uproar and wave of concern in the aftermath of the Trump Strategy unveiled in August. But as the dust settled down, it made way for a more pragmatic approach, with saner voices emerging in both capitals.

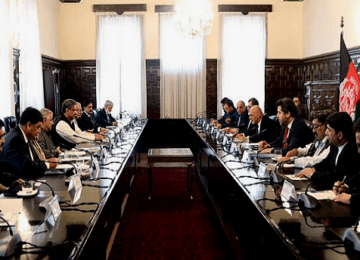

National Security Advisor, General (R) Nasir Janjua, for instance, set the ball rolling for such a conversation, when he delivered a straight message to the US ambassador Alex Hale in a meeting on August 23. Janjua underscored the need for all stakeholders to seek closure of the Afghan conflict. For him, Pakistan’s challenges are manifold when trying “not to remain singled out as a source of violence in Afghanistan” as well as stop being looked at through the Afghan and Indian prism.

He is also of the view that Pakistan is ready to cooperate without compromising major national interests. This, he believes, should accompany a pro-active engagement with all to explain national interests and the rationale for policies.

All stakeholders must seek closure of the Afghan conflict. The Taliban card ought to be handled cautiously. Pakistan has lost most of its leverage over Afghan Taliban. Most of the field commanders are on their own, and are based inside Afghanistan

At the same time, all stakeholders must seek closure of the Afghan conflict as much as possible but it must be cautious in handling the Taliban card. It has lost most of its leverage over Afghan Taliban. Most of the field commanders are on their own and inside Afghanistan. Translating this approach into a coherent whole-of-government approach, nevertheless, represents a formidable challenge that Pakistani civil-military leaders have yet to stand upto. It requires extreme caution and measured responses, say in media interviews.

Coherence of policy and coordination of action also necessitates a nationalistic, though rational approach instead of the usual wrangling and score-settling by some ministers witnessed in recent weeks. They clearly either forget or wilfully ignore that by apportioning blame — direct or otherwise — on one or the other institutions, they only add complications; with motivated statements they not only create more difficulties for themselves as members of a government but also sullying the image of the country.

The latest revelations in a Hindustan Times article, which essentially admits a nexus between the Indian security establishment and the TTP reflect the National Security Advisor Ajit Doval’s ‘contain Pakistan’ doctrine, should enforce lot of reflection in Islamabad’s power houses. Doval believes in keeping Pakistan under check through TTP as well as a counter to Jaish’s and Lashkars. And this also exposes the nature and cause of violence across Pakistan; since its driver is external, its dimension are often either sectarian, Baloch nationalist, or direct attacks on police or other organs of the security apparatus. For outsiders, this remains Pakistan’s internal war, overlooking the plain fact that this war stems from the way the present Indian leadership looks at Pakistan. It achieves two major objectives; it creates panic, scare and uncertainty inside the country with the aim of demoralising the security forces. Secondly, it provides New Delhi and its information machinery to flag Pakistan as a violence-torn country, and thus unworthy of any partnership.

Herein lies the challenge for all nationalist Pakistanis; the civilian and military ruling elites must chalk out a collective response to the Indian narrative as well as strategic communications’ strategy to;

Firstly, explain the causes by relating the violence to what India thinks and does as far as Pakistan is concerned. India clearly is trying to pin Pakistan down in domestic conflicts, and itself expand its influence and trade with Asia-Pacific and the rest of the world.

This is an uphill though inescapable task because most outsiders do look at our country through the Indian prism

Secondly, deflect the negative perception through a well-crafted, Pakistan-centric narrative that only looks at the positives of the country instead of always relating to India or Afghanistan.

Thirdly, engage and benefit from China’s domestic and foreign policy approach which is built on self-respect, confidence and indigenous prioritisation of issues. We need to sequence our steps in our own way. As a responsible member of the global community, Islamabad should also address external concerns about the Haqqanis, Jaishs and Lashkars.

And lastly, to deal with an enemy (TTP) that has slipped into shelters across the border and is being used as a proxy against Pakistani interests. Denying them social support and space inside Pakistan through mosques and seminaries with elaborate and coordinated security operations must remain a priority.

The author Imtiaz Gul is the Executive Director of the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), Islamabad.