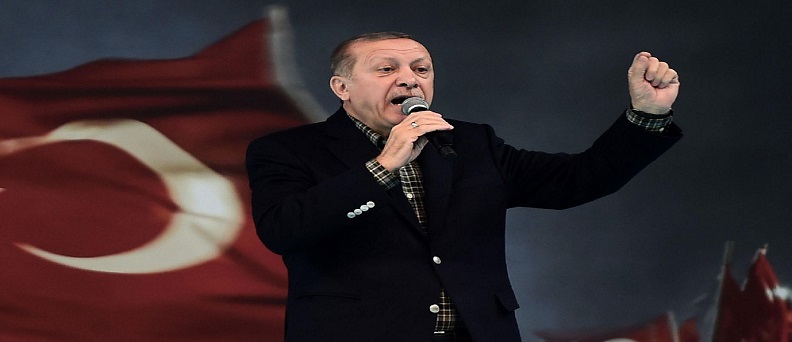

Of late a number of Pakistani politicians and experts—either motivated, confused, ignorant or blind believers in personalities—drew comparisons between Turkey and Pakistan, stretching them as far as to equate ousted prime minister Nawaz Sharif with President Recep Tayyab Erdogan. These comparisons amounted to a travesty given the ground realities in the two countries. The inherent mistake in these comparisons is that Pakistan is not Turkey, nor can Nawaz Sharif replicate what Erdogan has done to Turkey—although both Sharifs seem to eulogise the latter as their role model, perhaps not so much for Erdogan’s Islamist zeal as for his political and business expedience.

Consider this. Professor Behlül Özkan of Marmara University, Istanbul sums up the Turkish political landscape in a paper for the Hudson Institute: The rule of law has been suspended in Turkey, corporations have been taken over by the government, pro-AKP (the ruling party) trustees have been appointed as mayors in numerous municipalities, opposition politicians and journalists have been arrested, and the country as a whole has become increasingly authoritarian as it leaves the orbit of the EU. There is no doubt… that the Turkish Islamism, which rose to prominence in Cold War-era Turkey as part of the struggle against an ascendant Left, is now transforming a secular democratic republic into an authoritarian far-right Islamic polity, in line with its own world view.

Not surprising, according to the Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, that since the failed coup attempt a year ago, over 100,000 public officials and civil servants including around 28,000 teachers alleged supporters/followers of Fatehullah Gülen have been dismissed, suspended or placed under pretrial detention. At least 2,200 judges and prosecutors have been jailed for being Guelenists and with 3,400 permanently dismissed for the same reason, their assets frozen, over one-fifth of Turkey’s judiciary has been removed. Around 11,000 teachers in the southeast, mainly members of the left-leaning E?itim Sen trade union, are also suspended.

As the opposition Kemalist party CHP has struggled for unity and to recapture popular support in the last 15 years or so, the AKP’s retaliation against, and the purge of, the military and judiciary plus bureaucracy actually began in 2008. Erdogan did it on the heels of economic consolidation, with the support not only of Turkish Islamists but also the EU and the US, who viewed the AKP as a “proponent of a well-integrated and global market economy,” which in their view was also working for a democratic transformation.

The Turkish authorities have also been relentlessly following perceived Guelenists and socialist journalists. At least 150 journalists are currently in jails. One of the veteran journalists and rights activists, Murat Çelikkan, for example, began on August 15 to serve an 18-month prison sentence on charges of “propagandizing for a terrorist organization” for the contents of shuttered daily newspaper Özgür Gündem on the day on which he symbolically acted as the newspaper’s co-editor to protest the persistent judicial harassment of the newspaper and its staff. Journalists, academics and officials sympathetic to the Kurdish communist party PKK are also under intense scrutiny, and are often treated as terrorists. Erdogan has emasculated and muzzled the entire press and confiscated properties, papers, TV channels of the opposition Zaman group. Most of the writers of the pro-Gülen group escaped the country.

The AKP is also involved in massive social engineering through schools. Now almost every state school is being redesigned along the Imam Hatip school model, created after the abolition of madaris. Hatip high schools were founded in 1924 to train government employed Imams and raise good Muslims. Most of the public sector schools are now being placed under the Imam Hatip system with an ever increasing emphasis on Turkishness and religiosity, where Arabic lessons are also compulsory.

With Erdogan openly saying that every children should be religious, Turkey today finds itself in the clutches of a self-serving “Islamofascist dictator (as a female journalist put it) who exploits every faultline within Turkey – nationalism, Islamism, and the ethnic conflicts with the Kurds.”

Erdogan, critics say, is a political bigot, who routinely accuses westerners but begs them the next day for financial or political help. General Ziaul Haq welcomed Afghan refugees and the creation of parties such as the MQM. Erdogan did the same by striking a 3 billion Euro deal with Germany to hold Syrian refugees back in Turkey, as they may one day become his voters.

What is common

Erdogan and the Sharifs have certain things in common though. They love privatization of national assets. Erdogan, according to a journalist, “sold almost every valuable assets of the Turkish Republic… created a fund called ‘Turkey Wealth Fund’… and sold our biggest companies’ lands to the Qataris.” Qatar surfaced here not only through the Qatari letter (on Nawaz Sharif’s supposed London flats) but also for the multi-billion dollar LNG contract.

Saudi Arabia is the third common factor. The Saudis own huge business stakes in Turkey. Visiting Saudi Arabia in 2010 as PM, Erdogan had declared, “whatever the EU is to us, Saudi Arabia is too.” Nonetheless, in the seven years since that time, Riyadh has achieved far more cordial ties with Ankara than Brussels has. Turkey created the Jaish al-Fatah (Army of Conquest) in Syria in partnership with Saudi Arabia. Turkey also partnered with Jaish al-Islam (Army of Islam) in Syria under Saudi leadership, and in February 2016, Saudi fighter jets were deployed to ?ncirlik Air Base. The Sharifs owe their own gratitude to the Saudi royal family and in fact their journey from rags to riches in exile – the Azizia Mill’s transformation into Avenfield Flats – is also rooted in Saudi Arabia itself.

Sharif and Erdogan despise opposition. While Erdogan has managed to keep his opponents, political and military, divided through his Machiavellian tactics, Nawaz Sharif cannot hope to surmount the entire civilian and military opposition in Pakistan and neither can he hope to tame the judiciary or media-civil society the Erdogan way.

Another common bond between Sharif and Erdogan is their penchant for crony capitalism and the deployment of faith as an instrument for political objectives. Both have invested heavily in their constituencies through nepotism and patronage. In Turkey, the opposition CHP offers no real challenge or alternative. Here in Pakistan, the PTI remains potent as an untested third political force and its anti-Sharif politics converges with that of the other opposition party, the PPP under Bilawal Zardari.

Political expedience and hypocrisy is probably another common trait. Bitten by the Panama verdict, Sharif now speaks of a revolution, something that is quite contrary to his living standard and style of governance. Erdogan has probably been a little more candid on the means to power; in a 1993 interview, when he was serving as the Istanbul chairman of the Welfare Party, he famously stated: “We hold that democracy is only a vehicle. It is a vehicle to choose whatever system you wish to arrive at.” This, in essence, legitimized democracy as a tool to absolute power. If this sounds like the 13thAmendment that Sharif had attempted during his second tenure, you would not be wrong in thinking so. That would have turned him into a despot in the guise of a democratic leader, former law minister Iftikhar Gilani once said while recalling a meeting with the Sharifs along with Asfandyar Wali Khan.

In short, don’t equate Sharif with Erdogan because Pakistan is not present-day Turkey.

The author Imtiaz Gul is the Executive Director of the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS), Islamabad.