A high-stakes plan to indict Afghan drug lords and insurgency leaders on criminal conspiracy charges ran afoul of the Obama team. Five years later, it remains buried under Trump.

As Afghanistan edged ever closer to becoming a narco-state five years ago, a team of veteran U.S. officials in Kabul presented the Obama administration with a detailed plan to use U.S. courts to prosecute the Taliban commanders and allied drug lords who supplied more than 90 percent of the world’s heroin — including a growing amount fueling the nascent opioid crisis in the United States.

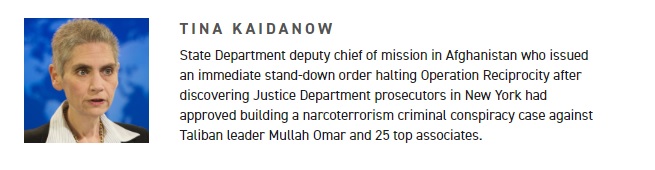

The plan, according to its authors, was both a way of halting the ruinous spread of narcotics around the world and a new — and urgent — approach to confronting ongoing frustrations with the Taliban, whose drug profits were financing the growing insurgency and killing American troops. But the Obama administration’s deputy chief of mission in Kabul, citing political concerns, ordered the plan to be shelved, according to a POLITICO investigation.

Now, its authors — Drug Enforcement Administration agents and Justice Department legal advisers at the time — are expressing anger over the decision, and hope that the Trump administration, which has followed a path similar to former President Barack Obama’s in Afghanistan, will eventually adopt the plan as part of its evolving strategy.

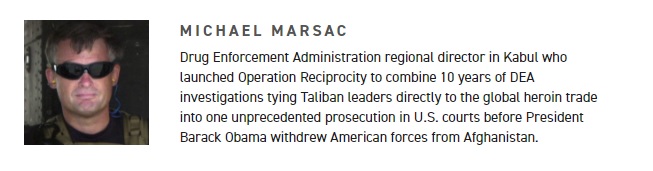

“This was the most effective and sustainable tool we had for disrupting and dismantling Afghan drug trafficking organizations and separating them from the Taliban,” said Michael Marsac, the main architect of the plan as the DEA’s regional director for South West Asia at the time. “But it lies dormant, buried in an obscure file room, all but forgotten.”

A senior Afghan security official, M. Ashraf Haidari, also expressed anger at the Obama administration when told about how the U.S. effort to indict Taliban narcotics kingpins was stopped dead in its tracks 16 months after it began.

“It brought us almost to the breaking point, put our elections into a time of crisis, and then our economy almost collapsed,” Haidari said of the drug money funding the Taliban. “If that [operation] had continued, we wouldn’t have had this massive increase in production and cultivation as we do now.”

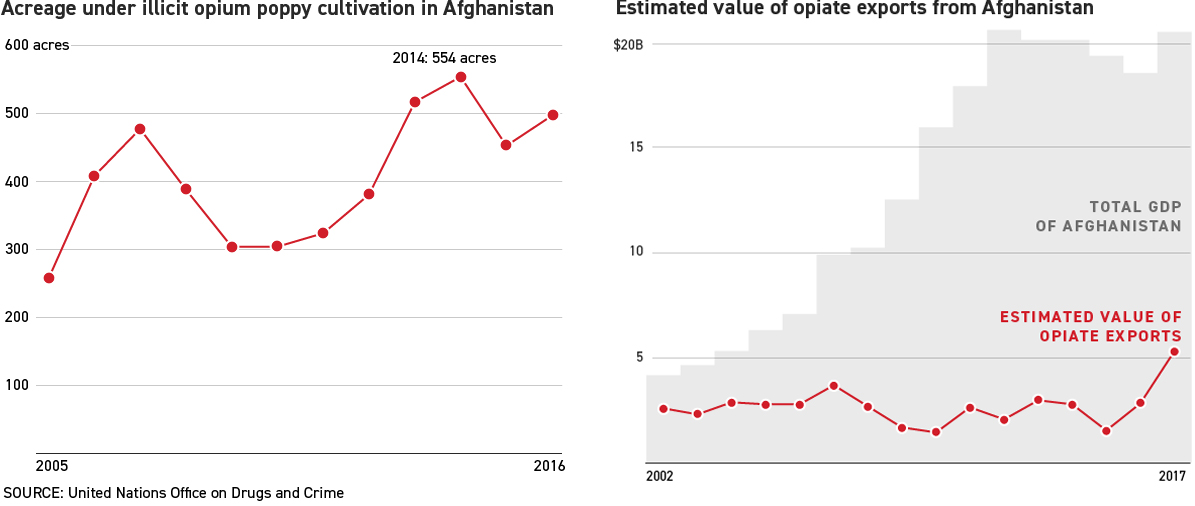

Poppy cultivation, heroin production, terrorist attacks and territory controlled by the Taliban are now at or near record highs. President Ashraf Ghani said recently that Afghanistan’s military — and the government itself — would be in danger of imminent collapse, perhaps within days, if U.S. assistance stops.

But while President Donald Trump has sharply criticized Obama’s approach in Afghanistan, his team is using a similar one, including a troop surge last year and possibly another, and, recently, a willingness to engage in peace talks with the Taliban.

“We have the ability to take these folks out,” he said. “Here’s your road map, guys. All you need to do is dust it off and it’s ready to go.”

The plan, code-named Operation Reciprocity, was modeled after a legal strategy that the Justice Department began using a decade earlier against the cocaine-funded leftist FARC guerrillas in Colombia, in concert with military and diplomatic efforts. The new operation’s goal was to haul 26 suspects from Afghanistan to the same New York courthouse where FARC leaders were prosecuted, turn them against each other and the broader insurgency, convict them on conspiracy charges and lock them away.

In Afghanistan, though, there was exponentially more at stake in what had become America’s longest war — and the clock was ticking.

By the time that plans for Operation Reciprocity reached fruition, in May 2013, the conflict had cost U.S. taxpayers at least $686 billion. More than 2,000 American soldiers had given their lives for it. And the Obama administration already had announced it would withdraw almost entirely by the following year. Like the Bush White House before it, it had concluded that neither its military force nor nuanced nation-building could uproot an insurgency that was financed by deeply entrenched criminal networks that also had corrupted the Afghan government to its core.

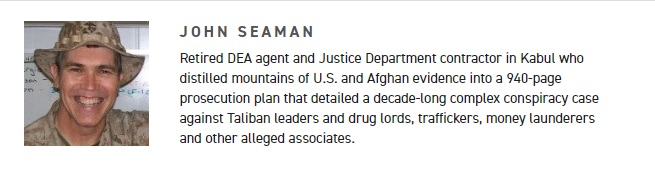

“We looked at this as the best, if not the only way, of preventing Afghanistan from becoming a narco-state,” said Seaman, referring to the government’s term for a country whose economy is dependent on the illegal drug trade. He described Operation Reciprocity as a fast, cost-effective and proven way of crippling the insurgency — akin to severing its head from its body — before the U.S. handed over operations to the Afghan government. “Without it,” he said, “they didn’t have a chance.”

The document — a 240-page draft prosecution memo and 700 pages of supporting evidence — was the result of 10 years of DEA investigations done in conjunction with U.S. and allied military forces, working with embassy legal advisers from the departments of Justice and State. In May 2013, it was endorsed by the top Justice Department official in Kabul, who recommended it be sent to DOJ’s specialized Terrorism and International Narcotics unit in Manhattan. After agents flew in from Kabul for a three-hour briefing, the unit enthusiastically accepted the case and assigned one of its best and most experienced prosecutors to spearhead it.

“These are the most worthy of targets to pursue,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Adam Fee, who had successfully prosecuted some of the FARC cases, wrote in an email to Seaman.

But before Fee could pack for his first trip to Afghanistan, Operation Reciprocity was shut down.

Its demise was not instantaneous. But the most significant blow, by far, came on May 27, 2013, when the then-deputy chief of mission, Ambassador Tina Kaidanow, summoned Marsac and two top embassy officials supporting the plan to her office, and issued an immediate stand-down order.

In an interview, Kaidanow — currently the State Department‘s principal deputy assistant secretary for political-military affairs — said she didn’t recall details of the meeting or the specifics of the plan. But she confirmed that she felt blindsided by such a politically sensitive and ambitious effort and the traction it had received at Justice. If she did issue such an order, she said, it was because she — as the administration’s “eyes” in Afghanistan — had concerns it would undermine the White House’s broader strategy in Afghanistan, including a drawdown that included the DEA as well as the military.

And the White House’s overriding priority ahead of the drawdown, she told POLITICO, was to use all tools at its disposal “to try and find a way to promote lasting stability in Afghanistan,” with peace talks integral to that effort. “So the bottom line is it had to be factored into whatever else was going on,” she said of the Taliban indictment plan. “We look at that entire array of considerations and think, you know, does it make sense in the moment? Does it make sense later on? Does it makes sense at all?”

Its authors counter that Operation Reciprocity was designed in accordance with that White House strategy, an assertion backed up by interviews with current and former officials familiar with it and a review of government documents and congressional records. The authors believe the real reason it was shut down was fears it would jeopardize the administration’s efforts to engage the Taliban in peace talks and still-secret prisoner swap negotiations involving U.S. Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl. They tried to revive the effort after Kaidanow transferred back to Washington that fall, but by then, they say, circumstances had changed and the project never gained traction again.

Recently, Seaman came forward to say that he and his former colleagues had all but given up on Operation Reciprocity until they discovered that the Trump administration had established a special task force to review and resurrect Hezbollah drug trafficking cases after a POLITICO report disclosed that they were derailed by the Obama administration’s determination to secure a nuclear deal with Iran.

The Afghanistan team members said there are striking parallels between their case and Project Cassandra, the DEA code name for the Hezbollah investigations, as well as nuclear trafficking cases disclosed in another POLITICO report as being derailed because of the Iran deal. Taken together, they said, the cases show a troubling pattern of thwarting international law-enforcement efforts to the overall detriment of U.S. national security.

Now they are hoping the Trump administration will review and revive Operation Reciprocity, too, saying Trump’s Afghanistan strategy cannot succeed without also incorporating an international law enforcement effort targeting the drug trade that helps keep the Taliban in business.

Besides helping the military take strategic leaders off the battlefield, they said, it could provide much-needed leverage to finally bring the militant group to the negotiating table and also break up the criminal patronage networks undermining the Kabul government.

For now, though, the plan remains buried in DEA files, and even most agency leadership is unaware of it, several current and former agency officials said. “I don’t think a lot of people even know that we did this, that this plan is in existence and is a viable thing that can be resurrected and completed,” said Marsac, whose eight years in and around Afghanistan for the DEA make him one of the longest-serving Americans there during the war.

Such an undertaking would involve serious logistical challenges to capture drug lords and prosecute them in the United States, not to mention the destabilizing effect on the Afghan economy, from farmers who grow poppies to corrupt government officials accustomed to bribes.

“We’ve made a deal with the devil on many occasions, in an effort not to antagonize anybody and kick the can down the road,” Marsac said. “But you’ve got to cut that off. It might be painful at first, but it has to be confronted.”

Haidari, the director-general of Policy and Strategy for Afghanistan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, agrees and says it is something his country cannot yet do entirely on its own. Haidari recently helped lead a summit meeting in Kabul of 23 countries, including the United States, in proposing another round of peace talks with the Taliban as well as more military aid. Last month, Afghanistan had its first official cease fire since the insurgency began, but it lasted only three days — and demands that the Taliban get out of the narcotics trafficking business weren’t among the conditions.

Haidari said the missing ingredient in the current scenario is a robust U.S. law enforcement effort to help Afghanistan starve the insurgency by attacking the Taliban’s drug funding, which, he noted, was precisely what Operation Reciprocity was designed to do.

“That much money automatically involves their leadership and shows that they are narco-terrorists. You have to go after them,” even if peace talks are also pursued, Haidari said. “If you want to make peace with them, and you discontinue going after them, then the DEA is no longer allowed to do what it needs to do. And that is exactly what happened.”

The alliance of the kingpins

Obama was upbeat in his June 2011 address announcing a gradual end to the U.S. war in Afghanistan, saying, ”We’re starting this drawdown from a position of strength.” The rugged country that once provided Al Qaeda its haven no longer represented the same terrorist threat to the American people, Obama said, and U.S. and coalition forces had thwarted the insurgency’s momentum.

The DEA’s Marsac believed from his many years in country that the situation on the ground wasn’t nearly as stable as Obama suggested. And that things were getting worse, not better.

Obama was correct that most of Al Qaeda’s remaining forces had left for neighboring Pakistan. But Taliban-controlled territory was now home to at least a dozen other terrorist groups with international aspirations. The Taliban itself had evolved, too, from an insular group without animus toward the United States into a lethal narco-terrorist army waging war against the American forces that had deposed it for its indirect role in the 9/11 attacks.

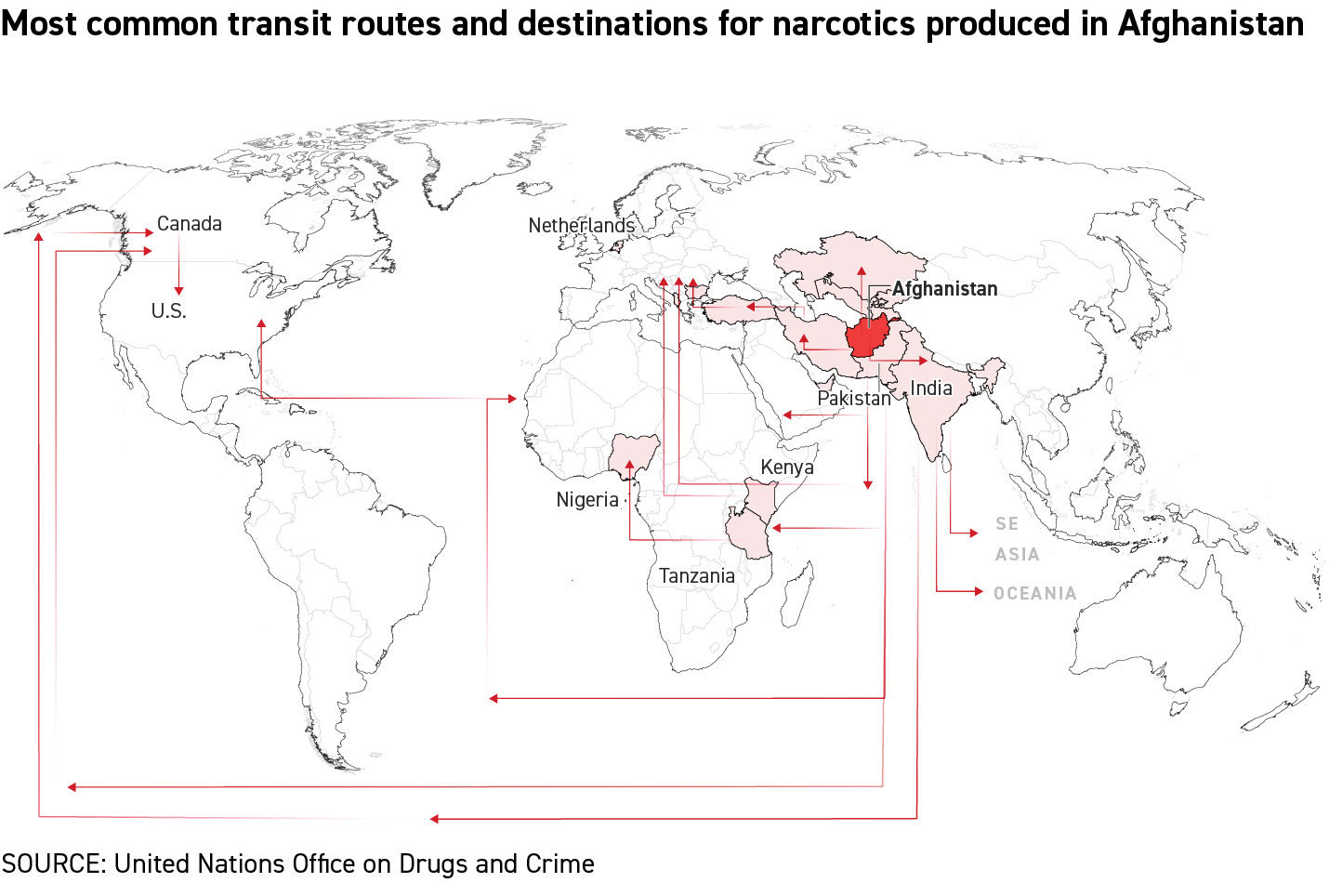

To finance its insurgency, the Taliban was reaping anywhere from $100 million to $350 million a year from its cut of the narcotics trade in hashish, opium, heroin and morphine, according to U.S., United Nations and other estimates. Much of the money went to pay for weapons, explosives, soldiers for hire and bribes to corrupt government officials.

For decades, much of the region’s narcotics trade had been controlled by the Quetta Alliance, a loose confederation of three powerful tribal clans living in the Pakistani border town of the same name. At a June 1998 summit, the clan leaders gathered secretly to approve another alliance — with the Taliban, which ruled Afghanistan at the time, according to classified U.S. intelligence cited in Operation Reciprocity legal documents.

Under the “Sincere Agreement,” the drug lords pledged their financial support for the Taliban in exchange for protection of their vast swaths of poppy and cannabis fields, drug processing labs and storage facilities. The ties were solidified further when the U.S. invasion toppled the Taliban after 9/11 and forced top commanders to flee to Quetta, where they formed a shura, or leadership council.

In the early years of the U.S. occupation, the Pentagon and CIA cultivated influential Afghan tribal leaders who were not part of the Quetta Alliance, even if they were deeply involved in drug trafficking, in order to turn them against the Taliban. That willingness to overlook drug trafficking was assisted by their belief that the drugs were going almost entirely to Asia and Europe.

But a lot of Afghan heroin was also coming into the United States, indirectly, including through Canada and Mexico, according to DEA, Justice Department and congressional officials and documents. Over time, growing numbers of Americans addicted to legally prescribed opioids were finding an alternative in the ample, but often deadly, narcotics supply on the streets.

Even as the body counts mounted in Afghanistan, few Americans associated the war with growing opioid death and addiction rates in the U.S., including, importantly, appropriators in Congress. Lawmakers spent billions of taxpayer dollars annually on both the U.S. military campaign and reconstruction effort. But they earmarked just a tiny percentage of that for DEA efforts to counter the drug networks bankrolling the increasingly destructive attacks on both of them, records and interviews show.

As a result, as of 2003, the DEA deployed no more than 10 agents, two intelligence analysts and one support staff member in the entire country.

The agency’s primary mission was to disrupt and dismantle the most significant drug trafficking organizations posing a threat to the United States. Another mission was to train Afghan authorities in the nuts and bolts of counternarcotics work so that they could take on the drug networks themselves.

Over the next three years, as the U.S. military cut back its presence in Afghanistan to focus on the Iraq War, the Taliban roared back to life. The DEA agents and their Afghan protégés were left to stanch the flow of drug money to the growing insurgency.

Even after the U.S. and NATO countries began adding troops in 2006, the Afghan police and military counternarcotics forces were outgunned, outnumbered and outspent by the drug traffickers and their Taliban protectors, according to documents and interviews.

Kabul’s criminal justice system remained a work in progress. Afghan prosecutors, with help from the DEA and the Justice Department, were putting away 90 percent of those charged with narcotics crimes. But most were two-bit drug runners whose convictions didn’t disrupt the flow of drug money, records show.

Washington was coming to the realization that the Kabul government lacked the institutional capacity and the political will to take on the top drug lords, according to Rand Beers, who held a top anti-narcotics position in the George W. Bush administration.

Lucrative bribes had compromised police and government officials from the precinct level to the inner circle of U.S.-backed President Hamid Karzai. That meant the more senior that suspected drug traffickers were, the less successful U.S. authorities were in pressuring the Afghans to act against them.

As had been the case in Colombia, the drug kingpins were overseeing what had become vertically integrated international criminal conglomerates that generated billions of dollars in illicit annual proceeds. That made them, effectively, too big for their home government to confront.

The only criminal justice system willing and able to handle such networks was the one in the United States. By then, the U.S. Justice Department had indicted and prosecuted significant kingpins from Mexico, Thailand and, beginning in 2002, dozens of FARC commanders and drug lords from Colombia.

In response, the DEA took two pages from its “Plan Colombia” playbook. It began embedding specially trained and equipped drug agents in military units, to start developing cases against the heads of the trafficking networks. It also worked closely with specially vetted Afghan counternarcotics agents. These Afghans were chosen by DEA agents for their courage, experience and incorruptibility, and then polygraphed and monitored to keep them honest.

Together, the vetted Afghans and their DEA mentors established a countrywide network of informants and undercover operatives that penetrated deeply into the transnational syndicates. The crown jewel of that effort was a closely guarded electronic intercept program, in which DEA agents showed their Afghan counterparts how to obtain court-approved warrants and develop the technical skills needed to eavesdrop on communications.

The hundreds of warrants authorized by Afghan judges provided a real-time window into the flows of drugs and money — from negotiations of individual narcotic sales to forensic road maps of the trafficking networks’ logistics and financial infrastructure. DEA agents also worked with a special Sensitive Investigative Unit to map the drug, terror and corruption networks.

As the insurgency grew and became more costly to sustain, that evidence began to show the Taliban methodically assuming a more direct operational role in the drug trade, pushing out middlemen and extracting more profit — and money for the war effort — at every step of the process. All of the evidence was admissible in courts in Kabul and the United States. And it led agents straight to the top of the Taliban leadership — including its one-eyed supreme commander, Mullah Mohammad Omar, according to documents and interviews.

By the end of the Bush administration, the Justice Department had indicted four top Afghan drug lords, who were ultimately captured and flown stateside or lured there under pretense, then prosecuted and convicted. A top-secret “target list” circulating at the time drew a bull’s-eye on three dozen others who were next in the barrel, a Pentagon counternarcotics official said in an interview.

As Bush prepared to pass the reins of government to Obama, it was clear to both administrations that the Afghan government wouldn’t be able to halt the flow of drug money to the insurpgency on its own.

Bush’s outgoing Ambassador William Wood acknowledged as much in a withering cable back to Washington in January 2009, saying that the narcotics trade had become so pervasive that it made up one-third of Afghanistan’s gross domestic product, but “no major drug traffickers have been arrested and convicted [by local authorities] in Afghanistan since 2006.”

The battle against the Taliban would have to extend to courtrooms in the United States.

Launching ‘Plan Afghanistan’

The incoming Obama administration also publicly backed the “kingpin” strategy, as part of a counterinsurgency plan that focused on increased interdiction and rural development.

“Going after the big guys” was how Richard Holbrooke, Obama’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, described it to Congress.

That March, the DEA announced the most ambitious overseas deployment surge in its 40-year history — a six-fold increase of agents from 13 to 81.

Not everyone was an unflinching fan of the DEA’s approach. Many people in and out of the government feared that targeting those at the apex of the drug trade could backfire in a place like Afghanistan, where it often meant taking on tribal leaders with armies of fighters, tanks and even missiles at their disposal, recalled Kenneth Katzman, a senior analyst on Afghanistan issues for the Congressional Research Service, the independent research arm of Congress.

“These guys are powerful people,” Katzman told POLITICO. “Many have militias, and there are tribes, and subtribes, that depend on them for sustenance. You try to arrest someone like [that] and you are going to have a rebellion on your hands.”

But Haidari — then Afghanistan’s top national security diplomat in Washington — hailed the shift as being not only urgently needed but long overdue.

“A surge not only of military but law enforcement is exactly what we need,” said Haidari, who was then a senior official in the Karzai government. “It is something we have always demanded of the U.S. government.”

The DEA agents answering the call included a former Denver Broncos linebacker-turned-wiretapping expert and a former Marine with a Harvard Law degree. Several veteran commandos of the agency’s Latin American drug wars signed up too, including one storied agent who had built the case against the FARC.

“It was ‘Game on,’” Marsac said. “People wanted in on the fight. We were pulling them in from everywhere, and bringing them over in waves.”

After completing several months of special operations training, new agents hit the ground running, sweeping through fortified drug compounds as allied military forces provided cover fire. The agents seized and cataloged as evidence multi-ton caches of narcotics, as well as stockpiles of Taliban weapons found, increasingly, alongside them.

In November 2009, three DEA agents and seven American soldiers were killed when their helicopter crashed after a particularly intense drug raid in western Afghanistan. Obama and his attorney general, Eric Holder, traveled to Dover Air Force Base to receive their bodies.

For the tight-knit and fast-growing DEA team in country, the fight against the Taliban was, from that point on, an intensely personal one. So-called FAST teams — for foreign-deployed advisory support — brought Afghan drug agents to the front lines of the drug war, including Helmand Province, the epicenter of both the drug trade and the insurgency. U.S. and coalition military forces now embraced both the DEA agents and their Afghan trainees as full partners who were making significant inroads in attacking the increasingly intertwined drug-terror networks.

On June 22, 2011, Obama formally announced a September 2014 drawdown date for almost all U.S. troops and DEA agents. Marsac, the leader of all the DEA staff in the region, figured he had two years, at most, in which to marshal his agency’s newfound horsepower in ways that would make a lasting difference and give the Afghans a fighting chance on their own.

There wasn’t time to wrap up the myriad open investigations, even the multiyear ones targeting the kingpins. So Marsac proposed a legal Hail Mary of sorts: one giant U.S. conspiracy prosecution of the trafficking chieftains and the Taliban associates they financed.

In January 2012, he assembled a team to review the mountains of evidence in DEA vaults to see whether it supported such a prosecution.

The Justice Department had used such “wheel conspiracy” prosecutions for decades against international organized crime syndicates and drug cartels that had many tentacles. One especially potent advantage of such an approach was that evidence gathered against each defendant could be used to strengthen the overall conspiracy case against all of them.

The team concluded that the evidence didn’t support a conspiracy case centering on the fractious and fragmented trafficking networks. But Marsac believed it might support something even more audacious, which DEA and Justice had never done before: a conspiracy case combining major drug traffickers and terrorist leaders.

The Taliban senior leadership would be the hub in the center of the wheel, and its various trafficking partners, money launderers and the Quetta Shura the spokes arrayed around it. The main charge: That the Taliban had engaged in a complex conspiracy to advance the war effort through the production, processing and trafficking of drugs.

Marsac obtained approval from DEA’s Special Operations Division, a multi-agency nerve center that coordinates complex international law enforcement efforts. His deputy later did the same with DEA’s New York field office, which would be needed to help with support and logistics, such as safeguarding evidence and shepherding Afghan witnesses in country to testify before the grand jury hearing testimony in the case.

Marsac opened an official case file and, requiring a name, called it Operation Reciprocity. It would be DEA’s way of settling the score against the Taliban, he told the team, for its complicity in the 9/11 attacks and the deaths of the DEA’s own agents.

A tapestry of criminality

By the end of 2012, the team members were struggling to make progress on building the conspiracy case, given their crush of daily caseload demands. So Marsac asked the Justice Department attache in Kabul for reinforcements.

Specifically, Marsac wanted John Seaman, his old partner from their early days in Denver, who had become one of the DEA’s top experts in building conspiracy cases. After retiring in 2005 and doing some contract police work in Iraq, Seaman had spent the previous year on a Justice Department contract helping the Afghans identify sensitive anti-corruption and drug cases to pursue.

With time running out in Afghanistan, Marsac hoped Seaman could find a way to jump-start Operation Reciprocity. The Justice Department’s attache in Kabul, David Schwendiman, himself a veteran prosecutor of international war crimes tribunals, quickly approved the request.

Marsac and Seaman believed the evidence for a Taliban-led conspiracy existed somewhere in the thousands of intercept recordings, cooperating witness statements, financial transaction records and everything else that DEA personnel had gathered, processed and filed away since first deploying in 2002. Seaman’s particular talent was in finding the puzzle pieces and understanding how they fit together.

Seaman, who was then 60 years old and a cancer survivor, scoured the evidence with focused intensity. Marsac would often leave work around 10 p.m., he said, “and I’d come back in the morning and John would still be still there.”

Marsac and Seaman believed the evidence for a Taliban-led conspiracy existed somewhere in the thousands of intercept recordings, cooperating witness statements, financial transaction records and everything else that DEA personnel had gathered, processed and filed away since first deploying in 2002. Seaman’s particular talent was in finding the puzzle pieces and understanding how they fit together.

Seaman, who was then 60 years old and a cancer survivor, scoured the evidence with focused intensity. Marsac would often leave work around 10 p.m., he said, “and I’d come back in the morning and John would still be still there.”

Schwendiman, the Justice attache, was encouraged. He sent for the FARC case files from Washington and determined that the Kabul investigators exceeded the standard of evidence used to indict and convict the Colombian guerrilla commanders in U.S. courts.

On his recommendation, the team sent the prosecution memo to the Justice Department’s Terrorism and International Narcotics unit in the Southern District of New York, which was known for taking on, and winning, the most ambitious and complex conspiracy cases.

Three Operation Reciprocity agents flew to Manhattan to brief the prosecutors, who quickly greenlighted taking the case. They spent three hours strategizing and discussing the monumental challenges inherent in building such a case, securing final DOJ headquarters approval and taking it to trial. The logistical hurdles would be predictable — and surmountable — but the political ones would not.

All agreed, however, that with Afghanistan descending into chaos, they had to try, according to Michael Schaefer, the supervisory DEA agent leading the investigation, and a second meeting participant.

Bringing Mullah Omar and at least some of his top commanders to New York was unlikely, given the military’s inability to kill them over the past decade, they figured. But handing up detail-rich indictments would have immediate, as well as long-term, benefits, they said.

Exposing the Taliban leadership’s direct role in the narcotics trade would undermine its campaign to win political legitimacy internationally. Related sanctions would block its access to the global financial system. And international arrest warrants, Schaefer said, would “fence in” the younger indictment targets enjoying jet-setter lifestyles outside Afghanistan.

The indictments also would empower authorities everywhere to attack the drug lords’ transport and distribution networks, which snaked through dozens of countries, including the United States. And, the agents and prosecutors concluded, the case would serve as a model for prosecuting other narco-terrorist organizations, especially those operating in places where military force isn’t an option, Schaefer recalls.

Fee, the newly appointed prosecutor, had won convictions against FARC commanders, Al Qaeda terrorists who blew up two U.S. embassies in Africa and other international defendants. He knew how to manage the intractable conflicts arising in such cases with U.S. diplomatic, intelligence and military officials. So the DEA agents were especially buoyed by Fee’s assessment that the case was winnable.

“He told us the evidence was so strong,” Schaefer said, “that I’m ready to put you guys in front of a grand jury right now.”

Back in Kabul, DEA chief Marsac shared the news with McFarland, the State Department’s law enforcement coordinator. The 35-year veteran diplomat had been a forceful advocate for the DEA in Afghanistan, especially when Kaidanow opposed enforcement efforts she believed would upset influential Afghan constituencies, McFarland told POLITICO. Given that history, he said, he concluded that he had to tell her the news immediately, and that she wasn’t going to like it.

“I knew I would be walking into the middle of a shit storm,” he said. “I just had no idea how big it would be.”

Throwing a wrench into things

Kaidanow was, indeed, enraged during the meeting in her office, and accused the three men she had summoned there of insubordination, they said. What’s more, she told them, they had undermined the Obama agenda in Afghanistan by proposing the plan and getting Justice Department buy-in without her knowledge or approval, Marsac and McFarland said. “She said you’re throwing a wrench into things,” Marsac said, “but in a lot stronger language than that.”

Schwendiman declined comment for this article but gave a similar account in two confidential internal Justice Department memoranda obtained by POLITICO.

Kaidanow also threatened to “curtail” the three officials, the State Department term for firing them from their embassy positions and sending them home, the men said. But first, she gave Marsac three minutes to explain why she shouldn’t shut down the operation immediately. He ticked off the reasons, including that any indictments were months away. They could be kept secret, or leveraged strategically to help, not hinder, U.S. negotiators during peace talks.

The way Marsac saw it, the case would show that the U.S. was committed to the rule of law, by prosecuting narco-terrorists as criminals rather than killing them with military force. Also, U.S. intelligence showed that Taliban drug lords were so against peace talks that they were threatening, and killing, associates who even considered them. With the drawdown imminent, he believed, Taliban shot-callers were just feigning interest in negotiations to burnish their political credentials and run out the clock.

Before Marsac could finish, he said, Kaidanow cut him off, ordering him to stand down the operation and retrieve all documentation about it from the Justice Department.

The DEA and Justice officials didn’t know it at the time, but they were proposing to indict top Taliban leaders at the exact moment the administration was secretly finalizing the launch of peace talks with the organization, set for Qatar the next month.

Secretary of State John Kerry was arriving even sooner to soothe President Karzai, who was furious that the White House had excluded his government from the talks, POLITICO has learned. And clandestine negotiations were well underway already with the Taliban to get back Bergdahl, the Army sergeant who had deserted his post four years earlier, several current and former U.S. officials confirmed.

The way Kaidanow saw it, the problem wasn’t just one of spectacularly bad timing. Pitching the plan to Justice was part of a pattern in which the DEA team — and its supporters at the embassy — had defied her “chief of mission authority,” or her role as coordinator of all U.S. agencies in the country in order to accomplish the administration agenda.

“We were trying very hard to keep Afghanistan on a course, and there was no single way to address the Taliban problem,” Kaidanow said, adding that her interest in putting the brakes on any DEA efforts in country would have been driven by concerns that “everything they did was well vetted and coordinated” with other U.S. efforts.

Kaidanow declined to comment on the three men’s accounts of the meeting, but denied threatening to dismiss anyone. But, she said, “In my career I have had to make many tough decisions that have not pleased everyone, but, as deputy chief of mission, I was responsible for implementing the policy set by the administration, and I stand by those decisions.”

In interviews, the DEA and Justice officials countered that while Kaidanow did coordinate the overall U.S. mission in Afghanistan, they also were deployed there to represent the best interests of their home agencies internationally.

As such, they reported, ultimately, to top DEA and Justice officials in Washington, who would decide whether to approve any Taliban indictments in consultation with others in the interagency process. Often, they said, they weren’t allowed to discuss such investigations with embassy leadership due to concerns about well-connected targets being tipped off.

After the meeting with Kaidanow, Marsac went straight to his office and drafted a formal appeal. Instead of sending it, though, he and Schwendiman opted to lay low and launch their appeal after Kaidanow returned to Washington in the fall. Schwendiman enlisted McFarland in the plan, saying in a July 3 letter that they should lay the groundwork “as soon as we can.”

“But there is no reason to think coming back to it in six months when cooler heads prevail will damage [its] prospects,” Schwendiman wrote.

Waiting, however, turned out to be a fatal mistake.

Nine days after Schwendiman’s letter, McFarland was sent back to Washington. In an effort to keep his job, McFarland had formally apologized to Kaidanow, assured her that the case files had been retrieved from Justice, and said he had much to contribute during what would certainly be a difficult handover of law enforcement affairs.

“I said a procedural mistake was made here, we corrected it and no harm was done,” McFarland told POLITICO.

Kaidanow denied forcing him out, but he maintained that she played a role in doing so. McFarland said her response was “totally disproportionate” and served to torpedo his chances of securing another ambassadorship. He left the State Department not long after returning to Washington.

But McFarland has no regrets about supporting the Taliban indictment plan, which he said was totally in line with what the DEA was supposed to be doing in Afghanistan.

“If you’re out there killing Americans,” he said, “it’s fair for us to go after you, not just with guns but to go after your [drug] money too.”

Leaving the Afghans blind

The Operation Reciprocity team unraveled quickly after that.

Marsac himself left in August, citing a long-overdue transfer to DEA headquarters to be closer to his wife and daughter. He too took early retirement soon after that.

Also in August, Schwendiman wrote a secret memorandum warning a senior Justice official in Washington that Kaidanow had iced Operation Reciprocity and ousted McFarland as part of a broader campaign to immediately shut down all U.S. law enforcement operations in Afghanistan — especially the DEA’s — even though the drawdown was more than a year away.

Without McFarland to protect those operations, Kaidanow was going so far as to block DEA agents from investigating cases with their Afghan counterparts, the Justice attache wrote in the Aug. 22, 2013, “For Your Eyes Only” memo. And she was eliminating so many DEA positions in country, Schwendiman wrote, that it would be “problematic if not impossible” for Afghanistan to maintain the intelligence-gathering programs that formed the backbone of its entire counternarcotics and anti-corruption effort.

That would undermine U.S. security interests in Afghanistan, wrote Schwendiman. “The Afghans, of course, will be left blind if this happens,” he added.

In December, Schwendiman retired from the Justice Department and soon took a top job in Kabul for SIGAR, the independent U.S. watchdog agency known formally as the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. Seaman also cut short his Justice Department contract, and returned stateside.

Schaefer had some success in obtaining embassy buy-in after Kaidanow left. But by early 2014, some influential new DEA management officials were not supportive, saying the evidence for such a wide-ranging conspiracy wasn’t there, that they lacked the bandwidth to develop it or that they favored some individual prosecutions also underway in New York, according to Schaefer and other current and former DEA and Justice Department officials. In interviews, some said their agencies were reluctant to lock horns with the White House as the drawdown loomed. Others cited internal DEA turf battles, and changing agency priorities, including a major refocus on domestic cases.

“We just never got our legs back under us to make a go of it again,” said Schaefer, who soon retired too, and joined Schwendiman at SIGAR.

Ultimately, the Taliban peace talks went nowhere. Bergdahl was freed a year and four days after Kaidanow’s stand-down order. But in return, Taliban leaders got back the same five senior commanders held at Guantanamo Bay they had demanded at the outset of the talks.

“Since the White House ultimately gave the Taliban everything they wanted,” one DEA official asked, “what’s their excuse for not letting us build a case against them all that time?”

By the end of 2014, the DEA was down to fewer than a dozen personnel in Afghanistan, rendering obsolete much of a decade’s worth of investigative casework. And as Schwendiman warned, the slashing of DEA support crippled the Kabul government’s ability to counter the narcotics cartels on its own, the DEA officials said.

The impact was immediate. In 2015, State Department statistics show, the Taliban — cash rich from record drug profits — surpassed the Islamic State as the deadliest terrorist group worldwide, both in the number of attacks and fatalities. The year before, ISIS was, by far, the leader.

Frustrated by the deteriorating situation, Seaman self-published a 104-page manuscript in 2016 detailing 14 years of unfinished DEA counternarcotics investigations in Afghanistan, accusing the Obama administration of placing short-term political points over long-term security interests. He did not go into the circumstances surrounding the shutdown of Operation Reciprocity but was particularly critical of the Obama team’s decision “to seek peace talks with the Taliban in lieu of pursuing them in U.S. courts, when in fact both could have been accomplished simultaneously.”

Past administrations, in contrast, had the political will to indict the FARC leadership, he wrote, “exposing their criminality to the world while the Colombian government was involved in peace talks with the FARC” that, years later, ultimately proved successful.

None of the DEA and Justice Department officials said their decision to leave Afghanistan, or to retire, was influenced by the abrupt shutdown of Operation Reciprocity. But every one of them told POLITICO that they believe their colleagues called it quits because of their inability to work on the conspiracy case they had spent years building.

“We had a lot of successes in spite of the obstacles,” Schaefer said, “but our biggest shot at success was stolen from us.”

From operations to advice

Over the past five years, the existence of Operation Reciprocity — and its demise — have remained known only to a relative handful of agents and diplomats.

Several current and former U.S. officials said that while they were not familiar with it, the case is emblematic of a far more fundamental conflict at play in Afghanistan — and Iraq — as Washington struggles to contain the hybrid threats that emerged in the post-9/11 world.

On one side are U.S. law enforcement officials tasked with investigating drug trafficking, organized crime and corruption at the highest levels in those countries. On the other: Diplomats responsible for seeking accommodation with many of those under suspicion, in order to maintain stability, and a working government.

In Afghanistan, many U.S. officials — and numerous coalition allies — supported the DEA’s targeting of Taliban leadership on drug trafficking charges “as a much more strategic and fruitful way forward” than either military force or negotiations, said Candace Rondeaux, a strategic U.S. adviser for SIGAR at the time.

But some U.S. diplomats — like Kaidanow — believed spotlighting Taliban leaders’ drug trafficking activities would create too many barriers to an eventual armistice, Rondeaux said. Meanwhile, some Pentagon and CIA officials still protected certain drug lords, citing their purported value as intelligence assets and strategic allies.

Such conflicts are to be expected, Rondeaux said. But the Obama administration compounded the problem significantly by not stepping in and protecting its $8 billion-plus counternarcotics investment, despite its 2009 vow to go after “the big guys” atop the drug trade.

“This was a problem, fundamentally, of leadership in the White House and a lack of structure within [it] to direct dollars and identify priorities,” said Rondeaux, who is now a senior fellow at the nonpartisan think tank New America’s Center on the Future of War.

One senior Obama-era Pentagon counternarcotics official told POLITICO that high-level administration officials, at the National Security Council and elsewhere, did, in fact, undermine the plan to indict Taliban leaders. “The NSC was aware of it, [and] it ran headlong into the issue of engagement” with the Taliban, he said.

Operation Reciprocity, like some Hezbollah cases before it, died from a lack of political support, the official said, rather than an organized conspiracy to shut it down. Even so, the result was the same. “You can kill things by not moving it,” he said. “If DEA is waiting for approval and someone says no, you have to pause, that’s pretty much it.”

In interviews, Obama administration officials, including Kaidanow, denied that political tradeoffs undermined Operation Reciprocity or the broader DEA effort in Afghanistan. The White House always favored an “all-tools approach, using law enforcement, diplomacy, sanctions, military, capacity building” in Afghanistan, one senior White House official said.

“You can argue that one could have been used more,” the former official said, about the plan for indictments. “But I never got the impression that that [all-tools] approach deviated due to the Taliban discussions” about peace talks.

Kaidanow said all decisions on how, and when, to downsize DEA operations in Afghanistan were based on the administration’s overall withdrawal plan, which included transitioning DEA to an advisory role. She also said DEA agents wouldn’t be able to operate throughout the country once military protection and transport were gone.

Since the 2014 drawdown, the dozen or so DEA personnel in Afghanistan have, indeed, remained almost entirely “inside the wire,” or within the fortified U.S. Embassy compound, one drug agency official said.

“We’re not doing operations there,” just advising Kabul authorities, the official said.

Two senior DEA officials acknowledged that shutting down Operation Reciprocity and withdrawing most agents significantly undermined the overall counternarcotics effort in Afghanistan, but said DEA never stopped focusing intensively on top Taliban drug kingpins and their global operations.

“I don’t like the fact that the State Department did that, but I knew that we would continue to move forward” by working with government counterparts and its own informants in Afghanistan and other affected countries, one of the senior DEA officials said. “That was all happening as we were in an advisory role,” and led to significant arrests and convictions, including two Afghan traffickers in Thailand in 2015 and a Pakistani drug kingpin in Liberia in 2016.

Recently, top Trump administration officials have made several trips to Afghanistan to discuss more troop deployments and peace talks. They included Lisa Curtis, the deputy assistant to the president and senior director for South and Central Asia on the National Security Council.

Back in 2013, several months after Operation Reciprocity was halted, Curtis — a former senior Afghanistan hand at the State Department and CIA — wrote a Heritage Foundation policy paper imploring the Obama administration to commit to a long-term counternarcotics effort in Afghanistan as it handed over security operations.

“Although the fate of Afghanistan rests with its own people,” she wrote, “without leadership and assistance from the U.S., it will devolve into a narco-terrorist state that poses a threat to regional stability and to the security of the broader international community.”

But Curtis, who declined interview requests, and other Trump officials have said little publicly, if anything, about whether the DEA and Justice Department figure into their plans to stop the Taliban and drug lords from seizing control of Afghanistan.

“The U.S. strategy is taking into account the counternarcotics challenge, and the U.S. is considering how to address the issue,” an NSC spokesperson said in response to questions from POLITICO. “Our strategy of confronting the Taliban militarily not only will bring them to the negotiating table but will set the conditions necessary for further counternarcotics effort.”

Haidari, the senior Afghan official who helped lead those talks, said his government is wary of a third consecutive U.S. administration promising a military-only solution to its problems.

“We felt betrayed,” he said, by Obama officials “who saw no reason to expand counternarcotics, and to go after these kingpins and their accomplices.”

The DEA and Justice Department, he said, “should have continued to build upon what they had achieved based on the surge,” especially training programs designed to help Afghans take on the drug networks on their own.

Marsac, the former DEA chief, said it would take years to rebuild that capacity in Afghanistan. But a small team of U.S. and Afghan drug agents could make an immediate dent in the insurgency, he said, by using the Operation Reciprocity case files to attack a Taliban-drug nexus that has changed surprisingly little since the project was, essentially, flash-frozen back in 2013.

“They asked us to do a job, and we went out and did it,” Marsac said. “It needs to be completed.”

This piece originally appeared on www.politico.com on July 08, 2018. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.