Two new reports have found that despite improvements in some sectors, aid delivery in Afghanistan is still largely ineffective and poverty has risen. A joint Oxfam and Swedish Committee for Afghanistan (SCA) report on aid effectiveness reveals that while development aid has decreased, donor support continues to be fragmented and aid dependency remains high. Meanwhile, Afghanistan’s new Living Conditions Survey shows that poverty is more widespread today than it was immediately after the fall of the Taleban regime. AAN’s Jelena Bjelica and Thomas Ruttig summarise, contextualise and analyse the reports’ findings.

A new joint report by Oxfam and the Swedish Committee for Afghanistan (SCA) entitled “Aid Effectiveness in Afghanistan” (1) assessed efforts by both donors and the Afghan government to align with criteria provided by the 2005 Paris Declaration on aid effectiveness and builds on a 2008 Oxfam report on aid effectiveness. (2) The report – which was informed by a comprehensive review of the ministries’ and other government institutions’ primary data as well as interviews with key-informants among government, donors, development partners and civil society – comes to the conclusion that the continuing “fragmentation” of aid provided in many sectors still “leads to ineffective aid.” The report states that:

There are over 30 different international donors disbursing aid in Afghanistan, each with their own agenda and aid agreement with the government, and effective donor coordination and harmonisation is not a practice adopted universally […] Yet there are still major issues of fragmentation, with donors bypassing government systems in multiple areas of the development sector, and it is this fragmentation that leads to ineffective aid.

The 2008 Oxfam study had already uncovered worrying facts and figures about how ineffectively aid in Afghanistan had been disbursed and spent in the period from 2001 to 2008. The report revealed that over two-thirds of the aid – then around 20 billion USD in total – bypassed the Afghan government. Donors justified this practice by pointing to the endemically corrupt Afghan system, arguing that channelling money through government and non-governmental organisations guaranteed better financial accountability. This argument was bolstered by the findings in the report that the Afghan government did not know how the remaining third of the aid, which was around five billion USD, had been spent, due to a lack of internal communication and coordination.

The 2008 report also found that “over half of aid is tied, requiring the procurement of donor-country goods and services.” Furthermore, it pointed out that large sums of development money was siphoned off, particularly through reconstruction contracts “for international and Afghan contractor companies,” where profit margins were “often 20 per cent and can be as high as 50 per cent.” It also criticised the exaggerated salaries of “most full time, expatriate consultants, working in private consulting companies, [who] cost 250,000–500,000 USD a year.” It estimated that 40 per cent of aid since 2001 – around six billion USD – had returned to donor countries in corporate profits and consultant salaries, effectively turning aid into donor countries’ export promotion. A World Bank report published in the same year stated that spending “on” Afghanistan did not equal spending “in” Afghanistan, and that “only 38 cents of every aid dollar spent in Afghanistan actually reaches the economy through direct salary payments, household transfers, or purchase of local goods and services.” (More in this AAN analysis)

What does the new Oxfam/SCA report say in detail?

Around 66 per cent of Afghanistan’s budget in the financial year of 1396 (March 2017-February 2018) was funded through international donor support, according to the Oxfam/SCA report. Only 33 per cent came from domestic revenues, even though revenue has tripled over the last ten years, from around USD 750 million in 2008/09 to USD 2.5 billion in 2017/18. These figures reflect a continuing high level of aid dependency. (3) Additionally, the report said (with reference to a 2016 Afghan government update through the Self-Reliance Through Mutual Accountability Framework (SMAF) that 59 per cent of development aid provided by the international community had gone through the government’s core budget that year. But this percentage fluctuates on a yearly basis: in 2015, for example, of 3.73 billion USD disbursed, around 40 per cent was provided through the budget (see here).

The funds Afghanistan receives are mainly channelled through donor-run projects as well as trust funds, which are usually designed as multi-year endeavours and managed by donors. For example, for a major aid investment such as the Afghan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF), although it is a fully ‘on-budget’ programme, programmatic decisions are still made by the World Bank. This is strongly influenced by donors’ investment choices and restricts governmentownership of the ARTF, as the Swedish government’s development agency SIDA reported in a 2015 evaluation (http://www.sida.se/contentassets/72dc94b2318644e9b70242b037660cfd/7a6d0a72-27e6-4bad-b17d-a44c1028ae45.pdf). This approach to budgeting, however, has resulted in the ‘over-aiding’ of the country by allocating more funds than needed for the multi-year cycles. This was also highlighted by the 2016 Afghan Ministry of Finance annual performance assessment report.

The fragmentation of aid is reflected by the fact that funds for the 6.659 billion USD Afghan government budget for 2017/8 were provided by over 30 different international donors. (4) The Oxfam/SCA report stated that each donor maintains its own agenda based on separate aid agreements with the government and highlighted that donors mainly choose to fund areas that appeal to their constituents back home:

With the government largely only able to influence where the money goes, donors are free to fund areas that are appealing to their constituents back home. Therefore, when it comes to the National Priority Programs, where the government has a clear plan for what they would like funded, donors have been known to compete for the most attractive projects, with other development areas neglected if they do not appeal.

In conclusion to its extensive analysis about whether the Afghan government and the international community have met their aid effectiveness commitments pledged in the past four international conferences on Afghanistan (Kabul 2010, Tokyo 2012, London 2014, Brussels 2016), the report reiterated the same finding: development support continues to be fragmented. However, it commended the efforts made by the Afghan government and the donor community to better align and coordinate aid, with the development of national priority programmes (NPPs) and the strengthening of the Joint Coordination Monitoring Board (JCMB), and noticed that in some sectors, however, donors do coordinate well. Mechanisms such as the Afghan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) and the Afghan Infrastructure Trust Fund (AITF) are given as examples of this “harmonised approach.” SIGAR’s new report on the ARTF, however, disagreed with this Oxfam/SCA finding. According to SIGAR, the World Bank, which manages the fund, “restricts donor and public access to how it monitors and accounts for ARTF funding, leaving donors, and their taxpayers, without important information necessary to understand the activities they fund.” The SIGAR report also states, “the Bank is not following its own policy to provide donors and the public access to ARTF records that should be publicly available.”The World Bank press release in response to the SIGAR report called “most of the findings […] somewhat anecdotal.” Nevertheless, both the SIGAR and Oxfam/SCA report, while they contradict each other on this particular topic, point to poor management, coordination and monitoring of development aid money in Afghanistan. While the Oxfam/SCA report notes this is the case in general for all development aid provided, the SIGAR report states the same for a specific trust fund. Both reports also note that the lack of transparency further exacerbates the unaccountability of development aid funding in the country.

According to the Oxfam/SCA report, the area that has received most financial support is social infrastructure and services, with over 14 billion USD from 2011 to 2015. This is followed by economic infrastructure and services (4 billion USD), humanitarian aid (2 billion USD), and production sector support (1.6 billion USD). It further offers a detailed overview and effectiveness assessment of the projects funded in each of the above-mentioned sectors.

It also found that in 2014 the majority (58.7 per cent) of donor financed ‘off-budget’ projects were below one million USD, and nearly a third between one and ten million USD. “By contrast,” the report stated, “more than a quarter of ‘on-budget’ projects in 2014 were in the 10-50 million USD category and only 21.7 per cent of on-budget projects were less than 1 million USD.” This, according to the report, means that donor support is more fragmented when provided off-budget:

The implementation of a large number of small projects, involving a large number of implementing agencies, despite existing coordination mechanisms, can lead to increased transaction costs for both donor agencies and the Government. Donors may decide to deliver aid this way to reduce their reputational risk, however it can actually increase their fiduciary risk with more resources needed to keep an eye on multiple projects, and eventually increase the long-term development risk as government ownership of this type of development approach remains limited.

It is also evident from the now publicly available and searchable Afghan annual budgets, that the government annual budgets are structured around projects (see here)and not, for example, on sub-national units like provinces or districts.

Additionally, the report states, “a decreased appetite for risk, due to the deteriorating security situation,” the report said, “impacts on their ability to coordinate […] on their ability to share information and agree to common efforts for development advocacy and planning.” This inevitably impacts national development priorities as set out by the government, and often means donors are unable to fund projects in large parts of the country. A development worker who wished to remain unnamed, told AAN that around 40 per cent of the country was not privy to donor funds. This further widens the gap between rich and poor, increasing inequality in society, as mentioned above. A lack of donor coordination and an uneven distribution of donor funds, as well as favouritism of certain projects have contributed to an increase in anti-government sentiments in some parts of the country.

The report does not adequately address the question of the extent to which aid spent by the Afghan government and the international community has been effective (or spent on intended purposes). In the report’s analysis of projects, it is unclear whether they were funded by the government or directly by donors.

What budgeting has to do with aid effectiveness

According to financial experts, the aid channelled through donor-run projects and trust funds almost never uses policy-based budgeting techniques (see here; see also the explanation about ARTF, above), ie the funding associated with these projects lacks the precise identification of public policy objectives, delineation of the means and resources for accomplishing them and an accurate assessment of accomplishments. The funds channelled through projects are linked to “results targets” and “log frames,” the set of qualitative and quantitative measurements that are set in project management paradigms and not budgeting and fiscal accountability paradigms, which should be the case when it comes to state-level budgeting. This, in practice, translates into what the 2008 Oxfam report described as:

[…] A large proportion of aid has been prescriptive and supply-driven, rather than indigenous and responding to Afghan needs. [… Aid] has tended to reflect expectations in donor countries, and what western electorates would consider reconstruction and development achievements, rather than what Afghan communities want and need. Projects have too often sought to impose a preconceived idea of progress, rather than nurture, support and expand capabilities, according to Afghan preferences.

The 2008 Oxfam report highlighted that,according to the 2006 Paris Declaration Survey, only 52 per cent of development aid allocated to Afghanistan during the early years of the intervention had been disbursed “in agreement with the government.” This estimate included all funds provided – both to the core budget and for projects where there was a signed agreement or memorandum of understanding with a ministry or government agency. In the period from 2012 to 2014, according to the Afghan government donor coordination report quoted in the 2018 Oxfam/SCA report, only 4.4 billion USD of development assistance were considered to be aligned with national priority programmes; the remaining 8.4 billion USD were considered counter to estimated needs and priorities. (See also the 2016 Ministry of Finance annual performance assessment).

Over the years, this approach also increased incentives to so-called auction-based budgeting (see here). This, in practice, means that annual budgets in Afghanistan are designed in an auction-like process. This happened most recently in 2017 when the Afghan annual budget was only passed by parliament after the Ministry of Finance agreed to allow each MP to have ‘their’ projects included in the budget (see AAN analysis here). (5) The process of auction-based budgeting, nevertheless, is where the largest incidents of misallocation, mismanagement, and outright corruption usually take place, experts say. The amount of rents, experts estimate, that can be lost through the auction process can be as high as 20 to 40 percent of a budget.

Many reports on Afghanistan reflect exactly this: that a considerable amount of donor funding to Afghanistan has been misappropriated through corruption or misallocation, despite both donor and government efforts to create accountability and transparency mechanisms (see here). A 2016 report entitled “Corruption in conflict: Lessons for the U.S. experience in Afghanistan” from the US government’s Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), for example, strongly criticised its own government for pouring billions of dollars into Afghanistan with so little oversight that it fuelled a culture of “rampant corruption” and undermined the US mission (see also here and here). (6)

Dropping aid levels

The Oxfam/SCA report also provides an overview and analysis of development and humanitarian aid to Afghanistan during the period 2010 to 2015 that equalled 34.3 billion USD. This is part of a total of development aid assistance, between 2001 and 2016, of over 71 billion US dollars in commitments – and slightly over 61 billion US dollars in actual disbursements, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (see dataset here). The main donors were the US, UK, EU, Japan, Germany, the Nordic countries, Australia and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

Kabul-based financial experts who prefered to remain anonymous estimate that the country received more than double that amount in military support over the same period; the exact figure is not in the public domain. (7) Recent figures on US spending alone seem to confirm this ratio. According to a 2018 report entitled “Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy In Brief”:

… Congress has appropriated more than $126 billion in aid for Afghanistan since [financial year] 2002, with about 63% for security and 28% for development (and the remainder for civilian operations, mostly budgetary assistance, and humanitarian aid).

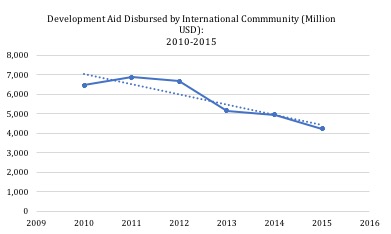

But aid levels to Afghanistan have fluctuated since 2001. After years of a slow rise, the aid total peaked in 2011, only to decrease significantly afterwards (see here). According to the Oxfam/SCA report, Afghanistan received 6.867 billion USD in 2011, compared to 4.239 billion in 2015(see figure 1 below). The World Bank estimated a decline from an annual average of 12.5 billion USD between 2009 and 2012 to around 8.8 billion USD in 2015. As indicated in this dispatch, records on development aid for Afghanistan vary from source to source.

The Oxfam/SCA report also pointed out discrepancies in the reported amounts of development aid for Afghanistan:

In its report, the Ministry of Finance states that Afghanistan received a total of USD 12.9 billion in development assistance in the period 2012-2014, which is less than a figure of 16.8 USD billion reported by the World Bank for the same period. […] The challenge to obtain accurate data on how much development aid has been received from 2010-2106 points to a lack of transparency and coordination within the aid sector of Afghanistan where clear financial data is not readily available, and agreed upon.

The report, in addition, highlights that aid disbursements have been far lower than the pledges. But this is hardly news, as the same finding came out of the 2008 Oxfam report, which said that “donors are far quicker to make promises than to report on disbursements and shortfalls.” In the period 2002 to 2008, out of 25 billion USD committed, Afghanistan actually received less than two-thirds, or around 15 billion USD for development and reconstruction, the 2008 report found. (In the same period Afghanistan received an additional 5 billion USD for the government.)

The new joint Oxfam/SCA report, however, says that there has been some improvement in the ratio between commitment and disbursement. According to the Afghan Government’s Central Statistics Organisation (AGCSO) data, the report noted “the international community has been improving since 2009/10 when only 31 per cent of pledged funding was disbursed, to 2016/17 when 71 per cent of what it had pledged was disbursed.” This point was also reiterated in an earlier International Crisis Group report, which said that between 2001 and 2011, 57 billion dollars of aid money had been spent in Afghanistan against 90 billion pledged (see this AAN analysis).

Changed aid paradigm: Development now for development’s sake?

Another factor that has influenced aid fluctuations is that ten years after the 2008 Oxfam report, the donor landscape in Afghanistan as well as the dominant development paradigm has changed. Some of the major aid actors, ie the international military, which distributed the lion’s share of development and humanitarian aid through its Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs), have almost completely disappeared. The PRT Commanders Emergency Response Program (CERP) set up by the US, for example, spent about 1.5 billion USD alone between 2004 and 2011. But this high spending contributed little to the desired outcome of stabilisation, which had been the dominant development paradigm up until then.

As noted in 2009 by Andrew Wilder, “given the centrality to the counterinsurgency (COIN) strategy of the assumption that aid is an important stabilization tool, and the billions of development dollars allocated based on this assumption, there is surprisingly limited evidence from Afghanistan that supports it.” Wilder also noted that despite the amount of money spent, “Afghan perceptions of aid and aid actors had been overwhelmingly negative” (see also this Tufts University study on PRT in Helmand here). In contrast to the 2008 Oxfam recommendation to increase development aid to Afghanistan at the expense of military support, donor support to development and humanitarian needs has decreased over the years.

Aid dependency still high

Afghanistan’s aid dependency rate, meanwhile, remained extremely high. Between 2005 and 2011, it averaged 76 per cent of the country’s GDP (see here). This means that over that period Afghanistan’s aid dependency was more than three times higher than the rule of thumb proposed for optimal aid levels for a functioning, sovereign state by the Washington-based Institute for State Effectiveness, at around 20 per cent of GDP (see here). According to the World Bank, this rate decreased to 45 per cent in 2017, still more than double the recommended rate.

In short, the country has been swamped with money since 2001, which has driven its heavy dependence on development aid to new levels. Between 1977 (the last full year of the Republic) and 1988 (the last full year of Soviet troop presence), foreign (mainly Soviet) aid roughly covered between one fourth and one third of state expenditures, according to a 2007 Canadian study (see here).

Rising poverty as a key outcome?

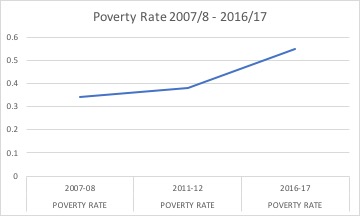

Another trend becomes apparent when reading the Oxfam/SCA report and the Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey released on 2 May 2018 by the Central Statistics Organization (CSO) in cooperation with the Afghan Ministry of Economy and the World Bank (see here): that the large amounts of aid disbursed since 2001 have not reduced poverty in Afghanistan. This is nothing but a result of continuing ineffectiveness. While the rate of Afghans living in poverty was lowered from the 2003 World Bank’s baseline of 51.4 per cent of the population in 2003 – ie during the immediate post-Taleban era, when aid flows were still moderate – (see here) to around 34 per cent in 2007/08, these gains were subsequently lost again. The paradigm shift around 2011 – which should have been in the right direction, making development the paradigm instead of stabilisation – was accompanied by a slump in aid money alongside the gradual withdrawal of foreign troops, the transition (‘handover of responsibility’) and the Afghan government’s paradigm of going from transition to ‘transformation’. This seems to have resulted in a higher poverty rate, once again. It increased to around 38 per cent in 2011/12, which was, until recently, the last official CSO figure (see here). (8) It is now 54.5 per cent. In fact, this is even higher than the 2003 figure in the immediate post-Taleban period. During the Taleban regime, international aid was as low as 564 million USD for the entire period between 1995 and 2000, according to the OECD data set already quoted above. This, combined with the non-policies of the Taleban, led to widespread impoverishment.

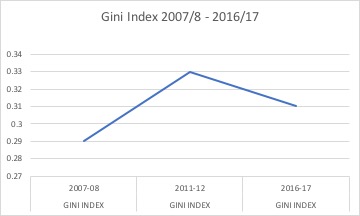

In 2015, the Afghan Ministry of Economy explained the lack of poverty reduction in spite of growing development assistance in its Afghanistan Poverty Status Update by an increase in inequality, measured by the Gini index. (9) According to the document, this index in Afghanistan increased from 29.7 per cent in 2007/08 to 31.6 in 2011/12, when the country received the highest amount of development aid (see figures 2 and 3). It stated, “Had Afghanistan’s economic growth been more widely shared, poverty could have declined by as much as 4.4 percentage points.” That the Gini index had decreased by 2016/17 (despite an increase in poverty) does not mean, however, that growth was being shared more widely or more equally. It is a statistical phenomenon resulting from an almost 20 per cent increase in the poverty rate.

A possible way forward

It is expected that at the Geneva donor conference in November this year, the 2016 Brussels conference commitments will go through a mid-term review. It also means that a new set of indicators and targets could be designed to measure Afghanistan’s progress towards self-reliance. At the same time the question remains open as to who will measure how donors align themselves with the 2005 Paris Declaration and how they will deliver on their financial promises. The non-governmental Oxfam/SCA report may be a good example of an exercise in self-scrutiny, but there is still a lot to be done by other actors, too, particularly among governments. Part of the problem concerns Afghanistan’s chronic corruption and points to a lack of statesmanship among the country’s political élite. They see power as a way of accessing ‘rent-seeking’ while proving unable to address the large and rising portion of their fellow Afghans languishing in poverty. This requires a behavioural change on their part. But an equally radical change is probably required by donors, who need to review their way of doing business in Afghanistan, in line with some of the recommendations made by the recent reports on aid effectiveness.

By Special Arrangement with AAN. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.