President Trump’s advisers recruited two businessmen who profited from military contracting to devise alternatives to the Pentagon’s plan to send thousands of additional troops to Afghanistan, reflecting the Trump administration’s struggle to define its strategy for dealing with a war now 16 years old.

Erik D. Prince, a founder of the private security firm Blackwater Worldwide, and Stephen A. Feinberg, a billionaire financier who owns the giant military contractor DynCorp International, have developed proposals to rely on contractors instead of American troops in Afghanistan at the behest of Stephen K. Bannon, Mr. Trump’s chief strategist, and Jared Kushner, his senior adviser and son-in-law, according to people briefed on the conversations.

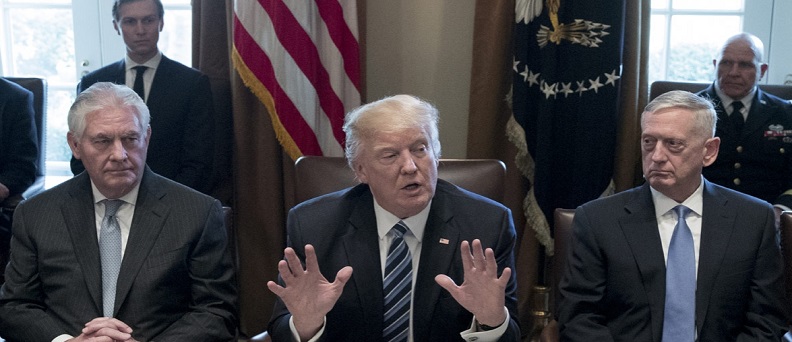

On Saturday morning, Mr. Bannon sought out Defense Secretary Jim Mattis at the Pentagon to try to get a hearing for their ideas, an American official said. Mr. Mattis listened politely but declined to include the outside strategies in a review of Afghanistan policy that he is leading along with the national security adviser, Lt. Gen. H. R. McMaster.

The highly unusual meeting dramatizes the divide between Mr. Trump’s generals and his political staff over Afghanistan, the lengths to which his aides will go to give their boss more options for dealing with it and the readiness of this White House to turn to business people for help with diplomatic and military problems.

Soliciting the views of Mr. Prince and Mr. Feinberg certainly qualifies as out-of-the-box thinking in a process dominated by military leaders in the Pentagon and the National Security Council. But it also raises a host of ethical issues, not least that both men could profit from their recommendations.

“The conflict of interest in this is transparent,” said Sean McFate, a professor at Georgetown University who wrote a book about the growth of private armies, “The Modern Mercenary.” “Most of these contractors are not even American, so there is also a lot of moral hazard.”

Last month, Mr. Trump gave the Pentagon authority to send more American troops to Afghanistan — a number believed to be about 4,000 — as a stopgap measure to stabilize the security situation there. But as the administration grapples with a longer-term strategy, Mr. Trump’s aides have expressed concern that he will be locked into policies that failed under the past two presidents.

Mr. Feinberg, whose name had previously been floated to conduct a review of the nation’s intelligence agencies, met with the president on Afghanistan, according to an official, while Mr. Prince briefed several White House officials, including General McMaster, said a second person.

Mr. Prince laid out his views in an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal in May. He called on the White House to appoint a viceroy to oversee the country and to use “private military units” to fill the gaps left by departed American soldiers. While he was at Blackwater, the company became involved in one of the most notorious episodes of the Iraq war, when its employees opened fire in a Baghdad square, killing 17 civilians.

After selling his stake in Blackwater in 2010, Mr. Prince mustered an army-for-hire for the United Arab Emirates. He has cultivated close ties to the Trump administration; his sister, Betsy DeVos, is Mr. Trump’s education secretary.

If Mr. Trump opted to use more contractors and fewer troops, it could also enrich DynCorp, which has already been paid $2.5 billion by the State Department for its work in the country, mainly training the Afghan police force. Mr. Feinberg controls DynCorp through Cerberus Capital Management, a firm he co-founded in 1992.

Mr. McFate, who used to work for DynCorp in Africa, said it could train and equip the Afghan Army, a costly, sometimes dangerous mission now handled by the American military. “The appeal to that,” he said, “is you limit your boots on the ground and you limit your casualties.” Some officials noted that under the government’s conflict-of-interest rules, DynCorp would not get a master contract to run operations in Afghanistan.

A spokesman for Mr. Feinberg declined to comment for this article, and a spokesman for Mr. Prince did not respond to a request for comment.

The proposals Mr. Prince presented, a former American official said, hew closely to the views outlined in his Journal column — in essence, that the private sector can operate “cheaper and better than the military” in Afghanistan.

Mr. Feinberg, another official said, puts more emphasis than Mr. Prince on working with Afghanistan’s central government. But his strategy would also give the C.I.A. control over operations in Afghanistan, which would be carried out by paramilitary units and hence subject to less oversight than the military, according to a person briefed on it.

The strategy has been called “the Laos option,” after America’s shadowy involvement in Laos during the war in neighboring Vietnam. C.I.A. contractors trained Laotian soldiers to fight Communist insurgents and their North Vietnamese allies until 1975, leaving the country under Communist control and with a deadly legacy of unexploded bombs. In Afghanistan until now, contractors have been used mainly for security and logistics.

Whatever the flaws in these approaches — and there are many, according to diplomats and military experts — some former officials said it made sense to open up the debate.

“The status quo is clearly not working,” said Laurel Miller, who just stepped down as the State Department’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan. “If the United States is going to chart a way forward towards a sustainable way of protecting our national security interests, it is important to consider a wide range of options.”

Despite Mr. Bannon’s apparent inability to persuade Mr. Mattis, Defense Department officials said they did not underestimate his influence as a link to, and an advocate for, Mr. Trump’s populist political base. Mr. Bannon has told colleagues that sending more troops to Afghanistan is a slippery slope to the nation building that Mr. Trump ran against during the campaign.

Mr. Bannon has also questioned what the United States has gotten for the $850 billion in nonmilitary spending it has poured into the country, noting that Afghanistan confounded the neoconservatives in the George W. Bush administration and the progressives in the Obama administration.

Mr. Kushner has not staked out as strong a position, one official said. But he, too, is sharply critical of the Bush and Obama strategies, and has said he views his role as making sure the president has credible options. Mr. Mattis has promised to present Mr. Trump with a recommendation for a broader strategy this month.

Like General McMaster, Mr. Mattis is believed to support sending several thousand more American troops to bolster the effort to advise and assist Afghan forces as they seek to reverse gains made by the Taliban. But he has been extremely careful in his public statements not to tip his hand, and has not yet exercised his authority to deploy troops.

Aides and associates say that while Mr. Mattis believes that Mr. Prince’s concept of relying on private armies in Afghanistan goes too far, he supported using contractors for limited, specific tasks when he was the four-star commander of the Pentagon’s Central Command.

“No one should diminish the role that they play,” Mr. Mattis, then a general, told the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 2012. “It is expensive, but there are places and times where having a contract force works well for us, as opposed to putting uniformed military to do, whether it’s a training mission or a security guard mission.”

The Pentagon has developed options to send 3,000 to 5,000 more American troops, including hundreds of Special Operations forces, with a consensus settling on about 4,000 additional troops. NATO countries would contribute a few thousand additional forces.

“It seems likely that the new strategy in Afghanistan will look a lot like what was proposed at the end of 2013,” said James G. Stavridis, a retired admiral who served as NATO’s top military commander.

Some critics say the increase will have little effect on the fighting on the ground. In May, Dan Coats, the director of national intelligence, testified that the situation in Afghanistan would probably deteriorate through 2018 despite a modest increase in American and NATO forces.

Asked in June by reporters in Brussels about that analysis, Mr. Mattis responded curtly, “They’re entitled to their assessment.”

This article originally appeared on www.nytimes.com, July 10, 2017. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in the article are not necessarily supported by Afghan Studies Center.