November 03, 2018

Zurmat district in Paktia province is almost completely under Taleban control. The parliamentary elections were held there only on a tiny island of government control. Turnout was very low on the first election day and limited to the district centre – another example of Afghanistan’s emerging rural-urban voting divide. On day two, attempts of ballot stuffing were observed, when the election commission had allowed to open polling centres that were closed or opened very late on the first election day.

The security situation in Zurmat

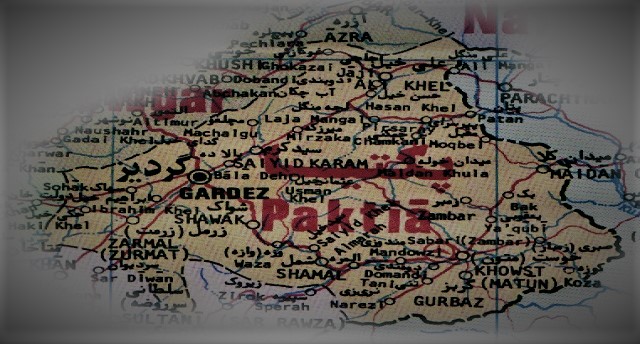

Zurmat district is the southwestern most district of Paktia, bordering Paktika in the south, Ghazni in the west and located direct to the southwest of the provincial capital Gardez. The district is the Taleban’s main regional stronghold and the most war-affected district of the province. Tamir, the district centre, is the only area in the district where there is still some government presence. There is a local Afghan National Army (ANA) base, some Afghan National Police (ANP) and some fighters left from a dissolved local Afghan Local Police unit. (The ALP unit was dissolved earlier this year at the request of the local community after some of its members attacked a school girl and robbed the house of a teacher, killing him in the event.) The local government officials live closely together in one particular area of town, called Khwajagan village, near the ANA base, in order to be able to defend themselves.

Zurmat’s security was reinforced in late August 2018 by a “strike unit” (quwa-ye zarbati) that, local sources say, works closely “with the Americans” (possibly the CIA-led Khost Protection Force). The new unit’s main focus is to secure the road between Gardez and Zurmat, where it has taken over the existing ANP check posts. The unit seems to operate out of Khost, and has no base in Tamir.

The areas outside Tamir are under firm Taleban control. A second ANA base in Sahak is encircled and does not carry out any operations. The road leading there from Tamir is heavily mined and unusable for civilian traffic.

For historical reasons, Zurmat is sometimes called Little Kandahar, as a number of prominent Taleban leaders came from the area. For Greater Paktia – the three provinces of Paktia, Paktika and Khost – Zurmat was as important for the insurgents, as Kandahar was for southern Afghanistan (see this background paper).

Two different networks of the Taleban are active in the area: the Haqqani network, led by Qari Shams, and the Mansur network, locally called the ‘Mansurian’ – led by Abdul Latif Mansur, a member of the Taleban leadership and relative of the network’s founder, the late Nasrullah Mansur (for more background, see this AAN paper). They are rivals and keep separate structures, sometimes clashing among themselves, at other times carrying out joint operations. Both were unanimous in their rejection of the elections. They forced local teachers, who were being mobilised all over the country as the principal elections workers, to hand over their tazkeras – both to prevent them from voting and to scare them away from working with the government. The teachers were told they would get their documents back after the elections. (Outside Tamir, the Taleban also keep track of teachers’ school attendance and fine them for absences, in an effort to take control of the local education system.) The teachers, apart from some areas closer to the Gardez-Zurmat road, could do little about it and complied. As a result, very few teachers worked in the few polling centres that did open in Zurmat.

The run-up to the election in Zurmat: Registration, campaigning and threats

Zurmat’s population is estimated at 95,000 by Afghanistan’s Central Statistics Office (see here, p18), not counting the 22,000 people in Rohani Baba district that was recently separated from Zurmat. According to the Independent Election Commission (IEC), over one third – 33,320 people – registered as voters between May and July 2018; 28,408 of them men, 4,031 women and another 881 Kuchis (who were not specified with regard to gender). The IEC claims that all 22 voter registration centres in Zurmat district – that were supposed to double as polling sites on 20 October – were open during the voter registration period. Local observers told AAN, however, this was not the case; the commission’s claims also sound implausible given the almost total Taleban control outside the district centre.

In the run-up to the elections, there were constant warnings by the insurgents not to participate in the polls. Leaflets – so called shabnama(night letters) – were posted in the schools and mosques of Tamir and other villages. Outside Tamir, the Taleban directly addressed mosque congregations and spread their message over mosque loudspeakers. Ahead of election day, no election staff or electoral material was transferred to any of the 19 polling centres outside Tamir, for security reasons. As a result, many people in Zurmat did not expect that the elections would be held in their area.

This was cause for concern, as many people were already unhappy that Zurmat did not have a representative in the previous parliament. This meant that they had no one to raise their problems with in Kabul. These problems ranged from the long-pending, still-unpaved Gardez-Zurmat road, to the provincial and district administration officials who were keeping them waiting with false promises, and, further, the prisoner issues that plague many inhabitants in the district (as a result of Zurmat’s strong insurgency, many local people have relatives who have been – rightly or wrongfully – detained; it is often very difficult to find out where they are without someone speaking for them in the county’s capital).

The election-related awareness campaign was relatively weak and late. People in Zurmat were reached mainly through the airwaves. With mobile phones and radios widely available, the Taleban was unable to control radio broadcasting and people were able to hear some election-related information. There was also some limited campaigning by candidates, including campaign posters, in the district’s centre of Tamir. Some candidates had used the June ceasefire which overlapped the voter registration campaign – long before the official start of the campaign – to gather people in the district governor’s compound and the new hospital that was inaugurated in during Ramazan in May-June. Young voters, in particular, seemed eager to register to vote at that time.

Several candidates were said to have distributed cash money, including US dollars, during the campaign, according to AAN sources with families in the area. Others “bought up” tazkeras, to be used for potential ballot stuffing or proxy voting, and/or to prevent people from promising and casting their vote for rival candidates. (In some cases, copies of tazkeras were taken or names and ID numbers were noted; in other cases, candidates kept the original tazkeras.) Village elders would often organise the “selling” of the tazkeras and send these people to certain candidates. The price was reportedly 2,000 Pakistani rupees (around 15 US dollars) per document.

Zurmat has a number of local candidates on the ballot, vying to represent the district in Kabul. The most prominent ones are Dr Usman, a medical doctor from Zurmat who lives in Kabul, and Sharifa Zurmati, a female candidate. She was a member of the first post-Taleban parliament in 2005, became an advisor to both presidents Hamed Karzai and Ashraf Ghani, and was also an IEC commissioner in the 2014 presidential election.

Polling in the first day of the election (20 October 2018)

Election Day in Paktia province started with some small arms fire in areas near Gardez, the provincial capital, presumably to scare off possible voters. Still, people in the city turned out in large numbers, as well as in parts of some districts. On the road to Zurmat’s district centre, Tamir, this scenery already changed just a few kilometres outside the city. The town is only some 40 minutes from Gardez by car. The road leading there is asphalted but in disrepair, due to years of insecurity. In Ibrahimkhel, for instance, a village with one polling centre that administratively still belongs to the provincial capital, there was sporadic firing all day. The polling centre in the village’s school was kept open during the day, but very few people came, mainly from nearby houses.

In Zurmat, 19 of the 22 scheduled polling centres remained closed. The only three polling centres that were open were in Tamir: two high schools directly in the bazaar, Habibullah Lycee and Bator Lycee, and a centre in Muqarabkhel, a short distance outside town on the road to Ibrahimkhel and Gardez. The Taleban had mined several other access roads to Tamir, and did not even allow the bazaar’s shopkeepers who live outside of town to enter. Taliban fighters were sitting in the poplar trees along the roads leading to Tamir, occasionally firing at the city. The Afghan army occasionally fired back. There seem to have been no casualties.

Voting in Tamir’s three open polling centres started around 9:30am, with only a few people coming out at first. People were wary of the security situation and wanted to see if others would be able to come out and vote without trouble. Meanwhile, the Taleban fired missiles at the district centre throughout the day (according to ocal election observers possibly as many as 50 or 60). They hit three shops, wounding one person, as well as several civilian houses, killing two children. There were also some gunshots fired in the air – but some local people thought this was the district police chief’s work, saying he was trying to scare away voters, so that only the supporters of the candidate he was rumoured to support would be able to cast their votes.

The rocket fire died down at around 2pm, so in the afternoon, more people dared to come out and vote, even from nearby villages. The three polling stations were kept open one hour longer than planned, till 5pm, and then counting started.

There were no observers from independent organisations present at the Zurmat polls, but a few dozen candidates’ agents, mainly representing candidates who expected a significant number of votes from that polling centre. During the day, there were scuffles between them. The district police chief also had some candidate agents thrown out of a polling station, reportedly because he opposed their candidates. Some candidate agents alleged that the Paktia IEC team was not neutral and that IEC members had told certain candidates that they did not have enough votes. Presumably, the candidate agents thought this indicated the IEC member’s readiness to accept money to manipulate the vote in their favour.

Although, there had been some problems with the biometric verification in Gardez – the IEC staff had not been well trained and only two devices had been used all day in the city’s main polling centre, the Gardezi high school – the devices were apparently used all day in Zurmat without major problems. As in other places, some voters in Zurmat could not find their names on the voter lists. Polling staff then opened provisional lists.

Overall turnout in Zurmat was low because of fighting and security threats. Based on observations, the author estimates that a total of around 500 votes were cast in the three polling centres in Zurmat. (1). The voters who came appeared to mainly be locally deployed soldiers, police and arbaki, the district’s administrative staff, and shopkeepers from the nearby bazaar as well as staff from the district hospital. No women were seen to vote in Zurmat. How could they – it was difficult even for men to vote.

At the end of the day, the ballot boxes and other electoral material were transported to Gardez. Although the Taleban fired at the returning convoy, they did not attack it directly and the boxes reached the IEC’s provincial office unharmed. However, before that happened, candidate agents told AAN they believed ballot stuffing took place in Tamir’s Habibullah high school, after the official closure at 5pm (till about 9pm). At the end of the day, around 2,000 votes were sent to the provincial capital from this centre. If this did occur, it should be easy to track, as, reportedly, biometric voter verification had been used there during the day.

Rohani Baba, a district on paper

Rohani Baba was formerly a part of Zurmat and is one of several new “temporary” (ie not yet fully functional) districts that have been established countrywide. It has a district governor – Abdul Rahman Solamal, who previously had the same position in Janikhel – but no official district administrative centre (DAC) yet. He is from Zurmat centre and resides there. The establishment of the district centre has been complicated by tribal disputes, mainly between the local Sahak and Mamozai tribes, regarding where the DAC should be located. (The contest over who might ‘win’ the DAC indicates that local tribes might welcome some more government presence in their area, which so far has been Taleban-controlled.) Property prices in the area have already gone up in anticipation of the changes, but so far little has happened. The district, for now, only exists on paper.

During the voter registration campaign, inhabitants from Rohani Baba came to Tamir in Zurmat to register – but under the name of the new temporary district, as the voter list published by the IEC shows. A total of 11,237 voters from Rohani Baba registered, 1844 of them were women. Local sources told AAN that there had been irregularities. Village elders reportedly came with hundreds of tazkeras that were registered and given stickers, even though their owners were not present.

The IEC had listed nine polling centres for Rohani Baba, but none of them opened. It was even unclear whether they ever really existed.

Polling in the second day of the election (21 October 2018)

On 20 October 2018, the (IEC) announced that the polling centres in Zurmat and neighbouring Rohani Baba districts which had remained closed that day, would be opened the next day – as part of a countrywide extra day of voting for polling centres that had opened late or did not open at all (see AAN reporting). An IEC list, seen by AAN, of the 410 polling stations countrywide that were supposed to open on the second day of voting, contained all 19 polling centres from Zurmat that had remained closed on 20 October but only six (out of nine) in Rohani Baba. Three sites in Rohani Baba – two in a mosque and one in a madrassa – were missing. (AAN has reported earlier that the IEC figures and lists have often been inconsistent.)

Fears of ballot-stuffing on day two

People in Zurmat wondered how the security forces had suddenly became capable of securing these polling centres outside Tamir in one day, even though they had been unable to secure the vote in Ibrahimkhel, which was much closer to the provincial capital.

They were concerned that claims of polling sites opening in such remote unsecured areas might be used for electoral fraud, mainly for ballot stuffing, as during previous elections (AAN reports from Paktia’s 2010 elections here and here). Local election observerstold AAN that some local candidates had indeed persuaded the local IEC administration to – on paper – open between three and five centres in Zurmat, outside Tamir, (reports on numbers differed) and at least one in Rohani Baba, in Neknam village. According to the various observers AAN spoke to, there had been no actual voting at all at these sites but there was ballot stuffing on-going in private houses. It was not clear how the electoral material had reached there. Observers told AAN that the IEC has quarantined the boxes from Neknam village with circa 400 votes, but it was not clear whether boxes including the additional votes from Zurmat have also been quarantined.

Conclusion: Only islands of voting

The general trend of an emerging rural-urban divide in voting turnout, which AAN reported after election day one on 20 October, has been confirmed in both Zurmat district and the neighbouring, Rohani Baba district. Zurmat – a district where the centre is under government control and was accessible for election workers and materiel as well as for observers – while the countryside is controlled by the Taleban with no access for voters is further proof that this divide exists not only on the provincial, but also on the district level.

The insular government presence in Zurmat centre allowed some voting, but the Taleban’s intimidation potential led to a very low level of turnout even there. It represents less than two per cent of the number of voters the IEC said had registered. Registration figures might have been doctored, but also many voters who might have genuinely registered in spring may not have gone out once the Taleban renewed their call for an election boycott on 8 October, after attempts to arrange a ceasefire covering the elections failed.

Difficult or impossible access to Zurmat and Rohani Baba also made attempts of ballot stuffing possible in rural polling centres that were on the IEC list but never opened in reality (very likely also not during voter registration), as observers’ reports showed. These reports also showed that some of those fake votes were detected and quarantined, but it is doubtful that all those ballots will be identified and cancelled – particularly as it seems that genuine ballots cast in polling centres in Zurmat’s district capital might have been topped up with night-time ballot stuffing. In this, the lack of independent observers in contested areas is a major downside.

By Special Arrangement with AAN. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed on this blog are not necessarily endorsed or supported by the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad.